Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site BX012X02C022

Loamy 15 to 19 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains

Last updated: 5/07/2025

Accessed: 05/19/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 012X–Lost River Valleys and Mountains

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 012X, Lost River Valleys and Mountains, consists of approximately 4.85 million acres in Idaho. MLRA 012X is broken into two Land Resource Units (LRU) based on geology, landscape, common soils, water resources, and plant community potentials. The elevation ranges from approximately 3,600 feet (1,100 meters) in the valleys and extends to the highest point in Idaho, Mt. Borah, at 12,662 feet (3,869 meters). Annual precipitation has a significant range from six to 47 inches, the driest areas in the valley bottoms and the wettest areas on the mountain summits. This MLRA encompasses portions of the Salmon-Challis National Forest, small amounts of private land, as well as other public land managed by the State of Idaho and the Bureau of Land Management. The Continental Divide runs through the Beaverhead Mountain Range directly east of the MLRA and adjacent forests and parks include the Beaverhead National Forest, Custer Gallatin National Forest, Caribou-Targhee National Forest, and Craters of the Moon National Park.

LRU notes

The Lost River Mountain LRU is located on the Lemhi, Lost River, and White Knob Mountain Ranges. These mountain ranges extend from Salmon, Idaho to the north, Craters of the Moon National Monument to the south, the Beaverhead Mountain Range to the east, and the Sawtooth Mountains to the west. This LRU borders MLRA 043B - Central Rocky Mountains, and a small portion of MLRA 010X - Central Rocky Mountains and Foothills.

The geology of this LRU is comprised mostly of colluvium from the Challis Volcanic Group, limestone from the Permian to Mississippian Period, and till from Pleistocene glacial deposits. Additionally, metasedimentary formations from the Proterozoic dominate the Lemhi Range. The elevation range of this LRU is similar to that of the MLRA (approximately 4,000 to 12,500 feet). The boundary of the unit begins where the three mountain ranges meet the valley floor and extends to the mountain peaks. Effective precipitation (estimate of the moisture available for plant use and soil forming processes at a given site) generally ranges between 10 to greater than 36 inches. The soil temperature regimes present are frigid and cryic, and the soil moisture regimes include xeric and udic. The soils for the LRU are dominated by mollisols and inceptisols from limestone and quartzite parent material, as well as glacial till.

Classification relationships

Relationship to Other Established Classification Systems

National Vegetation Classification System (NVC):

3 Semi-Desert

3.B.1 Cool Semi-Desert Scrub & Grassland

3.B.1.Ne Western North American Cool Semi-Desert Scrub & Grassland Division

M169 Great Basin-Intermountain Tall Sagebrush Steppe & Shrubland Macrogroup

G304 Intermountain Mountain Big Sagebrush Steppe & Shrubland Group

A3208 Mountain Big Sagebrush Steppe & Shrubland

Ecoregions (EPA):

Level I: 10 Northwestern Forested Mountains

Level II: 10.1 Western Cordillera

Level III: 10.1.4 Middle Rockies

Ecological site concept

This site does not receive additional water and occurs on slopes of less than 30 percent.

These soils:

o Are not saline, saline-sodic, or sodic

o Are not highly calcareous within the top 50 centimeters.

o Are moderately deep, deep, or very deep

o Consist of fine sandy loam to clay loam textures (includes silt loams, loams, and sandy clay loams)

o Are highly productive

The primary resource limitation for this ecological site is relative effective annual precipitation. This site is not impacted by soil depth, soil chemistry, slope steepness, or high volumes of course fragments within the soil profile.

Associated sites

| BX012X02C070 |

Steep Loamy 15-19 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains Transition to this site occurs as slope steepness increases, exceeding 35 percent. |

|---|---|

| BX012X02C068 |

Skeletal 15-19 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains Transition to this site can occur as coarse fragment volume in the top 50cm averages greater than 35 percent. |

| BX012X02B026 |

Loamy Calcareous 10-14 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains This site can be adjacent and contain similar plant communities, however, soils are highly calcareous in the 25-50cm range. |

| BX012X02C034 |

Rocky Hills 15-19 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains This site can occur adjacent or interspersed where localized areas of bedrock are closer to the surface. |

Similar sites

| BX012X02C070 |

Steep Loamy 15-19 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains This site is similar in soil composition and structure but only occurs on slopes >30%. |

|---|---|

| R012XY021ID |

Loamy 16-22 PZ ARTRV/FEID This is a provisional ecological site, covering the Lost River Valley LRU. |

| BX012X02C026 |

Loamy, Calcareous 15-19 Inch Precipitation Zone Lost River Mountains This site is similar in soil composition and structure, however, has a highly calcareous subsoil (>15% CCE) between 25 and 50cm which influences plant community composition and decreases plant production. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Festuca idahoensis |

Legacy ID

R012XC022ID

Physiographic features

This site can occur on mountain slope, alluvial fans, drainageways, stream terraces, and glacial valley walls, within the mountain landscape. The site is not aspect-dependent, though aspect may influence the elevation at which it occurs. Additionally, this site is not influenced by slope percentage, however occurs on slopes ranging from 15 to 65 percent. Runoff is generally low to moderate and flooding and ponding do not occur.

Landscape Definition:

Mountains -- A region or landscape characterized by mountains and their intervening valleys.

Landform Definition:

Mountain Slope -- A part of a mountain between the summit and the foot.

Alluvial Fan -- A low, outspread mass of loose materials and/or rock material, commonly with gentle slopes, shaped like an open fan or a segment of a cone, deposited by a stream (best expressed in semiarid regions) at the place where it issues from a narrow mountain or upland valley; or where a tributary stream is near or at its junction with the main stream.

Drainageway -- A general term for a course or channel along which water moves in draining an area.

Stream Terrace - One, or a stepped series of flat-topped landforms of alluvium in a stream valley, that flank and are parallel to the stream channel.

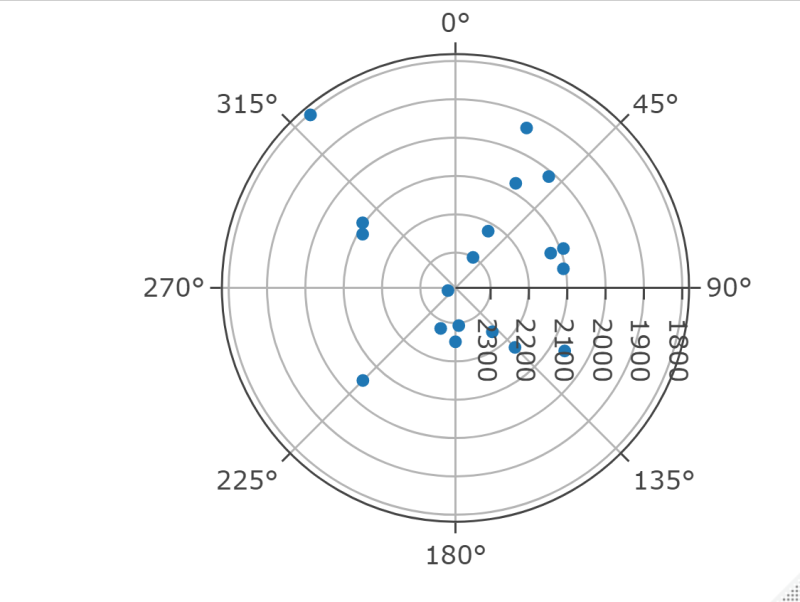

Figure 1. Plot showing aspect (degrees) and elevation (meters) of each Shallow to Loamy 15-19" range site surveyed in the Lost River Mountain LRU

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountains

> Mountain slope

(2) Mountains > Drainageway (3) Mountains > Alluvial fan (4) Mountains > Stream terrace |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to medium |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 6,602 – 7,475 ft |

| Slope | 11 – 25% |

| Aspect | W, NW, N, NE, E, SE, S, SW |

Table 3. Representative physiographic features (actual ranges)

| Runoff class | Negligible to medium |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 6,120 – 7,662 ft |

| Slope | 5 – 28% |

Climatic features

In the Lost River Mountain LRU, both precipitation and temperatures fluctuate significantly throughout the seasons and year to year. Relative effective annual precipitation (estimate of the moisture available for plant use and soil forming processes at a given site) generally ranges between 10 to greater than 36 inches. Average daily temperatures during the growing season (April to August) range from 33 to 57 degrees Fahrenheit. These wide fluctuations in temperature and precipitation are largely due to elevation and aspect differences as well as lower relative humidities and drier air in the mountainous terrain of the LRU. The wettest months in terms of rainfall are May and June. The growing season varies across the LRU in relation to topographical and local conditions; however, generally ranges between 30 to 90 days. Most primary growth occurs from late April through June. Soil temperature regimes include cryic and frigid and soil moisture regimes include xeric and udic.

For this ecological site, the effective precipitation is 15 to 19 inches. Because effective precipitation is a modeled value that factors in elevation, aspect, and topography in association with mean annual precipitation, it is often a lower value than actual precipitation. Actual precipitation and temperature data were taken from Snotel stations located on the Lost River and Lemhi Range. Data was taken from Snotel sites that record actual precipitation and sit at a fixed location. Therefore, actual climatic conditions at a given ecological site can vary from data provided based on localized conditions.

Table 4. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 30-60 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 40-65 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 18-27 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 25-75 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 40-85 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 14-31 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 45 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 60 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 21 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Influencing water features

This is an upland ecological site and is not influenced by additional water beyond the precipitation the site receives.

Wetland description

This ecological site is not associated with wetlands.

Soil features

The soils of this site are moderately deep to very deep, ranging from 20 to greater than 60 inches (50 to 150 centimeters) and consist of textures ranging from fine sandy loams to clay loams. Soils are not skeletal (greater than 35 percent coarse fragments) and are formed from slope alluvium, colluvium and alluvium derived from varying parent materials including but not limited to andesite, rhyolite, volcanic rock, and sandstone. Soils are not highly influenced by carbonates in the top 20 inches (50 centimeters), and the soils are well drained.

Soil taxonomy that fits the core concept of the Loamy 15-19 inch site include:

Fine-loamy, mixed, superactive Pachic Argicryolls

Fine-loamy, mixed, superactive, frigid Typic Argixerolls

Soil taxonomy that fits the range of variability of the Loamy 15-19 inch site include:

Fine-loamy, mixed, superactive Xerollic Haplocryalfs

Fine-loamy, mixed, superactive, frigid Mollic Haploxeralfs

Loamy-skeletal, mixed, superactive Typic Argicryolls

Loamy-skeletal, mixed, superactive, frigid Typic Argixerolls

Clayey-skeletal, mixed, superactive Xerollic Haplocryalfs

Figure 8. Soil profile for site 2019ID7031079.

Figure 9. Sample of 10 Loamy 15-19" Ecological Site Soil Horizon Textures

Table 5. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Colluvium

–

volcanic rock

(2) Colluvium – andesite (3) Colluvium – rhyolite (4) Slope alluvium – volcanic rock (5) Slope alluvium – andesite (6) Slope alluvium – rhyolite (7) Alluvium |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam (2) Clay loam (3) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Fine-loamy (2) Loamy-skeletal |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate |

| Soil depth | 40 – 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 7% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 2% |

| Available water capacity (0-20in) |

3 – 3.8 in |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-20in) |

6.2 – 6.7 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-20in) |

5 – 16% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-20in) |

2% |

Table 6. Representative soil features (actual values)

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to well drained |

|---|---|

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderately rapid |

| Soil depth | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 10% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 2% |

| Available water capacity (0-20in) |

2.3 – 3.9 in |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-20in) |

5.8 – 7 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-20in) |

22% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-20in) |

14% |

Ecological dynamics

The Loamy 15 - 19 Inch Precipitation Zone ecological site is dominated by a mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana) overstory and a bunchgrass understory. The ecological site exists in two states, a reference state and a disturbed state. Under the umbrella of those two states, five different plant communities exist. Transitions between states and communities are primarily driven by natural disturbance regimes, the most significant being grazing that results in chronic defoliation (both natural and agricultural) and fire at relatively frequent fire return intervals.

A state-and-transition model (STM) diagram for this ecological site is depicted in this section. Thorough descriptions of each state, transition, plant community phase, and pathway are found after the state-and-transition model. This STM is based on available experimental research, field observations, professional consensus, and interpretations. While based on the best available information, the STM will change over time as knowledge of ecological processes increases.

Plant community composition within this ecological site has a natural range of variability across the LRU due to the natural variability in weather, soils, and aspect. The reference plant community may not fit management goals. Selection of other plant communities is valid if the identified range health attributes have none to slight or slight departures from the Reference state. The biological processes on this site are complex; therefore, representative values are presented in a land management context. The species lists are representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species potentially occurring on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the ecological site.

Both percent species composition by weight and percent cover are used in this ecological site description. Foliar cover is used to define plant community phases and states in the STM. Cover drives the transitions between communities and states because of the influence of shade and interception of rainfall.

Species composition by dry weight remains an important descriptor of the herbaceous community and of site productivity as a whole and includes both herbaceous and woody species. Calculating the similarity index requires data on species composition by dry weight.

Although there is considerable qualitative experience supporting the pathways and transitions within the state-and-transition model, no quantitative information exists that specifically identifies threshold parameters between Reference state and Disturbed state in this ecological site.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

The Reference State of the Loamy 15 to 19 inch ecological site consists of three dominant plant communities. Community 1.1 and 1.2 are dominated by a mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata spp. vasayana) overstory. Community 1.1 has a dominant understory of Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis) and the understory of community 1.2 is dominated by bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata). Community 1.1 is more predominant closer to the higher end of the effective precipitation range (15 to 19 inches) as Idaho fescue is better adapted to slightly wetter conditions (Zouhar, 2000). Community 1.3 occurs more often in valley or drainage bottoms where sandy loam soil textures are more prevalent. The community is comprised of a basin big sagebrush dominated overstory with a mixed perennial grass understory. The characteristics of the Loamy 15 to 19-inch ecological site allow for high productivity and diversity in the overstory and understory relative to other ecological sites within the Lost River Mountain LRU. Processes (natural and anthropogenic) that can result in state and community changes include frequent or severe fire occurrence, grazing that results in chronic defoliation, and land use changes (Davies et al., 2011).

Characteristics and indicators. The shift between communities at this ecological site is primarily driven by slight variations in local abiotic conditions. Shift in the understory composition from Idaho fescue to bluebunch wheatgrass is usually attributed to available moisture. Although Idaho fescue can be present closer to the 15-inch end of the effective precipitation range, bluebunch wheatgrass is better adapted to these conditions and tends to occupy a greater percentage of the canopy (Zouhar, 2000). Shift from an overstory canopy dominated by mountain big sagebrush to basin big sagebrush can be attributed to changes in soil texture and landform. Basin big sagebrush tends to dominate when soil texture conditions shift to sandy or silty loams and/or landforms that include floodplains, low stream terraces, and drainages (Tirmenstein, 1999).

Resilience management. This site has moderate to high resilience as a result of the cryic soil temperature regime and xeric soil moisture regime. Resistance and resilience of a specific site have been attributed to abiotic conditions favorable to plant growth and reproduction (Maestas et al. 2016). Soils that fall within the cryic (cold) temperature regime and xeric (wet) moisture regime tend to have higher diversity and production and are therefore more resilient, specifically in terms of resisting or recovering from invasion post-disturbance (Maestas et al., 2016). On the LRU scale, this site may also have increased resistance to post-disturbance invasion due to the biodiversity generally present at the site. Sites with high biodiversity have been shown to exhibit increased resistance and resilience as a result of the differential impact of disturbances such as insect, disease, and fire on the variety of species present (Oliver et al., 2015).

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata), shrub

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), grass

Community 1.1

Mountain Big Sagebrush and Idaho Fescue

Figure 10. Loamy reference site in the North end of the Lemhi range.

The mountain big sagebrush and Idaho fescue community is well adapted to the abiotic conditions found at this ecological site in the Lost River Mountain LRU. Both species thrive in loamy soil textures that lack carbonates, and high volumes of coarse fragments and occur on slopes less than 30 percent. Idaho fescue prefers slightly higher amounts of effective precipitation than the other grass species found at this ecological site. Understories dominated by this species become more predominant on the upper end of the 15 to 19-inch climatic subset (Zouhar, 2000). Of the big sagebrush sub-species, mountain big sagebrush has the greatest preference for sites with higher soil moisture availability. The species is commonly found on moderately deep to deep well-drained Mollisols, and at higher elevations than other big sagebrush species (Innes, 2017). In this community, mountain big sagebrush tends to exist as a monoculture in the overstory, however, other species of shrubs may be present at less than five percent canopy cover. Production in this community is high, ranging from 800 to 1,600 pounds per acre, with an average of just over 1,000 pounds per acre. Mountain big sagebrush foliar cover averages 24 percent, while Idaho fescue averages 22 percent. Species of lupine (Lupinus sp.) and sulfur flower buckwheat (Eriogonum umbellatum) each average six percent canopy cover respectively.

Resilience management. With mountain big sagebrush being the primary overstory species, this community in the reference state exhibits low to moderate resilience. Mountain big sagebrush is drought intolerant. Sagebrush foliage is highly flammable and because they are among the most productive of sagebrush species, fuel loading and continuity are higher (Innes, 2017). This increases susceptibility to severe wildfire events at more frequent intervals which can slow recovery. Fires in mountain big sagebrush communities tend to be stand replacing and under poor post-disturbance conditions, recovery to pre-fire levels can exceed 75 years. When Idaho fescue is the dominant understory, fire return intervals can be as frequent as 10 to 15 years. Although Idaho fescue fares better than mountain big sagebrush during fire events, mortality averages between 20 and 50 percent and can exceed 75 percent after severe events (Zouhar, 2000). Severe or frequent fire events prompt a shift into the Disturbed State. The effective precipitation received at this site (15 to 19-inch) adds resilience. Available moisture has shown to be a key component of successful post-disturbance recovery (Chamber et al., 2014).

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

sulphur-flower buckwheat (Eriogonum umbellatum), other herbaceous

-

lupine (Lupinus), other herbaceous

Figure 11. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 375 | 500 | 750 |

| Shrub/Vine | 350 | 400 | 600 |

| Forb | 75 | 125 | 225 |

| Total | 800 | 1025 | 1575 |

Table 8. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 24-40% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 15-25% |

| Forb foliar cover | 8-22% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 55-90% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-10% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-2% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 2-8% |

Table 9. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1-3% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 3-7% |

| Forb basal cover | 1-2% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 2-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-4% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 50-85% |

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). ID0705, ARTRV–PSSPS-FEID. State 1.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 35 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.2

Mountain Big Sagebrush and Bluebunch Wheatgrass.

The mountain big sagebrush and bluebunch wheatgrass community is most prevalent on the lower end of the 15 to 19-inch climatic subset of the Loamy ecological site. Bluebunch wheatgrass is able to thrive under a broad range of moisture conditions and is one of the most drought-resistant native bunchgrasses (Zlatnik, 1999). These adaptations often allow bluebunch wheatgrass to become the dominant understory at the drier sites in the 15 to 19-inch climatic subset. Although both Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass populations can be present in this community, canopy cover and percentage of total production will be higher for bluebunch wheatgrass. Mountain big sagebrush remains the dominant overstory species. Other shrub species that may be present at a limited canopy cover include mountain snowberry (Symphoricarpos oreophilus), yellow rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus), and spineless horsebrush (Tetradymia canescens). Production in this community is high, ranging from 800 to 1,600 pounds per acre, with an average of 1,100 pounds per acre. Mountain big sagebrush foliar cover averages 28 percent. Bluebunch wheatgrass averages 23 percent. Idaho fescue is sub-dominant in the understory averaging 15 percent canopy cover. Species of lupine (Lupinus sp.) and phlox (Phlox sp.) each average three percent canopy cover.

Resilience management. With mountain big sagebrush being the primary overstory species, this community exhibits low to moderate resilience. Of all the big sagebrush sub-species, mountain big sagebrush is the least drought tolerant. Sagebrush foliage is highly flammable and because they are among the most productive of sagebrush species, fuel loading and continuity are higher (Innes, 2017), increasing susceptibility to severe wildfire events at more frequent intervals which can slow recovery. Fires in mountain big sagebrush stands tend to be stand replacing and under poor conditions, recovery to pre-fire levels can exceed 75 years (Innes, 2017). Bluebunch wheatgrass has a higher survival rate because growth points are protected. Fire return intervals are generally less than 30 years depending on overstory and related vegetation. Recovery of bluebunch wheatgrass from fire is rapid, returning to pre-disturbance populations in less than five years (Zlatnik, 1999). Although bluebunch wheatgrass populations may survive severe fire events, if the mountain big sagebrush overstory is removed, this can prompt a shift into the Disturbed State. The volume of effective precipitation received at this site (15 to 19-inch) adds resilience. Available moisture has shown to be a key component of successful post-disturbance recovery (Chamber et al., 2014).

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), grass

-

lupine (Lupinus), other herbaceous

-

phlox (Phlox), other herbaceous

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 10. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 425 | 500 | 575 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 400 | 475 | 525 |

| Forb | 100 | 175 | 225 |

| Total | 925 | 1150 | 1325 |

Table 11. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 18-33% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 14-36% |

| Forb foliar cover | 7-13% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 15-35% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-10% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 1-9% |

Table 12. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1-3% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 3-6% |

| Forb basal cover | 0-2% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 4-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-4% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 60-80% |

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). ID0705, ARTRV–PSSPS-FEID. State 1.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 35 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.3

Basin Big Sagebrush/Mixed Perennial Grass

The basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata spp. tridentata) mixed perennial grass community occurs within the Loamy 15 to 19 Inch Precipitation Zone ecological site under specific localized landform and soil conditions. Basin big sagebrush establishes well in deep, sandy loam soils that exist within valley and drainage bottoms, in or near floodplains, and portions of stream terraces of the Loamy ecological site. The species does well at the drier end of the 15 to 19-inch effective precipitation range, able to take advantage of deep moisture accumulations in the soil (Tirmenstein, 1999). Canopy cover shifts to mountain big sagebrush as distance increases from these respective landforms and conditions. The understory is a mix of perennial grass species, bluebunch wheatgrass being the most predominant. Forb composition and canopy cover are similar to the other two communities in this state. Production values in this community range from 700 to 1,100 pounds per acre, averaging 850 pounds per acre. The species that contribute the most to overall production values include basin big sagebrush, bluebunch wheatgrass, and mountain big sagebrush.

Resilience management. The basin big sagebrush/mixed perennial grass community is impacted by three primary disturbance regimes; severe or frequent fire, grazing that results in chronic defoliation, and periodic drought that stresses vegetation and can result in mortality. The community has low to moderate resilience to fire, and moderate resilience to grazing and drought. Under most circumstances, basin big sagebrush mortality is very high following a fire disturbance event and fire return intervals range between 15 and 70 years. However, basin big sagebrush produces a high volume of seeds annually with high germination rates. If a nearby population exists post-disturbance, recovery time can be greatly reduced (Tirmenstein, 1999). Bluebunch wheatgrass has a high survival rate because its growth points are protected. Fire return intervals are generally less than 30 years depending on overstory and related vegetation. Recovery of bluebunch wheatgrass from fire is rapid, returning to pre-disturbance populations in less than five years (Zlatnik, 1999). Although bluebunch populations may survive severe fire events, if the mountain big sagebrush overstory is removed, this can prompt a shift into the Disturbed State. Moderate, long-term grazing has shown to have a minor impact overall on basin big sagebrush overstory; however, understory grasses such as bluebunch wheatgrass can become more vulnerable to other disturbances as a result (Davies et al., 1998). Basin big sagebrush is able to take advantage of deep available soil moisture and bluebunch wheatgrass is well adapted to low and variable annual precipitation. This allows both species to function relatively well under drought conditions (Tirmenstein, 1999 & Zlatnik, 1999).

Dominant plant species

-

basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata), shrub

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), grass

-

thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolatus), grass

-

Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), grass

-

phlox (Phlox), other herbaceous

Figure 15. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 13. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 350 | 400 | 500 |

| Shrub/Vine | 300 | 375 | 475 |

| Forb | 50 | 75 | 125 |

| Total | 700 | 850 | 1100 |

Table 14. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 20-48% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 20-40% |

| Forb foliar cover | 3-15% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-3% |

| Litter | 35-65% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 3-12% |

Table 15. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1-3% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 2-5% |

| Forb basal cover | 1-3% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 60-80% |

Figure 16. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). ID0906, ARTRT/PSSP6.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway P1-2

Community 1.1 to 1.2

The transition from Community 1.1 to Community 1.2 is primarily driven by localized effective precipitation. Bluebunch wheatgrass is able to outcompete Idaho fescue at the lower end of the 15 to 19-inch effective precipitation range, allowing it to become the dominant understory species. When conditions are slightly wetter, Idaho fescue establishes well and can dominate the understory composition. Mountain big sagebrush functions well in both communities as the dominant overstory species.

Context dependence. The abiotic conditions that result in community transitions from Community 1.1 to 1.2 are site-specific and not directly influenced by anthropogenic or biotic interactions.

Pathway P1-P3

Community 1.1 to 1.3

The transition from community 1.1 to 1.3 is a result of localized abiotic conditions surrounding landform and soil properties. The overstory composition dominated by Basin big sagebrush in community 1.3 indicates that soils have transitioned to sandy and silty loams. Basin big sagebrush prefers deep, sandier soils across the 15 to 19-inch precipitation range and because of these preferences, these communities often occur along drainages, valley bottoms, and floodplain steps. The understory in this community can be dominated by either bluebunch wheatgrass or Idaho fescue, but tends to be more diverse in grasses than in Community 1.1.

Context dependence. The abiotic conditions that result in transitions from Community 1.1 to 1.3 are site specific and not directly influenced by anthropogenic or biotic interactions.

State 2

Disturbed

Figure 17. Grazed site with a mixed overstory of threetip sagebrush, basin big sagebrush, and rabbitbrush.

The Disturbed state is a result of both natural and anthropogenic disturbance events that result in widespread sagebrush mortality at a given site. The primary natural disturbance resulting in sagebrush mortality at this ecological site is severe or frequent wildfire; however, intense freeze events and insect and disease can also occur. Both mountain big sagebrush and basin big sagebrush are particularly susceptible to stand-replacing fires and often experiences complete canopy loss during moderate and severe wildfire events (Innes, 2017 & Tirmenstein, 1999). Because this LRU exists primarily on publicly managed lands (US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and State), widespread anthropogenic disturbance events are infrequent. Examples of anthropogenic disturbance events include brush management through sagebrush mowing or removal treatments, chemical treatments, or improper grazing techniques that result in high-intensity hoof disturbance or chronic defoliation. A combination of natural and anthropogenic disturbance is possible and can result in increased severity of disturbance, decreased resilience, and greater difficulty returning to the Reference State. For example, intense grazing that results in significant defoliation post-fire disturbance can increase bare ground cover, increase erosion potential, and slow the reestablishment of native grass species that preclude the return of overstory sagebrush canopy (Zlatnik, 1999).

Characteristics and indicators. The primary indicator of the Disturbed State is a near-complete loss of overstory sagebrush species, often replaced by shrub species that are able to take advantage of the local disturbance regime. Common replacement species include Artemisia tripartita (threetip sagebrush) and Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus (yellow rabbitbrush). A shift towards an increase in native and disturbance-tolerant grasses and forbs is likely with the removal of resource competition associated with the sagebrush overstory presence. Severe disturbance events also increase the opportunity for invasion of annual grasses and weeds such as cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and thistle species. The canopy cover percentage of these species is usually dependent on the distance of a seed source post-disturbance, but mostly stays under five percent (Zlatnik, 1999).

Resilience management. Resilience in this state is moderate. Many of the post-disturbance grasses and shrubs that are common in this state establish quickly and reach a representative canopy within 10 years post-disturbance. Grasses and shrubs continue to increase until the overstory canopy of sagebrush begins to return. However, local resilience in this state is highly dependent on current soil moisture availability, seed sources, timing and severity of the disturbance. In the instance of fire disturbance, bluebunch wheatgrass mortality can be significantly lower if the fire occurs in the spring as opposed to fall. Recovery can be impacted by the quantity of immediate post-fire precipitation (Zlatnik, 1999). More severe disturbances increase possibility of post-disturbance invasion. The greater the establishment of invasives, the lower the site resilience becomes.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), grass

-

phlox (Phlox), other herbaceous

-

Indian paintbrush (Castilleja), other herbaceous

Community 2.1

Bunchgrass and Yellow Rabbitbrush

The bunchgrass and yellow rabbitbrush community is driven by the disturbance related removal of the primary overstory of sagebrush species. Both natural and anthropogenic disturbances that result in near complete removal of the sagebrush overstory create opportunities for increased establishment of both native and non-native grasses and forbs, as well as disturbance tolerant shrubs. In this community, the primary sagebrush removing disturbance at this ecological site is severe or frequent fire. The frequency and severity of these fire disturbances are highly influenced by the overstory composition of the specific site in the reference state prior to disturbance. The composition and extent of the sagebrush species in the overstory impacts that respective fire regime. Communities in the Reference State with either a basin or mountain big sagebrush overstory are highly susceptible to stand-replacing fire events with fire return intervals ranging from five to 70 years (Innes, 2017 & Termenstein, 1999). This increases the likelihood of transition from the Reference State to the Disturbed State (community 2.1) following fire disturbances.

Resilience management. This plant community is moderately resilient because the grasses and forbs that dominate the composition are resistant to a variety of disturbances and able to re-establish quickly in the event of more severe disturbances. Both bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegenaria spicata) and Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda) are rarely harmed by fire events except for in the most severe instances. Both plants are able to reduce the amount of heat transfer to the root systems, allowing successful regrowth (Zlatnik, 1999 & Howard, 1997). Studies show that in the absence of grazing, bluebunch wheatgrass-dominated systems are able to return to pre-fire production levels eight years post-disturbance (Zlatnick, 1999). Sandberg bluegrass has been shown to fully re-establish post-plowing events in as little as 7 years (Howard, 1997). Idaho fescue (Festuca Idahoensis) is less resilient to both fires and grazing. Idaho fescue can often survive low severity fires, however, moderate to severe fires are more destructive, resulting in a 30-year return to pre-disturbance canopy cover (Zouhar, 2000). Both yellow rabbitbrush and rubber rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosa) are often the first shrub species to re-establish on this ecological site following a disturbance and can increase in relation to the severity or frequency of the disturbance. Although yellow rabbitbrush can exist in relatively small numbers within the Reference State, it becomes the dominant shrub species in highly disturbed systems (Terminstein, 1999).

Dominant plant species

-

yellow rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus), shrub

-

bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), grass

-

Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), grass

-

phlox (Phlox), other herbaceous

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), other herbaceous

Figure 18. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 16. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 450 | 740 | 900 |

| Shrub/Vine | 0 | 85 | 200 |

| Forb | 15 | 50 | 100 |

| Total | 465 | 875 | 1200 |

Table 17. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0-8% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 15-40% |

| Forb foliar cover | 3-9% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-2% |

| Litter | 5-40% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 18. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0-2% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 2-6% |

| Forb basal cover | 0-2% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-25% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 45-85% |

Figure 19. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). ID1205, FEID-PSSPS. State 1.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 25 | 30 | 25 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Community 2.2

Threetip Sagebrush and Mixed Perennial Grass

Figure 20. Heavily grazed site on the Southern end of the Lost River Range

The threetip sagebrush and mixed perennial grass Community is a disturbance impacted community driven by moderate to high grazing pressure that results in chronic defoliation and/or hoof related disturbances. This community is marked by at least a five percent canopy cover of threetip sagebrush which is disturbance tolerant, though may not be the dominant canopy cover. Basin big and mountain big sagebrush may also be present in the canopy at varying densities. The understory is a mix of perennial grasses dominated by Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda) and bluebunch wheatgrass. The canopy cover of these species can vary based on grazing pressure impacts (timing, frequency, intensity, duration). Forb cover is usually less dense and less diverse than the Reference State. Invasive species such as cheatgrass (Bromus techtorum) and non-native thistle can also be present at canopy covers of less than five percent. Overall production for this community is lower than all communities in the Reference State, primarily due to the loss of dominance by either bluebunch wheatgrass or Idaho fescue, both of which contribute significantly to overall production in the Reference State. Production values range from 400 to 900 pounds per acre, averaging 650 pounds per acre.

Resilience management. This community has low to moderate resilience. As grazing pressure increases, the the composition of the understory changes. Herbivory and hoof-related disturbance open opportunities for the immigration of invasive species, some of which can significantly alter ecosystem dynamics. Certain studies have shown that although the composition and density of plant species may remain intact over long periods under moderate grazing pressure, the community becomes more susceptible to impacts of other disturbance regimes such as wildfire (Davies et al. 2018).

Dominant plant species

-

basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata), shrub

-

threetip sagebrush (Artemisia tripartita), shrub

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), grass

-

thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus), grass

-

bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), grass

-

arrowleaf balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata), other herbaceous

-

tapertip hawksbeard (Crepis acuminata), other herbaceous

Figure 21. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 19. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 175 | 300 | 400 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 175 | 250 | 350 |

| Forb | 50 | 100 | 150 |

| Total | 400 | 650 | 900 |

Table 20. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 23-50% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 25-50% |

| Forb foliar cover | 3-12% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-3% |

| Litter | 55-80% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 5-25% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 2-11% |

Table 21. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 2-5% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 3-6% |

| Forb basal cover | 0-2% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 5-25% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-3% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 40-70% |

Figure 22. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). ID0906, ARTRT/PSSP6.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway P1-2

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Community 2.1 is driven by wildfire disturbance, whereas community 2.2 is driven by grazing pressure that results in chronic defoliation. The dynamics of the transition from Community 2.1 to 2.2 would greatly depend on the stage of fire recovery following the disturbance event. If the sagebrush or shrub overstory has not recovered and heavy grazing is introduced, community 2.2 will present (and be maintained) with little shrub overstory canopy cover. If the shrub overstory has recovered, the impact will primarily be on the understory grass species.

Context dependence. The outcome of a shift from Community 2.1 to 2.2 is heavily dependent on grazing variables including timing, duration, frequency, intensity, and what period of recovery the initial community was in.

Pathway P2-1

Community 2.2 to 2.1

The transition from Community 2.2 to 2.1 is a result of severe or frequent wildfire disturbance event. When a moderate to severe wildfire occurs, overstory sagebrush canopy is removed and canopy cover and composition of the grass and forb understory can be greatly altered. Recovery timeframes can vary based on initial plant composition, distance from seed source, post-disturbance weather patterns, grazing strategies, and the addition of any post-disturbance seeding or planting efforts.

Context dependence. Moderate grazing regimes that result in chronic defoliation over extended periods of time can alter ecological dynamics and change the fire ecology of an ecological site. Increases in the abundance of fire prone invasive species such as cheatgrass (Bromus techtorum) and changes in grass structure can shorten fire return intervals and result in more severe disturbances (Davies et al., 2018). Fire disturbance events must be severe enough to remove the majority of the overstory canopy for the transition to occur.

Transition T1-2

State 1 to 2

Transition from the Reference to the Disturbed State is a mechanism of moderate to severe disturbance, both natural and anthropogenic. The most likely disturbance to cause this transition is wildfire. Other disturbances include but are not limited to freeze kill events, insect and disease, overgrazing, and mechanical brush removal.

Constraints to recovery. The primary constraint to recovery is the distance to a seed source and time. When the disturbance is severe and the extent is great, seed source populations for sagebrush species may be removed from the vicinity. In this case, immigration and re-establishment of overstory sagebrush species can be slow. Re-establishment to pre-disturbance canopy cover and extent of mountain big sagebrush cover generally exceeds 25 years even in ideal conditions (Innes, 2017). This time period can be greatly reduced through seeding and planting interventions.

Context dependence. The primary factors driving the likelihood of restoration success are post-disturbance weather patterns and the distance from viable seed sources. Disturbances that cover a larger extent increase distance to seed sources. Prolonged periods of drought can slow restoration processes. Alternately, average to above-average precipitation post-disturbance can greatly increase speed and success in the re-establishment of sagebrush species (Robin, 2017; Steinberg, 2002; and Fryer, 2009).

Restoration pathway R2-1

State 2 to 1

The most important mechanism driving restoration from the disturbed state to the reference is time without sagebrush removing disturbance. Distance from overstory species (sagebrush) seed source can also impact the speed of restoration. Seeding or planting of desired overstory species found in the Reference state can speed restoration efforts.

Context dependence. Restoration is highly dependent on time without disturbance. New sagebrush seedlings are moderately sensitive to disturbances such as flood, freeze, and insect and disease. They are highly sensitive to herbivory and even low-severity fire events (Fryer, 2009 & Steinberg 2002). Seeding and planting of desired species can speed up the restoration process, however; regeneration success with or without planting is highly dependent on localized weather patterns during the restoration period. Periods of drought will slow the process significantly, whereas periods of above-normal precipitation aid in sagebrush regeneration and establishment (Innes, 2017; Steinberg 2002 & Fryer, 2009).

Additional community tables

Table 22. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | 300–550 | |||||

| mountain big sagebrush | ARTRV | Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana | 280–350 | 10–38 | ||

| antelope bitterbrush | PUTR2 | Purshia tridentata | 0–50 | 0–5 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 0–48 | 0–3 | ||

| mountain snowberry | SYOR2 | Symphoricarpos oreophilus | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 0–10 | 0–2 | ||

| rubber rabbitbrush | ERNA10 | Ericameria nauseosa | 0–10 | 0–2 | ||

| rose | ROSA5 | Rosa | 0–10 | 0–2 | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | 350–650 | |||||

| Idaho fescue | FEID | Festuca idahoensis | 250–350 | 10–47 | ||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 0–150 | 0–15 | ||

| Ross' sedge | CARO5 | Carex rossii | 0–80 | 0–3 | ||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 0–80 | 1–3 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–70 | 0–4 | ||

| bluegrass | POA | Poa | 0–64 | 0–4 | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–50 | 2 | ||

| basin wildrye | LECI4 | Leymus cinereus | 0–30 | 1 | ||

| needlegrass | ACHNA | Achnatherum | 0–15 | 0–1 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | 50–200 | |||||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 10–175 | 1–8 | ||

| sulphur-flower buckwheat | ERUM | Eriogonum umbellatum | 5–50 | 1–10 | ||

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | 5–50 | 1–3 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–50 | 0–2 | ||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 0–24 | 0–1 | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | 0–20 | 0–1 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–10 | 0–1 | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 0–10 | 0–1 | ||

| beardtongue | PENST | Penstemon | 0–10 | 0 | ||

| hawksbeard | CREPI | Crepis | 0–8 | 0–1 | ||

| cushion buckwheat | EROV | Eriogonum ovalifolium | 0–8 | 0–1 | ||

| ballhead sandwort | ARCO5 | Arenaria congesta | 0 | 0 | ||

| ragwort | SENEC | Senecio | 0 | 0 | ||

Table 23. Community 1.2 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | 400–600 | |||||

| mountain big sagebrush | ARTRV | Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana | 300–540 | 15–25 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 24–150 | 1–8 | ||

| mountain snowberry | SYOR2 | Symphoricarpos oreophilus | 0–24 | 0–3 | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 0–24 | 0–1 | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | 250–650 | |||||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 100–360 | 10–15 | ||

| muttongrass | POFE | Poa fendleriana | 0–150 | 0–15 | ||

| Idaho fescue | FEID | Festuca idahoensis | 25–150 | 2–7 | ||

| bluegrass | POA | Poa | 60–150 | 2–5 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 15–83 | 1–3 | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–60 | 0–5 | ||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 0–12 | 0–1 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | 100–250 | |||||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 12–150 | 1–5 | ||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 10–150 | 1–4 | ||

| western stoneseed | LIRU4 | Lithospermum ruderale | 0–48 | 0–2 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–40 | 0–5 | ||

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | 0–20 | 0–1 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–12 | 0–2 | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | 0–12 | 0–1 | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 0–12 | 0–1 | ||

| aster | ASTER | Aster | 0–12 | 0–1 | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | 0–12 | 0–1 | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 0–10 | 0–2 | ||

| bushy bird's beak | CORA5 | Cordylanthus ramosus | 0–10 | 0–1 | ||

| beardtongue | PENST | Penstemon | 0–10 | 0–1 | ||

Table 24. Community 1.3 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | 300–475 | |||||

| basin big sagebrush | ARTRT | Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata | 100–200 | 15–36 | ||

| mountain big sagebrush | ARTRV | Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana | 50–175 | 5–20 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 10–100 | 1–5 | ||

| rubber rabbitbrush | ERNA10 | Ericameria nauseosa | 0–40 | 0–3 | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | 350–500 | |||||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 75–175 | 8–15 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 25–100 | 3–15 | ||

| Columbia needlegrass | ACNE9 | Achnatherum nelsonii | 0–100 | 0–5 | ||

| thickspike wheatgrass | ELLA3 | Elymus lanceolatus | 5–50 | 1–5 | ||

| cheatgrass | BRTE | Bromus tectorum | 0–30 | 0–3 | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–30 | 0–3 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | 50–125 | |||||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 5–25 | 1–5 | ||

| clover | TRIFO | Trifolium | 0–25 | 0–3 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–15 | 0–3 | ||

| maiden blue eyed Mary | COPA3 | Collinsia parviflora | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| pepperweed | LEPID | Lepidium | 0–10 | 0–2 | ||

| sego lily | CANU3 | Calochortus nuttallii | 0–5 | 0–2 | ||

| alumroot | HEUCH | Heuchera | 0–5 | 0–2 | ||

Table 25. Community 2.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | 0–250 | |||||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 10–150 | 1–8 | ||

| mountain big sagebrush | ARTRV | Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana | 0–100 | 0–5 | ||

| basin big sagebrush | ARTRT | Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata | 0–100 | 0–5 | ||

| rubber rabbitbrush | ERNA10 | Ericameria nauseosa | 0–50 | 0–3 | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | 450–900 | |||||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 300–650 | 8–30 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–175 | 0–5 | ||

| Idaho fescue | FEID | Festuca idahoensis | 0–150 | 0–3 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | 15–100 | |||||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 0–25 | 0–4 | ||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 0–25 | 0–4 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–20 | 0–2 | ||

Table 26. Community 2.2 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | 175–400 | |||||

| basin big sagebrush | ARTRT | Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata | 100–250 | 12–30 | ||

| threetip sagebrush | ARTR4 | Artemisia tripartita | 25–125 | 5–15 | ||

| mountain big sagebrush | ARTRV | Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana | 25–125 | 5–15 | ||

| rubber rabbitbrush | ERNA10 | Ericameria nauseosa | 10–75 | 1–8 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 5–50 | 1–8 | ||

| mountain snowberry | SYOR2 | Symphoricarpos oreophilus | 0–50 | 0–3 | ||

| slender buckwheat | ERMI4 | Eriogonum microthecum | 0–25 | 0–3 | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | 175–350 | |||||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 10–150 | 5–25 | ||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 15–150 | 3–15 | ||

| bluegrass | POA | Poa | 0–100 | 0–15 | ||

| thickspike wheatgrass | ELLAL | Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus | 0–100 | 0–12 | ||

| Columbia needlegrass | ACNE9 | Achnatherum nelsonii | 0–75 | 0–8 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | 50–150 | |||||

| arrowleaf balsamroot | BASA3 | Balsamorhiza sagittata | 0–60 | 0–4 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–60 | 0–3 | ||

| tufted fleabane | ERCA2 | Erigeron caespitosus | 0–50 | 0–3 | ||

| longleaf phlox | PHLO2 | Phlox longifolia | 0–50 | 0–3 | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Listed below are production ranges for each community in the Loamy 15 - 19 Inch Precipitation Zone ecological site. These values can be used to estimate stocking rates, however, community composition as listed in this ecological site description may not entirely match the current composition at a given site. Field visits to document actual plant composition and production should be conducted to calculate actual stocking rates at a given location.

Communities and Production Ranges (in pounds per acre):

In the Reference state, the production for each community is as follows: Community 1.1 ranges from 800 to 1,600, averaging 1,000; Community 1.2 ranges from 800 to 1,600, averaging 1,100; Community 1.3 ranges from 700 to 1,100, averaging 850. In the Disturbed state, Community 2.1 ranges from 465 to 1,175, averaging 840 and Community 2.2 ranges from 400 to 900, averaging 650.

Wildlife Interpretations:

Sagebrush steppe ecosystems in the Western United States cover nearly 165 million acres and provide vital habitat for over 170 different species of birds and mammals (NWF, 2022).

The sagebrush grasslands in the Lost River Mountain LRU provide critical winter range for mule deer, elk, pronghorn and moose. The LRU also encompasses critical habitat for greater sage grouse populations in the Lemhi, Lost River, and White Knob Mountain mountain ranges. Sage grouse priority planning areas have been identified by the Challis Sage Grouse Local Working group in Grouse and Morse Creek, the Upper Pahsimeroi north of Sawmill Canyon, Mackay Bar, and Barton Flats (CSLWG, 2007). According to Idaho Fish and Game Management spatial layers developed in conjunction with the Bureau of Land Management, US Forest Service, and US Fish and Wildlife Service, greater sage grouse general habitat exists on the northern end of the White Knob Mountain range, northern end of the Pahsimeroi Mountain range, and portions of the eastern side of the Lemhi and White Knob Mountain ranges. More importantly to the species, significant areas designated important and priority habitat have been identified across the entirety of the White Knob, Lost River, and Lemhi mountain ranges.

The following are dominant plant species within this ecological site and their associated value to wildlife present in the LRU:

Mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana) - Communities 1.1/1.2:

Mountain big sagebrush is considered to be highly palatable by most wildlife browsers (Rosenstrater, 2005). Sage grouse, ungulates, and rodents browse mountain big sagebrush primarily during the winter when it becomes one of the more palatable available forages. However, seasonal snow levels can exclude many browsing species. Several studies have shown that Mountain big sagebrush is preferred forage by elk, mule deer, and sage grouse when compared to the other big sagebrush species (Innes, 2017). Sage grouse are considered obligate species of mountain big sagebrush and other big sagebrush varieties. These species are generally preferred over the low sagebrush species; Artemisia nova and Artemisia arbuscula (Dalke et al., 1963).

Basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata spp. tridentata) - Communities 1.3/2.2:

Basin big sagebrush is a forage species for sage grouse, mule deer, pronghorn, and elk, though it is considered the least desirable of the big sagebrush species. It is more highly utilized during severe winters when other species are not available. Pygmy rabbits feed on basin big sagebrush extensively, though will also consume other big sagebrush species (Tirmenstein, 1999).

Threetip sagebrush (Artemisia tripartita) - Community 2.1:

Three tip sagebrush is not a preferred browse species for most wild ungulates. It can be used to a minor extent by mule deer in both the winter and summer and as emergency forage for other large ungulates (Tirmenstein, 1999.)

Antelope bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata) - Community 1.1/1.2:

Antelope bitterbrush is a very important browse species for pronghorn, mule deer, elk, bighorn sheep and moose. This is especially true towards the end of the summer season when the forage becomes more valuable. Mule deer diets in September can be comprised of up to 91 percent antelope bitterbrush when available. The species becomes a critical food source for many wild ungulates during the winter season (Zlatnik, 1999). Antelope bitterbrush is also important to many insect species including pogonomyrmex ants which utilize the seed for food and tent caterpillars which utilize the canopy (Furniss, 1983).

Mountain snowberry (Symphoricarpos oreophilus) - Community 1.1/1.2/2.2:

Mountain snowberry can be a valuable early-season forage for wild ungulates as it is one of the first palatable species to leaf out in the spring. In high elevation summer ranges it is an important forage species for deer and elk. The fruits are utilized by a few upland birds such as grouse, pheasants, and magpies (Aleksoff, 1999).

Bluebunch wheatgrass (Psuedoeogenaria spicata) - All states/communities:

Bluebunch wheatgrass is considered one of the most important forage species on Western rangelands for both livestock and wildlife (Sours, 1983). In Idaho, utilization of bluebunch wheatgrass by elk was medium-high, medium for mule deer, high for bighorn sheep, and low for pronghorn (Zlatnik, 1999).

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis) - Possible in all states/communities

When available, Idaho fescue can be a dominant component to many wild ungulate diets, including pronghorn, deer, elk, and bighorn sheep. In some instances depending on other available forage, the species can be considered as valuable but not preferred forage for ungulates. The species is a valuable component to the diet of the Northern pocket gopher and grizzly bear when it is found within their range.

Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda) - Possible in all states/communities

Sandberg bluegrass is one of the earliest grasses to green up during the spring and become available forage for wildlife; however becomes less utilized during the later summer months. The degree of use for elk and pronghorn is good to poor, and good to fair for mule deer, small mammals, small nongame birds, and upland game birds. Usage is fair to poor by waterfowl (Howard, 1997).

Hydrological functions

Water in the form of annual precipitation is the primary limiting factor of total plant production on this ecological site. Soils associated with this ecological site are primarily associated with hydrologic group B. Runoff potential ranges from moderate to rapid and soil permeability is slow to moderate. Water transmission through the soil is unimpeded.

Higher infiltration rates and lower runoff rates tend to coincide with ground cover percentage. Reduced infiltration and increased runoff have the greatest potential when ground cover is less than 50 percent.

Recreational uses

This ecological site provides hunting opportunities for upland game birds and large game animals including pronghorn, mule deer, elk, and moose. Many trails and campsites exist within the LRU and are maintained by public land management agencies.

The diverse plants that exist in this LRU and on this ecological site have an aesthetic value that appeals to recreationists.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Data collection intensity and site ID's are provided for each community phase identified within each state used to develop this ecological site description. Tier III data sets include five rangeland inventory protocols: Line point intercept, canopy/basal gap, production, continuous line intercept for overstory canopy, and soil stability. Tier II datasets include line point intercept and at least one other survey. Tier I datasets include an ocular macroplot survey that involved a site plant census, canopy cover estimates, production by species estimates, and total site production estimates.

(Order = Site ID, state/community phase, location, and survey intensity)

NASIS ID State/Comm Location Intensity

2019ID7032038 1.1 White Knob Mtns Low

2021ID7200013 1.1 Lemhi Range High

2021ID7200097 1.1 Lemhi Range High

2020ID7032178 1.1 Lost River Mtns low

2020ID7033128 1.1 Lost River Range High

2019ID7031078 1.1 White Knob Mtns Low

2019ID7032041 1.2 White Knob Mtns Low

2019ID7031079 1.2 White Knob Mtns Low

2019ID7032063 1.2 White Knob Mtns High

2019ID7033055 1.2 White Knob Mtns Low

2020ID7031159 1.2 Lost River Mtns Low

2020ID7031124 1.3 Lost River Mtns High

2020ID7033109 2.2 Lost River Mtns High

Other references

Aleksoff, Keith C. 1999. Symphoricarpos oreophilus. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Bestelmeyer, B., J.R. Brown, K.M. Havstad, B. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J.E. Herrick. 2003. Development and Use of State and Transition Models for Rangelands. Jornal of Range Management 56:114–126.

Bestelmeyer, B. and J.R. Brown. 2005. State-and-Transition Models 101: a Fresh Look at Vegetation Change.

Bestelmeyer, B., J.R. Brown, J.E. Herrick, D.A. Trujillo, and K.M. Havstad. 2004. Land Management in the American Southwest: a state-and-transition approach to ecosystem complexity. Environmental Management 34:38–51.

Bestelmeyer, B.T., K. Moseley, P.L. Shaver, H. Sanchez, D.D. Briske, and M.E. Fernandez-Gimenez. 2010. Practical guidance for developing state-and-transition models. Rangelands 32:23–30.

Blaisdell, James P.; Murray, Robert B.; McArthur, E. Durant. 1982. Managing Intermountain rangelands--sagebrush-grass ranges. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-134. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 41 p.

Chambers, J.C., J.L. Beck, T.J. Christiansen, K.J. Clause, J.B. Dinkins, K.E. Doherty, K.A. Griffin, D.W. Havlina, K.F. Henke, L.L. Kurth, J.D. Maestas, M. Manning, K.E. Mayer, B.A. Mealor, C. McCarthy, M.A. Perea, and D.A. Pyke. 2016. Using resilience and resistance concepts to manage threats to sagebrush ecosystems, Gunnison sage-grouse, and Greater sage-grouse in their eastern range: A strategic multi-scale approach.. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-356.. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO. 1–143.

Challis Sage-grouse Local Working Group (CSLWG). 2007. Challis Sage-grouse Conservation Plan.

Chambers, J.C., D.A. Pyke, J.D. Maestas, M. Pellant, C.S. Boyd, S.B. Campbell, S. Esipinosa, D.W. Havlina, K.E. Mayer, and A. Wuenschel. 2014. Using resistance and resilience concepts to reduce impacts of invasive annual grasses and altered fire regimes on the sagebrush ecosystem and greater sage-grouse: A strategic multi-scale approach.. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-326.. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station., Fort Collins, CO. 73.

Clary, Warren P.; Beale, Donald M. 1983. Pronghorn reactions to winter sheep grazing, plant communities, and topography in the Great Basin. Journal of Range Management. 36(6): 749-752.

Dalke, Paul D.; Pyrah, Duane B.; Stanton, Don C.; Crawford, John E.; Schlatterer, Edward F. 1963. Ecology, productivity, and management of sage grouse in Idaho. Journal of Wildlife Management. 27(4): 810-841.

Daubenmire, R. F. (1940). Plant Succession Due to Overgrazing in the Agropyron Bunchgrass Prairie of Southeastern Washington. Ecology, 21(1), 55–64.

Davies, K. Boyd, C. Bates, J. Eighty Years of Grazing by Cattle Modifies Sagebrush and Bunchgrass Structure. 2018. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 71(3):27

Fryer, Janet L. 2009. Artemisia nova. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/artnov/all.html

Forest Service Remote Automoted Weather Station (Bonanza & Copper Basin). Retrieved from: Western Regional Climate Center. October, 2022. https://wrcc.dri.edu/

Francis, John K. ed. 2004. Wildland shrubs of the United States and its Territories: thamnic descriptions: volume 1. Gen. Tech. Rep. IITF-GTR-26. San Juan, PR: USDA, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, and Fort Collins, CO: USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 830 p.

Fryer, Janet L. 1997. Amelanchier alnifolia. In: Fire Effects

Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Furniss, Malcolm M. 1983. Entomology of antelope bitterbrush. In: Tiedemann, Arthur R.; Johnson, Kendall L., compilers. Proceedings--research and management of bitterbrush and cliffrose in western North America; 1982 April 13-15; Salt Lake City, UT. General Technical Report INT-152. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 164-172.

Howard, Janet L. 1997. Poa secunda. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/graminoid/poasec/all.html

Innes, Robin J. 2017. Artemisia tridentata subsp. vaseyana, mountain big sagebrush. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/arttriv/all.html

Johnson, Kathleen A. 2000. Prunus virginiana. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Kindschy, Robert R.; Sundstrom, Charles; Yoakum, James D. 1982. Wildlife habitats in managed rangelands--the Great Basin of southeastern Oregon: pronghorns. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-145. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 18 p.

Kirk W. Davies, Jon D. Bates, Rory O'Connor. 2021. Long-term evaluation of restoring understories in Wyoming big sagebrush communities with mowing and seeding native bunchgrasses. Rangeland Ecology & Management, Volume 75, Pages 81-90.

Knick, S.T.; Holmes, A.L.; Miller, Richard F. 2005. The role of fire in structuring sagebrush habitats and bird communities. Pages 63-75 In: Saab, Victoria A.; Powell, Hugh D. W. (eds.). Fire and Avian Ecology in North America. Studies in Avian Biology No. 30. Camarillo, CA: Cooper Ornithological Society.

Marshall, K. Anna. 1995. Ribes montigenum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

McArthur and Stevens. 2009. Composite Shrubs. In: S.B. Monsen, R. Stevens, and N.L. Shaw [compilers]. Restoring western ranges and wildlands. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. General Technical Report RMRSGTR-136-vol-2. p. 493-537.

Miller, M., Belnap, J., Beatty, S., Reynolds, R. (2006). Performance of Bromus tectorum L. in Relation to Soil Properties, Water Additions, and Chemical Amendments in Calcareous Soils of Southeastern Utah, USA. Canyonlands Research. 288. 10.1007/s11104-006-0058-4.

National Wildlife Federation (NWF). 2022. Sagebrush Steppe. Retrieved from: https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Threats-to-Wildlife/Climate-Change/Habitats/Sagebrush-Steppe.

Tom H. Oliver, Matthew S. Heard, Nick J.B. Isaac, David B. Roy, Deborah Procter, Felix Eigenbrod, Rob Freckleton, Andy Hector, C. David L. Orme, Owen L. Petchey, Vânia Proença, David Raffaelli, K. Blake Suttle, Georgina M. Mace, Berta Martín-López, Ben A. Woodcock, James M. Bullock. Biodiversity and Resilience of Ecosystem Functions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Volume 30, Issue 11, 2015.

Rodhouse TJ, Irvine KM and Bowersock L (2020) Post-Fire Vegetation Response in a Repeatedly Burned Low-Elevation Sagebrush Steppe Protected Area Provides Insights About Resilience and Invasion Resistance. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8:584726.

Rosentreter, Roger. 2005. Sagebrush identification, ecology, and palatability relative to sage-grouse. In: Shaw, Nancy L.; Pellant, Mike; Monsen, Stephen B., eds. Sage-grouse habitat restoration symposium proceedings; 2001 June 4-7; Boise, ID. Proc. RMRS-P-38. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 3-16