Ecological dynamics

Historically, this ecological site was part of a vast forested landscape with processes and functions directly connected to the highly dynamic nature of the Mississippi River (Gardiner and Oliver, 2005). Widespread changes to the landscape occurred long before any intensive studies of the historic natural communities were conducted. Accordingly, reference conditions of this ecological site are still under review. Although knowledge and interpretation of reference conditions are currently incomplete, observations and forest research over the past century have provided information on species presence, suitability, and productivity of important forest resources on some soils of this site. Their presence, management, and sustainability form the basis of the “perceived” reference state for the site.

Putnam and Bull (1932), and later Putnam (1951), characterized their “white oaks – red oaks – other hardwoods” cover type as most commonly occurring on high loamy ridges of second bottoms and old terraces. Many of the tree species listed in that cover type were later associated in manuscripts and other documents (e.g., USDA-SCS, 1959; USDA-SCS, 1968) as trees that commonly grow on or are adapted to the soils of this site. Important or key species comprising the type include swamp chestnut oak, white oak (Quercus alba), cherrybark oak, Shumard’s oak, southern red oak (Q. falcata), white ash (Fraxinus americana), hickory, blackgum, and winged elm (Putnam, 1951). Additional forest associates that are important components in some locations include sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), water oak, willow oak (Q. phellos), and American elm (Ulmus americana) (Eyre, 1980; USDA-SCS, 1968). Putnam (1951) added that this association produces some of the highest valued species and products among the southern bottomland forest types.

Putnam’s white oaks – red oaks – other hardwoods type was later absorbed into more broadly accepted forest types such as the swamp chestnut oak – cherrybark oak type (Society of American Foresters, SAF, Type No. 91; Eyre, 1980) or simply renamed the red oak – white oak – mixed species association (see Meadows and Stanturf, 1997). The diversity of tree species and other community associates are reportedly high for this system (NatureServe, 2020). Meadows and Stanturf (1997) regards this forest association as a late sere in the succession of southern bottomland forests, whereas others consider it a climax community (e.g., Eyre, 1980; Hodges, 1997).

The forest type predicted for this site was independently corroborated by colleagues in Missouri during early ecological site efforts in that state. They described this productive site as supporting a cherrybark oak – swamp chestnut oak association (see Community 1.1). Additional components observed included Shumard’s oak, bitternut hickory, and American elm. The understory was characterized as being “better developed” than adjoining wetter areas with a ground layer that supported a dense and diverse covering of herbaceous species, particularly sedges.

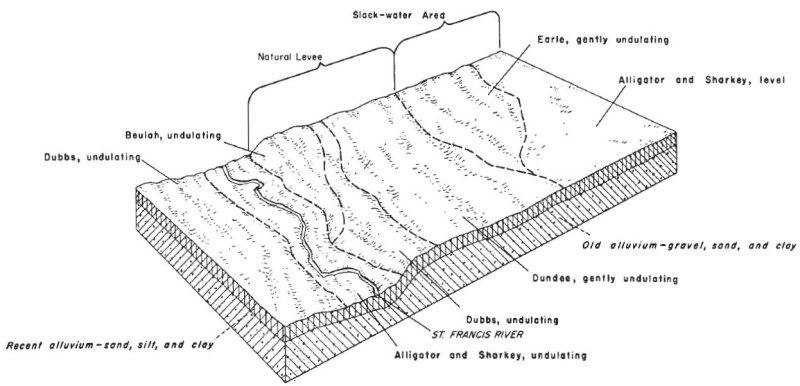

It is hypothesized that the higher elevations of this site occasionally flooded, perhaps once every 5 to 10 years with most surface water resulting from precipitation and sheet flow across the landscape (Doug Wallace, personal communication). This site is in association with wetter, lower elevation sites including remnant outwash channels. Juxtaposed to the wetter positions, the better drained, elevated position of this site create an incredibly rich medium for plant growth and production.

Predicting or anticipating a precise forest association (e.g., the perceived reference community) to occur in every location of this site is unlikely given the productivity of the soils coupled with differing ecological sites occurring in association. Klimas et al. (2013) warned that species composition of upland forests on Pleistocene terraces can vary widely depending on local soils and drainage conditions. Components and/or variants of other forest types such as the sweetgum – red oaks and the elm – ash – sugarberry associations (see Meadows and Stanturf, 1997 for brief descriptions) may converge on this site forming complex species patterns (Hodges, 1995). Such complexities may also be due to former land use histories in addition to contrasting soil-site environments occurring in proximity.

Overall, forest cover on this site is minor compared to other uses. Most areas have been cleared and are used extensively for row crop production. Some areas have been land leveled with soil surface cuts of up to 3 feet to meet irrigation needs. A secondary use on this site is pasturage.

Following this narrative, a “provisional” state and transition model is provided that includes the “perceived” reference state and several alternative (or altered) vegetation states that have been observed and/or projected for this ecological site. This model is based on limited inventories, literature, expert knowledge, and interpretations. Plant communities may differ from one location to the next depending on the severity of local land use activities and rates of deposition. Depending on objectives, the reference plant community may not necessarily be the management goal.

The environmental and biological characteristics of this site are complex and dynamic. As such, the following diagram suggests pathways that the vegetation on this site might take, given that the modal concepts of climate and soils are met within an area of interest. Specific locations with unique soils and disturbance histories may have alternate pathways that are not represented in the model. This information is intended to show the possibilities within a given set of circumstances and represents the initial steps toward developing a defensible description and model. The model and associated information are subject to change as knowledge increases and new information is garnered. This is an iterative process. Most importantly, local and/or state professional guidance should always be sought before pursuing a treatment scenario.

State 1

Reference: Loamy Interfluve Forest

Removal of or extensive modification to the historic natural communities in the St. Francis Basin occurred long before thorough studies and investigations were conducted. Furthermore, drainage patterns and surface characteristics of the landscape have since been heavily altered. Great variability is likely to occur throughout the distribution of most if not all ecological sites. Local soils and hydrologic regimes will have been influenced by the environment they occur within including former land use histories. Such complexity across the area will likely result in much variability in vegetation composition and structure of local environments (Stanturf et al., 2001).

Accordingly, reference conditions for this site have yet to be confirmed, but recent observations and published accounts have provided a convincing context from which to guide future efforts. Once assigned or identified and verified, the reference community will not represent the pre-settlement forest community, but it should identify an assemblage of naturally occurring species that reflects and contributes to regional biodiversity and local ecological dynamics. Implicated in the latter is that the “local” geomorphic features and drainage patterns of this soil-site environment should not have been drastically altered or removed (e.g., land leveled).

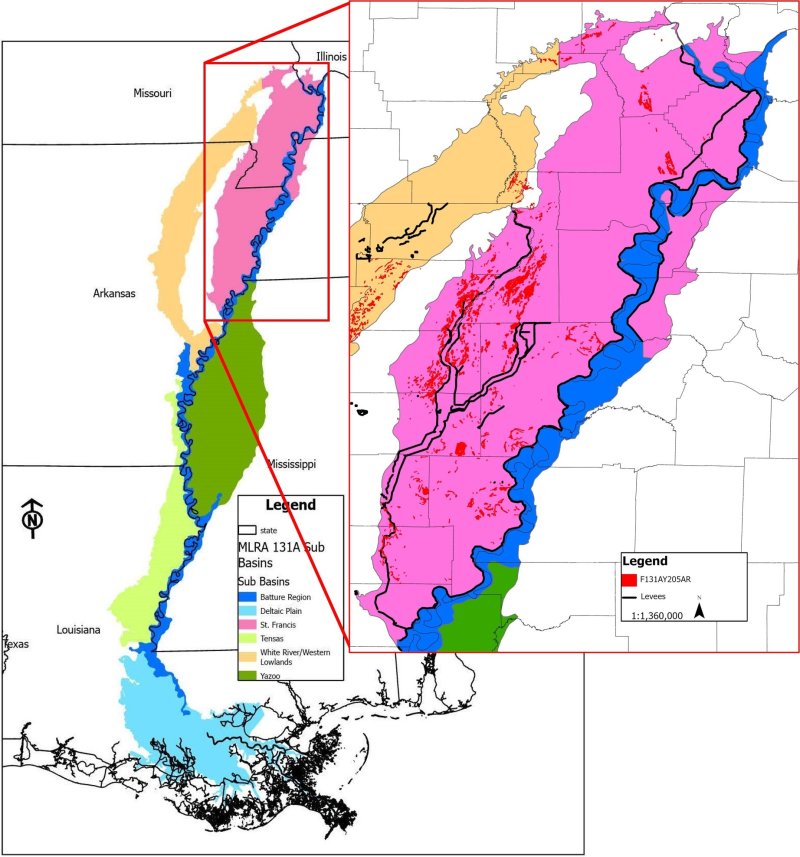

The name of this state (currently assigned the Reference State and warrants verification) is an interpretation based on Klimas et al. (2013) and bolstered from observations by Missouri colleagues. The productive loamy soils of this site have moderate extent across the surfaces of the Late Pleistocene valley trains in southeastern Missouri and northeastern Arkansas. Observations and literature accounts published to date are combined, herein.

The current state and transition model does not have a return or transition pathway from the altered states back to reference conditions. Former land uses (alternate states) that result in altered soil structure (e.g., compaction and increased bulk densities), lower soil organic matter content, altered fertility, and smaller available rooting volume can reduce woodland site productivity by 10 to 20 percent for some species(Groninger et al., 1999) and may result in high seedling mortality. Attempts to establish reference conditions under these soil-site constraints could result in poor establishment and response, colonization by undesirable taxa, or failure. These soil-site impacts, however, can be ameliorated through various “afforestation” techniques such as plow pan breakup (subsoil or deep plowing), fertilization, and fallowing fields before stand establishment (Emile Gardiner, USFS Research Forester, personal communication). State 6 (Forest Recovery) is representative of forest establishment and growth on locations where soil compaction and reduction of nutrients have occurred. Once a previously affected location has recovered its site potential, transition to the reference state may be possible. Realistically, it may not always be possible to return to a “perceived” reference state from a former altered condition. While planting and establishing trees appropriate for a site may be possible, achieving restoration of the understory and other system functions present challenges that may never be realized (Stanturf et al., 2001; Flinn and Vellend, 2005). That potential transition is still under review and is currently not shown or addressed in the state and transition model.

Community 1.1

Cherrybark Oak - Swamp Chestnut Oak Braided Interfluve Forest

Based on available information, this community is “provisionally” considered to be representative of reference conditions for this ecological site. This community was first recognized by Putnam and Bull (1932) as loamy ridge oaks and later described by Putnam (1951) as occurring “…on the most matured terrace soils.” Their early descriptions were later combined into a singular forest type: swamp chestnut oak – cherrybark oak (SAF Type No. 91; Eyre, 1980). During early ecological site inventories, colleagues in Missouri described the “loamy braided terrace” soils as supporting a variant of the communities referenced and described by the preceding authors. The association they “typed” during their investigations was the cherrybark oak – swamp chestnut oak / burningbush (Euonymus atropurpureus) / eastern waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum) – sedge (Carex spp.) Loamy Braided Terrace Forest (Doug Wallace, personal communication). Independent investigations conducted by Klimas et al. (2013) in Arkansas reported similar dominant canopy species occurring on higher interfluves of Pleistocene outwash terraces.

The dominant canopy species reported on this site in Missouri and Arkansas include cherrybark oak, swamp chestnut oak, water oak, Shumard’s oak, bitternut hickory, pecan, American elm, and sugarberry (Klimas et al., 2013; Doug Wallace, personal communication). Eyre (1980) provided a much expanded list of possible associates of this cover type including willow oak (Quercus phellos), white oak (Q. alba), bottomland or Delta post oak (Q. similis), post oak (Q. stellata), sweetgum, green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), white ash (F. americana), shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), shellbark hickory (C. laciniosa), mockernut hickory (C. tomentosa), and blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica). The understory is generally well represented with subordinate trees and shrubs that include pawpaw (Asimina triloba), American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), flowering dogwood (Cornus floridana), possumhaw (Ilex decidua), devil’s walkingstick (Aralia spinosa), eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis), and American holly (Ilex opaca). Ground cover is reportedly dense and diverse with herbaceous components consisting of sedges (Carex spp.) and dense growths of the fabled giant cane (Arundinaria gigantea) within some canopy openings. Vines can be prevalent in the understory and may be represented by eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), and Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) (NatureServe, 2020).

Broadfoot (1976) provided a list of species that are favored in management and that occur frequently or occasionally on one of the principal soils of this site, the moderately well drained Askew soils. The following are species favored in management and that frequently occur on Askew soils (per Broadfoot, 1976) with estimated site index ranges (tree height in feet at 50 years except cottonwood which is 30 years) in parentheses: cherrybark oak (95 to 115), water oak (90 to 110), willow oak (90 to 110), and sweetgum (90 to 110). The following are site index ranges of species favored in management that occasionally occur on Askew soils: green ash (70 to 90), eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides, 90 to 110), hickory (75 to 95), Nuttall oak (90 to 110), Shumard oak (95 to 115), swamp chestnut oak (80 to 100), pecan (Carya illinoinensis, 85 to 105), and American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis, 100 to 120).

Dominant plant species

-

cherrybark oak (Quercus pagoda), tree

-

swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii), tree

-

water oak (Quercus nigra), tree

-

Shumard's oak (Quercus shumardii), tree

-

bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), tree

-

pecan (Carya illinoinensis), tree

-

American elm (Ulmus americana), tree

-

sugarberry (Celtis laevigata), tree

-

pawpaw (Asimina triloba), shrub

-

possumhaw (Ilex decidua), shrub

-

giant cane (Arundinaria gigantea), shrub

-

eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), shrub

-

trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), shrub

-

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), shrub

-

sedge (Carex), grass

State 2

Commercial Forestland

This state consists of two very different community phases and management approaches. Community Phase 2.1 represents forest management and production on this site. A distinguishing feature of this phase is the level of management intensity designed to maximize merchantable goals. Various silvicultural methods are available for selection, and these are generally grouped into even-aged (e.g., clearcutting, seed-tree, and shelterwood) and uneven-aged (e.g., single tree, diameter-limit, basal area, and group selection) approaches (Meadows and Stanturf, 1997). Depending on the method selected, different structural and compositional characteristics of the stand may result. Removal and control of community associates are typically a critical element of production goals. These actions may result in different community or “management phases” (and possibly alternate states) depending on the methods used and desired results. Finding the appropriate approach for a given stand and environment necessitates close consultation with trained, experienced, and knowledgeable forestry professionals. If there is a desire to proceed with this state, it is strongly urged and advised that professional guidance be obtained and a well-designed silvicultural plan developed in advance of any work conducted.

Community Phase 2.2 represents conditions of many stands that have incurred indiscriminate timber harvests (e.g., heavy cutting or diameter-limit harvests of select species) and opportunistic regrowth following such harvests (i.e., no management at any period). Some stands may continue to support a few desirable species and quality stems, but in many instances, affected stands will be comprised of mostly shade tolerant species or trees of desirable species that fail to meet their maximum potential. (Because of the intensive management required to rehabilitate affected stands, this community phase may warrant elevation to a standalone state. This should be considered in future iterations of this site’s development.)

This site is well suited for forest production with very few limitations. Where this site occurs in complex or contact with wetter ecological sites, seasonal wetness and periods of heavy precipitation can impose some limitations on heavy equipment usage. If possible, equipment operations are best conducted during drier periods of the year, which minimizes soil damage, erosion, and helps to maintain productivity. Perhaps the most significant limitation is the inherent productivity of the soils. This can contribute to intense plant competition and even exclusion of targeted (desirable) trees if management of the stand becomes relaxed or is not pursued.

An important caveat of this state is its representation of forest conditions that have retained full site production potential. Currently, transitional pathways to this state originate from another forested state (State 1), only. Former land uses (alternate states) that result in soil compaction (increased bulk densities), lower soil organic matter content, altered fertility, and smaller available rooting volume can reduce forest site productivity by 10 to 20 percent, if not more, for some species (Groninger et al., 1999). These impacts are perhaps most pronounced on poorly drained, clayey soils. The higher and better drained loamy soils of this site likely will not have the deleterious impacts to tree productivity on the same scale as the latter. Still, the combined effects of intensive, long-term cultivation (e.g., moderately compacted soils, plow pan presence, reduced fertility, and low organic matter content) on the well-developed soils of this site can lower site productivity for some species (see Baker and Broadfoot, 1979). These impacts, however, can be ameliorated through various “afforestation” techniques such as plow pan breakup (subsoil or deep plowing), fertilization, and fallowing fields before stand establishment (Emile Gardiner, USFS Research Forester, personal communication with Rachel Stout Evans, contributing author). State 6 (Forest Recovery) is representative of forest establishment and growth on locations where soil compaction and reduction of nutrients have occurred. Once a previously affected location has recovered its site potential, transition to this state may be possible. That potential transition is still under review and is currently not shown or addressed in the state and transition model.

Community 2.1

Forest Management

Prescribing a silvicultural system for a given stand depends on species composition; long term production and postproduction goals; and the presence and abundance of advance regeneration (i.e., the presence of seedlings and saplings of the desired species). The canopy trees listed in State 1 as “favored in management” are all production options on this site ranging from single species plantations to complex multi-species stands. (Species favored in management are indicated below under the "Dominant tree species" section for convenience.)

Establishing and maintaining oaks on bottomland sites may be preferred given the multiple values they provide (e.g., timber and wildlife). However, maintaining that component beyond a single rotation (or harvest) may be the most challenging. Creating conditions that promote oak persistence in future stands require a sufficient advance regeneration component. Ensuring that this future crop is established will require close adherence to a well-designed silvicultural plan, which requires programmatic intermediate operations (e.g., improvement cuttings, thinnings, and other partial cuttings). An even-aged silvicultural system that utilizes the clearcutting regeneration method along with brush management to reduce subsequent competition is typically the advocated approach when harvesting bottomland oak stands (Johnson and Shropshire, 1983; Clatterbuck and Meadows, 1993; Hodges, 1995; Meadows and Stanturf, 1997; Oliver et al., 2005).

Except pecan, the remaining trees that are favored in management are light-seeded species. Various silvicultural systems may be implemented to promote production of these species including even-aged and group selection (uneven-aged) approaches (see Meadows and Stanturf, 1997).

Community 2.2

Non-managed/High-graded

This forest community is directly influenced by former harvesting practices that include repeated single-tree selection and/or diameter-limit harvests with no additional management activities (e.g., brush management, competitor control, etc.). These practices typically target the highest quality trees of the most desirable species. The result is usually an expansion and in-filling of shade tolerant subcanopy trees. Over time, this practice will lead to a predominantly shade tolerant community that may be comprised of American elm, winged elm, hickory, blackgum, boxelder (Acer negundo), American hornbeam, roughleaf dogwood, possumhaw, and possibly sugarberry, although reportedly rare on ridges of older alluvium (Putnam et al., 1960).

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Heavy cutting of the stand that removes the desired species (typically shade intolerant species) of sufficient diameters followed by no management of the residual stand. This pathway also includes repeated single-tree harvests (e.g., diameter-limit cuts) that removes the desired species followed by no management of the residual stand. The resulting stand is typically comprised of shade tolerant species with low commercial value.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Intensive management will be required to push a shade tolerant community into a more commercially desirable and viable system. Actions will likely require a complete clearcut of the stand followed by repeated brush and competitor control (chemical and mechanical). If there is a lack of seed source, artificial regeneration will likely be required to reintroduce heavy-seeded species (e.g., oaks). Continual competitor control will be needed.

State 3

Cropland

This state is representative of the dominant land use activity on this ecological site, agriculture production. The dominant crops grown on this site are cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), corn (Zea mays), soybeans (Glycine max) and wheat (Triticum aestivum) (Snipes et al., 2005). Minor crops, such as some specialty crops (e.g., fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts such as pecans), may be grown locally.

The soils of this site are well suited to agriculture production. Tilth is reportedly good with a surface layer that is very friable and easily tilled and managed over a wide range of moisture content. Management concerns are largely centered on erosion, plow pan development, soil compaction under equipment traffic, crusting and packing following heavy rain, and low organic matter content (Snipes et al., 2005; USDA-NRCS, 2006b). Snipes et al. (2005) emphasized that the organic matter content of the soils of this site typically range from 0.5 to 2.0 percent with most concentrations within to 0.9 to 1.5 percent range. Each of these factors could affect yields or impede optimum operation. Management measures to ameliorate some of these issues may include implementing a conservation tillage or management system and subsoiling to breakup plow pans (USDA-NRCS, 2006b). Major components that producers generally develop and plan are proper selection of crop cultivar, pest control, cropping system, tillage methods, nutrient management, and water management (Snipes et al., 2005). Key practices of some cropping systems often include two or more crops grown in a multiyear rotation, which has been documented to disrupt pest cycles. Leaving crop residue on the surface can help to maintain tilth, fertility, and organic matter content – all critical elements of soil quality and health. For monoculture cropping systems, the implementation of well-designed pest and nutrient management systems are imperative (Pringle et al., 2017). (For assistance, interested parties are advised to visit their local NRCS Field Office.)

Three separate management phases comprise this state: Conservation Management (3.1), Transitional Conservation Management (3.2), and Conventional Management (3.3). The three phases consist of varying tillage methods and approaches to soil health management systems.

Community 3.1

Conservation Management

This cropland phase utilizes long term, continuous conservation management systems that include reduced till and cover crops; no-till with cover crops; crop residue retention; and perennial cropping systems. The guiding principles of this system are minimizing soil disturbance and maximizing soil cover, biodiversity, and the presence of living roots. Implementing diverse crop rotations while maintaining these principles can lend to the development of an integrated pest management plan and contribute to overall system resilience.

Of caution, the above-ground crop growth or yields may not be the best tracking mechanism for assessing the efficacy or presence of this management phase. Indicators of these systems are generally determined via soil-site assessments with outcomes that may include enhanced soil aggregate stability, increased soil biological activity, higher organic matter content, and improved water holding capacity and infiltration rates while also alleviating soil compaction and reducing runoff and erosion (Chessman et al., 2019). Additional advantages to this system that have been noted by some producers are reductions in fuel and labor costs and less wear and tear on machinery and equipment.

There are challenges to this management system, especially in situations where tillage may be considered and/or needed to repair weather damage or other detrimental impacts. Implementation of conventional tillage even after long term conservation practices (e.g., no-till) can reset the affected area back to a conventional cropping system. However, those changes can be reversed and a return to a conservation management system is achievable.

Critical conservation practices associated with this phase include cover crops, no-till, and reduced till as the foundational practices. Additionally, this phase may include supporting and site-specific practices to address conservation needs for a given location.

Community 3.2

Transitional Conservation Management

This cropland phase utilizes a hybrid approach that combines conventional methods with conservation practices at specific periods and under specific situations. Practices under this phase may include a combination of conventional till, reduced till, strip till, and the inclusion of cover crops. For instance, perennial crop species could be in a continuous transitional phase where conventional tillage is implemented at the time of planting followed by reduced tillage during the rotation. Planted forage crops could also be included in this phase, especially when part of a crop rotation that utilizes reduced tillage for one crop followed by conventional tillage for a succeeding crop.

The development, implementation, and refinement of nutrient and pest management plans throughout component operations are imperative. Additionally, this phase may include supporting and site-specific practices to address conservation needs for a given location.

Community 3.3

Conventional Management

This management phase is representative of conventional cropland where tillage is implemented as an annual component of the production system. As crucial elements of the system, conservation practices such as nutrient and pest management are needed to address fertility requirements and pest concerns within the crop cycle. It is important to note that this phase may develop when tillage is implemented to address damage or for other purposes while under a conservation management system (Community Phase 3.1). There could also be associated, supporting, and site-specific practices that are needed to address specific conservation needs. Specific needs may include grade stabilization structures to control gully erosion, grassed waterways to trap sediment from sheet and rill erosion, or implementing reduced till.

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Soil disturbance (tillage); reduction of soil health.

Pathway 3.1B

Community 3.1 to 3.3

Conventional tillage, seeding, and fertility management for crops.

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

No-till, cover crops, reduced till-soil health improvements.

Pathway 3.2B

Community 3.2 to 3.3

Conventional tillage, seeding, and fertility management for crops.

Pathway 3.3A

Community 3.3 to 3.2

Reduced till, no-till, and cover crops with soil health improvements as a goal.

State 4

Land Formed Cropland

This gently sloping to undulating ecological site typically adjoins nearly level to level landscapes. It is bordered by soils of varying textures and drainage characteristics. Accordingly, inconsistencies in wetness, ease of operation, and production or yields may occur across a cropped location. An increasingly common practice on this site consists of land forming or leveling surface irregularities into a predetermined and engineered, uniform slope. This practice removes the drier and higher features of this site, which are then used to fill wetter and lower positions (e.g., depressions or swales) across the targeted area. Advantages of land leveling may include reduced hazards of erosion and runoff rates, improved surface drainage, and enhanced distribution and conservation of irrigation water. Disadvantages of the practice is a churning of various surface and subsurface materials (former soil horizons) that no longer occur in a predictable or regular pattern. Organic matter content in the surface layer is generally low, and the surface tends to crust and pack after heavy rains (USDA-NRCS, 2006b). One potential hazard that appears to be emerging in some areas is an effective management of surface water runoff. As both irrigated and stormwater runs off leveled fields at uniform rates, surface water tends to collect cumulatively and simultaneously, which places tremendous demands on local drainage networks. Without “in field” structures (natural or artificial) to stagger runoff, the downslope (or lower) ends of some fields tend to back flood thereby contributing to more flooding overall in local watersheds (personal observations).

Immediately following land leveling, the constituent elements of soil health are likely to be absent. In some areas, producers have initiated practices such as applying organic residues (e.g., poultry litter) or growing rice crops for one to two years to rapidly boost fertility and introduce organic matter (via rice biomass) in the surface layer. Over time, the full complement of the management (or community) phases of State 3 may be possible on land leveled fields. They are not repeated or indicated here.

Currently, this state serves as an endpoint in the state and transition model because the ability to predict vegetation response when transitioning to a different state is no longer possible without soil-site investigations for each area of interest. The former soils of this ecological site, including surface and subsurface horizons, will have been redistributed as particles among other former soils.

Community 4.1

Land Leveled Cropland

Some of the crop species and management practices indicated and discussed in State 3 (including all three management phases) may be suitable for establishing on land leveled areas that once supported the soils of this site. However, the type of crops suited for newly leveled areas may ultimately depend on the prevailing soil particle-size distribution and internal drainage characteristics. Former studies on precision leveled fields have noted variabilities and inconsistencies in soil particle-size distributions, bulk density, soil biological properties, and nutrients (Brye et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2003; Brye et al., 2006). Management concerns for this phase may consist of restricted permeability, low organic matter content, and crusting and packing (USDA-NRCS, 2006b). These impacts may be improved by implementing conservation tillage, cover crops, retaining crop residue, and nutrient and pest management strategies.

State 5

Pastureland/Grassland

This state is representative of areas that have been converted to and maintained in pasture or grassland. The soils of this site are generally considered well suited to most commonly grown perennial forage species. Available water capacity is moderate to high, and production on this site is generally high when areas are adequately fertilized and properly managed. The very strongly to moderately acid reactions of these soils usually require lime for many forage species.

Given that this ecological site adjoins lower, wetter sites, some forage operations may utilize the higher elevations of this site as a protected area. This site may be suitable for the storage of harvested forage or holding of livestock when wet or flooded conditions occur on lower areas.

Establishing an effective pasture management program can help minimize degradation of the site and assist in maintaining growth of desired forage. An effective pasture management program includes selecting well-adapted grass and/or legume species that will grow and establish rapidly; maintaining proper soil pH and fertility levels; using controlled grazing practices; mowing at proper timing and stage of maturity; allowing new seedings to become well established before use; and renovating pastures when needed (Rhodes et al., 2005; Green et al., 2006).

This state consists of four community phases that represent a range of forage management options and pasture and hayland condition scenarios. Options range from establishing a forage monoculture for haying to a broad mixture of forage species for production and grazing. It is strongly advised that consultation with local NRCS Service Centers be sought when assistance is needed in developing management recommendations or prescribed grazing practices.

Community 5.1

Monoculture Grassland

This phase is mainly characterized by planting forage species for hay production. Forage plantings generally consist of a single grass species. Native and non-native forage species can be seeded. Forage is usually harvested as hay or haylage, although grazing may occur periodically. These sites are highly productive for forage and can provide ecological benefits to control soil erosion. Allowing for adequate rest and regrowth of desired species is required to maintain productivity. Maintenance of monoculture stands also requires control of unwanted species, which will require pest and nutrient management.

Generally, the application of fertilizer and lime is needed to establish and maintain improved desirable pastures. Exceptions do occur for bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum) and common bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), which can be sustained under natural fertility and pH levels. Introduced grasses, such as hybrid bermudagrass, require a higher level of sustained fertility, pH above 6.0, and good surface drainage to persist. An additional measure to aid production may include prescribed grazing. Implementing limited and monitored grazing can promote deeper root penetration of grasses with the added benefit of greater nutrient and moisture uptake. This synergistic approach can lead to increased production of and may sustain desirable forages.

Conservation practices should include prescribed grazing, or forage harvest management, nutrient and pest management, and potentially other site-specific practices.

Community 5.2

Mixed Species System

This community is characterized by mixed species composition of grasses and legumes. Components of this forage system are either planted or they established naturally. Typically, perennial warm-season grasses are the foundation of the stand that are periodically overseeded with adapted cool-season forages. The latter creates an added benefit of extending the grazing season. This community phase can be highly productive for grazing and haying operations and can provide beneficial habitat for some wildlife species.

Maintenance of grass stands also requires a series of management practices such as prescribed grazing, brush management, pest management, and nutrient management to maintain production of the desired species. Prescribed grazing includes maintaining proper grazing or forage heights, timing, and stocking rates. Supporting or facilitating practices such as fences, water lines, and watering facilities could be part of the system that maintains this phase.

Community 5.3

Mixed Species, Non-seeded

This community is characterized by a mixture of native and naturalized non-native species. Forage is usually grazed and/or harvested as stored forage, hay or haylage. Common established species may include tall fescue, Bermudagrass, bahiagrass, dallisgrass, and carpetgrass (Axonopus sp.).

Stands are generally productive, and forage and grazing management can maintain the community. Healthy stands provide additional benefits by protecting soils from excessive runoff and erosion. However, a common peril associated with this phase is overgrazing, which lowers production and favors less palatable weedy species, especially in areas where livestock congregate. Proper stocking rates or grazing systems that allow for adequate rest and plant regrowth are required to maintain productivity. When forage species are afforded adequate recovery time between grazing intervals, they develop deeper root systems and greater leaf area. Conversely, when plants are not allowed to adequately recover, root development will be restricted leading to lower forage and biomass production. Additionally, maintenance of grass stands requires implementing pest management practices to control unwanted weedy and woody species.

Community 5.4

Early Woody Succession

This community is characterized by a diverse composition of grasses and forbs with an increasing presence of woody species (both native and non-native) that are immature and of low stature. Woody species grow quickly on this site and can be difficult and expensive to control. One potentially problematic species may be honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos). Putnam (1951) reported honeylocust as being common on old pastures, and the species can be difficult to remove once established. Management to transition this phase to other forage communities of this state is still possible without excessive inputs and effort, particularly if stem diameters remain below 2 inches and are widely scattered (e.g., a density of less than 100 stems per acre). However, if diameters become greater than 3 inches and densities exceed 300 stems per acre, far more investment, effort, and inputs will be required. If brush management measures are not undertaken, the plant community will transition to the Ruderal/Opportunistic Regrowth (Community Phase 6.1) of State 6.

Of note, this community phase is often very beneficial habitat for some wildlife species, especially a specific guild of resident and Neotropical migratory bird species that depend on old field to young tree stand habitats.

Pathway 5.1A

Community 5.1 to 5.2

Seeding and/or management for desired species composition.

Pathway 5.1B

Community 5.1 to 5.3

Species management without overseeding.

Pathway 5.2A

Community 5.2 to 5.1

Seeding, fertilizing, management/removal of undesirable species.

Pathway 5.2B

Community 5.2 to 5.3

Species management without overseeding

Pathway 5.3A

Community 5.3 to 5.1

Seeding, fertilizing, management/removal of undesirable species.

Pathway 5.3B

Community 5.3 to 5.2

Seeding and/or management for desired species composition.

Pathway 5.3C

Community 5.3 to 5.4

Lack of disturbance; no (infrequent) mowing, herbivory, or brush management; natural succession of woody species.

Pathway 5.4A

Community 5.4 to 5.3

Brush management/removal of unwanted species.

State 6

Forest Recovery

This state is representative of forest recovery in areas that were once under former intensive land use such as long-term row crop cultivation. Characteristics that distinguish this state from other forest states on this site include a suite of soil-site properties that reportedly affect tree growth such as higher soil bulk density due to compaction, presence of a plow pan, lower organic matter content, and reduced fertility (Baker and Broadfoot, 1979; Groninger et al., 1999). Two community phases are provisionally recognized for this state. Community Phase 6.1 represents natural colonization of tree and shrub species without management. Community Phase 6.2 is representative of intentional forest establishment by artificial regeneration or planting.

For Community Phase 6.2, determining the objectives and goals of the future stand is imperative to increase the probability of successful establishment and production of the afforested area. These decisions will ultimately determine the species to be established, preparation requirements, planting density, and post-planting operations (e.g., competitor control, future improvement cuttings and thinnings, regeneration methods, and overall stand health). Since each area targeted for afforestation may have unique or different land use histories, having a clear understanding of the soil-site conditions are essential. Some areas may necessitate a series of soil improvement actions prior to planting. These actions may include subsoiling or deep plowing to breakup plow pans and fertilizing the targeted area. An additional option is to allow the area to undergo fallowing for a predetermined period (Community Phase 6.1) to potentially increase soil organic matter content, enhance soil aggregate stability, increase soil biological activity, and improve water holding capacity and infiltration rates. Controlling competing vegetation (chemical and mechanical treatment) will most likely be critical. Post-planting operations and maintenance of the stand can enhance survival, future development, and achieve goals and objectives (see Gardiner et al., 2002).

Finding the appropriate approach for a given environment necessitates close consultation with trained, experienced, and knowledgeable forestry professionals. If there is a desire to proceed with this state, it is strongly urged and advised that professional guidance be obtained and a well-designed afforestation and silvicultural plan developed in advance of any work conducted. For an exceptional review and summarization of the afforestation literature, techniques, and practices within the Southern Mississippi River Alluvium, interested parties are directed to Gardiner et al. (2002).

Community 6.1

Ruderal/Opportunistic Regrowth

This community phase is representative of former working lands (e.g., cropland and possibly high concentration areas of former pastureland) that have fallowed and subsequently undergone natural colonization by vegetation. A profusion of growth will likely initiate within five to ten years of becoming idle – one that typically includes grasses, forbs, woody seedlings and shrubs, and an increasing presence and covering of vines. Initial colonization may be dominant in annuals followed by a shift to perennial vegetation. Shrubs and tree seedlings may appear very early following abandonment, however the rate of colonization and period to stand establishment likely depends on the proximity of established mature stands (Battaglia et al., 1995; Battaglia et al., 2002). If established stands consisting of light-seeded species adjoin fallow fields, colonizing tree species will likely be comprised of those taxa (e.g., green ash, elm, sycamore, and cottonwood) (Allen, 1990; Stanturf et al., 2001). Some areas may be far removed from established forest stands. Under this scenario, establishment of woody species (especially overstory tree species) may be very slow, and years may be required before stand establishment is reached (Battaglia et al., 1995; Allen, 1997). In fact, natural colonization by some species may be delayed indefinitely with some stands or areas being understocked (Allen, 1997; Battaglia et al., 2002; Groninger, 2005). Heavy-seeded species like oaks and hickory may not have an opportunity to colonize available areas due to distance and lack of a dependable dispersing agent (e.g., wildlife and water). For those areas close to a viable seed source, oaks may be a component of the developing stand, although in the early stages of stand development oaks are likely to be a minor component (Meadows, 1993). Non-native invasive species may become part of the developing stand given the proliferation of exotic plant species over the past century.

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to predict the future composition and structure of an abandoned field on this site. Many different environmental factors will influence initial colonization and development trajectories. The following projections are simply based on native plant species reported to occur on the soils of this site. As the young stand matures and eventually enters the stem exclusion stage (crown or canopy closure), composition may include American elm, green ash, eastern cottonwood, American sycamore, sweetgum, and American hornbeam. Oaks that may occur in the young stand include cherrybark, swamp chestnut, water, willow, and possibly Nuttall but these will likely be rare or uncommon components, if present at all. Problematic non-native species that may occur include Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), and possibly Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana). Vines common in the young, developing stand may include greenbrier (Smilax spp.), eastern poison ivy, and trumpet creeper. As the stand matures decades into the future and the overstory stratifies (i.e., the understory reinitiation stage), shade tolerant species may rise to prominence in the stand.

Community 6.2

Afforestation

This community phase is representative of areas planted in tree species that are suited for and favored in management on this ecological site. Preparation of this phase may be initiated immediately following a former landuse activity (e.g., State 3) or it may be started following a fallow period (Community Phase 6.1). If afforestation is initiated immediately following years of conventional tillage without soil-site preparation and improvement efforts, potential productivity of the targeted area could be less than optimal if soil compaction, plow pan presence, degraded fertility, and/or depleted organic matter content are existing factors (Baker and Broadfoot, 1979; Groninger et al., 1999; Gardiner et al., 2002).

Over the years, various afforestation innovations have increased the likelihood of success in addition to soil-site amelioration such as planting large, high-quality seedlings with well-developed root systems in an appropriate cover crop (Dey et al., 2010); interplanting seedlings within a fast-growing pioneer species nurse crop (e.g., cottonwood) (Gardiner et al., 2001); and planting companionable species combinations for mixed species stands (Lockhart et al., 2008). The cover crop and nurse crop approaches reportedly help to control rapid overtopping and crowding by competing vegetation and wildlife herbivory (Dey et al., 2010). Finding the appropriate strategy for a given location requires matching the species to the local hydrologic and soil-site environment; determining short- and long-term objectives and goals; and implementing the appropriate management actions at the required intervals.

Several species that frequently occur and favored in management (see State 1) are likely appropriate for planting on this ecological site. However, Broadfoot (1976) listed a much narrower group of hardwoods suitable for planting on one of the soils of this site, Askew soils, and they are sweetgum, green ash, eastern cottonwood, Nuttall oak, Shumard’s oak, and American sycamore. Although not included in Broadfoot’s list of trees to plant, extremely important components such as cherrybark oak and water oak are included as naturally occurring species on these higher and drier “ridge soils” and may warrant consideration (Putnam, 1951; Eyre, 1980).

Pathway 6.1A

Community 6.1 to 6.2

Remove undesirable competitors; final soil preparation; establish site-appropriate species (favored in management).

State 7

Conservation (Herbaceous)

This state is representative of the range of conservation actions that may be implemented and established on this ecological site. Apart from planting trees and managing for forest, one may elect to establish native herbaceous species and manage for predominantly a native grassland; a complex mixture of native grasses and forbs; or a pollinator planting whereby native forbs dominate the mix. In each of these options, it is strongly advised (possibly a programmatic requirement) that the species comprising the planting or seed mix consist of spring, summer, and fall flowering species. Depending on goals and objectives, various conservation programs and practices may be available. For additional information and assistance, please contact or visit the local NRCS Field Office.

Community 7.1

Pollinator Planting/Native Grasses

This community phase represents the establishment of native forbs or wildflowers for pollinator habitat or native grasses. The seed mix for planting may be quite varied depending on objectives and goals. Ideally, the mix includes a wide range of species that flower at various times of the growing season (spring, summer, and fall). Plant species in some pollinator mixes may include but are not limited to beebalm (Monarda spp.), milkweeds (Asclepias spp.), beardtongue (Penstemon spp.), vervain (Verbena spp.), various legumes such as native lespedeza (Lespedeza spp.), Illinois bundleflower (Desmanthus illinoensis), partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata), and a broad assortment of composites such as asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), tickseed (Coreopsis spp.), blazing star (Liatris spp.), coneflower (Rudbeckia spp.), sunflower (Helianthus spp.) among many others. If goals and objectives are to establish native grasses within a forb mix or in a grass-dominant stand, species suitable for planting may include big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans).

Key to the establishment of this phase is initial preparation, seeding rate, planting period, follow-up treatment, and maintenance of the planting. The selection of species to establish on any given area may ultimately depend on size and conditions of the location where the planting will occur, landowner/manager goals and objectives, and the advice and knowledge of the conservation practitioner.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Stand composition is heavily altered and managed to favor select species for production (Community Phase 2.1). This transitional pathway also includes heavy timber cutting and/or repeated partial harvests (high-grading) leading to Community Phase 2.2.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Actions include mechanical removal of vegetation and stumps; herbicide treatment of residual plants; and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 5

Actions include mechanical removal of vegetation and stumps; herbicide treatment of residual plants; seedbed preparation; and establishment of desired forage.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 1

This transition represents a return to perceived reference conditions and involves the re-establishment of missing species; the control/removal of exotic species (herbicide and mechanical); stand improvement practices that favors a return of more shade intolerant components.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 3

Actions include mechanical removal of vegetation and stumps; herbicide treatment of residual plants; and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

Actions include mechanical removal of vegetation and stumps; herbicide treatment of residual plants; seedbed preparation; and establishment of desired forage.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Precision land leveling

Transition T3B

State 3 to 5

Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); seedbed preparation; establishment of desired forage; manage for grazing

Transition T3C

State 3 to 6

Natural succession (Community 6.1) or prepare area (e.g., plow pan breakup, fertilizing, etc.) and plant tree species appropriate for site (Afforestation - Community 6.2)

Transition T3D

State 3 to 7

Establish select native species suitable for site; prepare for planting (herbicide and/or mechanical)

Transition T5A

State 5 to 3

Actions include mechanical removal of vegetation; herbicide treatment of residual plants; and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T5B

State 5 to 6

Natural succession (Community 6.1) or prepare area (e.g., plow pan breakup, fertilizing, etc.) for planting tree species appropriate for site (Afforestation - Community 6.2)

Transition T5C

State 5 to 7

Establish select native species suitable for site and prepare area for planting (herbicide and/or mechanical).

Transition T6A

State 6 to 3

Cropland establishment: vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical) and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T6B

State 6 to 5

Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); seedbed preparation; establishment of desired forage; manage for grazing

Transition T7A

State 7 to 3

Cropland establishment: vegetation removal (mechanical/chemical) and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T7B

State 7 to 5

Establish desired forage species and manage for grazing.

Transition T7C

State 7 to 6

Natural succession (Community 6.1) or prepare area (e.g., plow pan breakup, fertilizing, etc.) for planting tree species appropriate for site (Afforestation - Community 6.2).