Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R056AY094ND

Loamy

Last updated: 5/21/2025

Accessed: 10/18/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 056A–Glacial Lake Agassiz, Red River Valley

For more information on MLRAs, refer to the following web site:

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/resources/data-and-reports/major-land-resource-area-mlra

The Red River Valley of the North MLRA is an expansive and agriculturally important region consisting of 10,400,000 acres and including a portion of 25 counties in eastern North Dakota and northwestern Minnesota along with a small portion of the northeast corner (Roberts County) of South Dakota.

Although MLRA 56A is currently called the Red River Valley of the North, the landscape does not fit the common understanding of “valley” as the transition out of the Valley is very gradual in most places. The extent of the MLRA corresponds to the area covered by Glacial Lake Agassiz including lacustrine sediments, beach ridges, and deltas where rivers flowed into the glacial lake. Also included are island areas of glacial till which were surrounded by the lake waters. Some of the lacustrine deposits are very deep and some have glacial till within a few feet of the surface. The glaciolacustrine materials range from clayey to sandy.

The primary river in the MLRA is the Red River of the North flowing northward into Canada where it empties into Lake Winnipeg. The river is formed by the confluence of the Bois de Sioux River (flowing from northeastern South Dakota) and the Ottertail River flowing from west-central Minnesota. Numerous tributaries in MLRA 56A contribute additional water to the Red River. In Minnesota these include the Two Rivers, Snake, Marsh, Middle, Red Lake, Wild Rice, and Buffalo. In North Dakota, the Pembina, Tongue, Park, Forest, Turtle, Goose, Elm, Rush, Maple, Sheyenne, and Wild Rice are tributaries to the Red River. There are also smaller streams and coulees along with many legal drains.

The relative flatness of much of the MLRA contributes to a flooding hazard for large areas of agricultural land in the spring months. Soil salinity, while variable, also impacts land management on many areas within the MLRA. Extensive surface and subsurface (tile) drainage systems have been constructed/installed to manage excess water and/or salinity on cropland. This extensive drainage has apparently reduced ground water recharge regionally, thus impacting seasonal water table level/fluctuation and its influence on plant communities. Soils that were poorly drained prior to wide-spread drainage may now function as somewhat poorly drained or even moderately well drained soils. For example, undrained Fargo soils are Wet Meadow ecological sites; with surface drainage they may function as Subirrigated sites; and with tile drainage, they commonly function as Clayey sites. Because of the extensive alteration of the hydrology, restoration to the natural conditions of the reference state dynamics would not be possible.

MLRA 56A is an ecotone between grassland dominated MLRAs 55A and 55B to the west and forest dominated MLRAs 56B and 102A to the east. This region is utilized mostly by farms; about 80 percent is non-irrigated cropland, but some irrigated fields exist on the beach areas. Cash-grain, bean, sugar beets, potatoes, and oil production crops are the principal enterprise on many farms, but other feed grains and hay are also grown.

Currently about 6 percent of this area is forested, mostly in areas along rivers that are difficult to access with farm equipment. Another 6 percent is grassland used for ranching and/or wildlife habitat. Grazing lands occur primarily in the Sand Hills area of the Sheyenne River delta, on beach areas, and on other areas too wet, saline, sodic, steep, or inaccessible to be productive cropland.

Classification relationships

Level IV Ecoregions of the Conterminous United States: 48a Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin; 48b Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas; 48c Saline Area; and 48d Lake Agassiz Plains.

Ecological site concept

The Loamy ecological site is located on flats and rises on lake plains, till-floored lake plains, delta plains, and isolated areas of till plain and on flats on glacial lake beaches. It also occurs on high terraces and side slopes above streams and rivers; these landforms are no longer impacted by frequent flooding. The soils are very deep; however, some have layers of sand and gravel in the substratum (>20 inches deep). The dark-colored surface soil is more than 7 inches thick. Surface textures typically are loam, silt loam, or silty clay loam but clay loam, very fine sandy loam, fine sandy loam, sandy loam also occur. Where fine sandy loam or sandy loam occurs, these textures are <10 inches thick. The subsoil typically is loam, clay loam, silt loam, or silty clay loam, but very fine sandy loam also occurs; the subsoil forms a ribbon 1 to 2 inches long to a depth >20 inches. Soil on this site is moderately well drained or well drained. Very slight to slight effervescence is allowed. Generally, the depth to effervescence exceeds 12 inches; however, very slight effervescence is allowable where the depth to a layer of accumulated carbonate (strong or violent effervescence) is >20 inches. Soil salinity, typically, is none to very slight in the upper 20 inches, but below that depth may increase to moderate in some soils. Slopes range from 0 to 25 percent. On the landscape, this site is below the Thin Loamy ecological site and above the Loamy Overflow, Limy Subirrigated, Wet Meadow, and Subirrigated sites. The Clayey and Sandy ecological sites occur on similar landscape positions; the subsoil of the Clayey site forms a ribbon >2 inches long while the subsoil of the Sandy site forms a ribbon <1 inch long. The transition between Loamy and Thin Loamy sites is determined by depth to accumulated carbonates. Soils with strong or violent effervescence within a depth of 8 inches are included in Thin Loamy - even where a thin, non- calcareous subsoil layer occurs above the calcic layer.

To see a full copy of the ecological site description with all tables and the full version 5 rangeland health worksheet. Please use the following hyperlink:(

https://efotg.sc.egov.usda.gov/references/public/ND/53B_Clayey_Narrative_FINAL_Ref_FSG.pdf )

Associated sites

| R056AY084ND |

Clayey This site typically occurs somewhat lower on the landscape. The subsoil layer forms a ribbon >2 inches long. |

|---|---|

| R056AY087ND |

Limy Subirrigated This site occurs lower on the landscape. It is highly calcareous in the upper part of the subsoil and has redoximorphic features at a depth of 18 to 30 inches. All textures are included in this site. |

| R056AY088ND |

Loamy Overflow This site occurs on lower, concave slopes on lake plains – a run-on position; it also occurs on floodplain steps. The surface and subsoil layers form a ribbon 1 to 2 inches long. |

| R056AY091ND |

Sandy This site occurs on lake plains. The surface and subsoil layers from a ribbon <1 inch long. |

| R056AY095ND |

Subirrigated This site occurs on concave flats and in shallow depressions which have occasional, brief ponding early in the growing season. It has redoximorphic features at a depth of 18 to 30 inches. It is >16 inches to a highly calcareous subsoil. All textures are included in this site. |

| R056AY099ND |

Thin Loamy This site occurs on higher, convex slopes on lake plains. It is effervescent within a depth of 5 inches and is highly calcareous (strong or violent effervescence) immediately below the surface layer. The surface and subsoil layers form a ribbon 1 to 2 inches long. |

| R056AY102ND |

Wet Meadow This poorly drained site occurs in depressions and flats on uplands; it also occurs on floodplains. A seasonal highwater table is typically within a depth of 1.5 feet during the months of April through June; in depressions, it is frequently ponded (typically <1.5 feet) in April and May. It typically has redoximorphic features within a depth of 18 inches. Some soils are highly calcareous. E.C. is <8 dS/m in the surface and subsoil layers. All textures are included in this site. |

Similar sites

| R056AY091ND |

Sandy This site occurs on lake plains. The surface and subsoil layers from a ribbon <1 inch long. |

|---|---|

| R056AY084ND |

Clayey This site typically occurs somewhat lower on the landscape. The subsoil layer forms a ribbon >2 inches long. |

| R056AY088ND |

Loamy Overflow This site occurs on lower, concave slopes on lake plains – a run-on position; it also occurs on floodplain steps. The surface and subsoil layers form a ribbon 1 to 2 inches long. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Andropogon gerardii |

Physiographic features

This site typically occurs on flats and rises on lake plains, delta plains, and isolated areas of till plain and on flats on glacial lake beaches. It also occurs on high terraces and side slopes above streams and rivers; these landforms are no longer impacted by frequent flooding. Parent materials include fine-silty, coarse-silty, fine- loamy, and coarse-loamy glaciolacustrine sediments and deltaic deposits; loamy or silty stream alluvium; till; and loamy (>20 inches thick) over sandy beach deposits. Slopes range from 0 to 25 percent.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Lake plain

(2) Delta plain (3) Till plain (4) Beach (5) Terrace |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Low to high |

| Flooding duration | Long (7 to 30 days) |

| Flooding frequency | None to occasional |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 750 – 1,475 ft |

| Slope | 25% |

| Ponding depth |

Not specified |

| Water table depth | 36 – 80 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

MLRA 56A is considered to have a continental climate – cold winters and relatively hot summers, low to moderate humidity, light rainfall, and much sunshine. Extremes in temperature may also abound. The climate is the result of this MLRA’s location near the geographic center of North America. There are few natural barriers on the northern Great Plains and air masses move freely across the plains and account for rapid changes in temperature.

Annual precipitation typically ranges from 18 to 23 inches per year. The average annual temperature is about 40°F. January is the coldest month with average temperatures ranging from about 1°F (Pembina, North Dakota (ND) to about 11°F (Wheaton, Minnesota (MN). July is the warmest month with temperatures averaging from about 68°F (Pembina, ND) to about 73°F (Wheaton, MN). The range of normal average monthly temperatures between the coldest and warmest months is about 65°F. This large annual range attests to the continental nature of this area's climate. Winds are estimated to average about 13 miles per hour annually, ranging from about 15 miles per hour during the spring to about 11 miles per hour during the summer. Daytime winds are generally stronger than nighttime and occasional strong storms may bring brief periods of high winds with gusts to more than 50 miles per hour.

Growth of cool season plants begins in early to mid-March, slowing or ceasing in late June. Warm season plants begin growth about mid-May and continue to early or mid-September. Greening up of cool season plants may occur in September and October when adequate soil moisture is present.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 102-126 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 132-145 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 21-24 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 87-131 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 126-150 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 20-25 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 112 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 138 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 22 in |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 3. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) VICTOR 4 NNE [USC00398652], Rosholt, SD

-

(2) PARK RIVER [USC00326857], Park River, ND

-

(3) GRAFTON [USC00323594], Grafton, ND

-

(4) WHEATON [USC00218907], Wheaton, MN

-

(5) AGASSIZ REFUGE [USC00210050], Grygla, MN

-

(6) PEMBINA [USW00014924], Pembina, ND

Influencing water features

This site does not receive significant additional water either as runoff from adjacent slopes (it is commonly in a run-off landscape position) or from stream overflow. Neither does it receive significant additional water from a seasonal high-water table. Depth to the water table typically exceeds 3 feet in the spring; however, in a few soils it may be as shallow as 2 feet early in the growing season. During the summer months, the depth is generally from 4 feet to more than 6 feet. Surface infiltration is moderately slow to moderately rapid. Permeability through the profile, typically, is moderately slow to moderate; however, in soils with contrasting substratum materials, it is very rapid where it is gravelly. Water loss is through evapotranspiration and percolation below the root zone. Where this site occurs on terraces, flooding frequency is none to occasional.

Soil features

Soils associated with Loamy ES are typically in the Mollisol order. The Mollisols are classified further as Aquic Argiudolls, Calcic Argiudolls, Oxyaquic Argiudolls, Calcic Hapludolls, Cumulic Hapludolls (>6% slope on uplands or on terraces), Oxyaquic Hapludolls, Pachic Hapludolls, or Typic Hapludolls. These soils were developed under prairie vegetation. The soils in this site commonly formed in glaciolacustrine sediments, deltaic deposits, beach deposits, till, or alluvium.

The common feature of soils in this site are the medium and moderately fine textures through most of the root zone; the soil forms a ribbon 1 to 2 inches long between depths of 10 and 20 inches. Surface textures typically are loam, silt loam, or silty clay loam but clay loam, very fine sandy loam, fine sandy loam, sandy loam also occur. Where fine sandy loam or sandy loam occurs, these textures are <10 inches thick. The subsoil typically is loam, clay loam, silt loam, or silty clay loam, but very fine sandy loam also occurs; the subsoil forms a ribbon 1 to 2 inches long to a depth >20 inches. Some soils have clayey substrata and others have sand and/or gravel substrata; a few soils in the northwest part of the MLRA have substrata material which is very high in shale content. Where these contrasting materials occur, they are at a depth >20 inches. Soils in this site are well drained or moderately well drained; where present, redoximorphic features are deeper than 30 inches.

Soil salinity is none to very slight (E.C. <4 dS/m). Typically, sodicity is none to low (SAR <2) to a depth >30 inches. Soil reaction is slightly acid to slightly alkaline (pH 6.1 to 7.8) in the surface layer and upper part of the subsoil. It commonly increases to moderately alkaline (pH 7.9 to 8.4) in the lower subsoil due to a layer of calcium carbonate accumulation. Where present, this layer is typically below a depth of 10 inches and the layers above do not effervesce. In the layer of accumulation, CaCO3 can be as much as 30 percent.

The soil surface is stable and intact. These soils are mainly susceptible to water erosion. The hazard of water erosion increases where vegetative cover is not adequate. Loss of the soil surface layer can result in a shift in species composition and/or production.

Major soil series correlated to the Loamy site are Aastad, Aazdahl, Barnes, Beotia, Croke, Darnen, Eckman, Fairdale, Fordville, Forman, Gardena, Great Bend, Heimdal, Lankin, La Prairie, LaDelle, Overly, Svea, Vang, and Walsh.

Access Web Soil Survey ( https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/WebSoilSurvey.aspx ) for specific local soils information.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Glaciolacustrine deposits

(2) Alluvium (3) Till (4) Lacustrine deposits |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Very cobbly, very stony loam (2) Very cobbly, very stony silt loam (3) Very cobbly, very stony silty clay loam (4) Very cobbly, very stony clay loam (5) Very cobbly, very stony very fine sandy loam (6) Loam (7) Silt loam (8) Silty clay loam (9) Clay loam (10) Very fine sandy loam |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderate |

| Depth to restrictive layer | 20 – 80 in |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 15% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 20% |

| Available water capacity (0-60in) |

5 – 12 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

30% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-20in) |

4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-20in) |

2 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-20in) |

6.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-40in) |

15% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-40in) |

5% |

Ecological dynamics

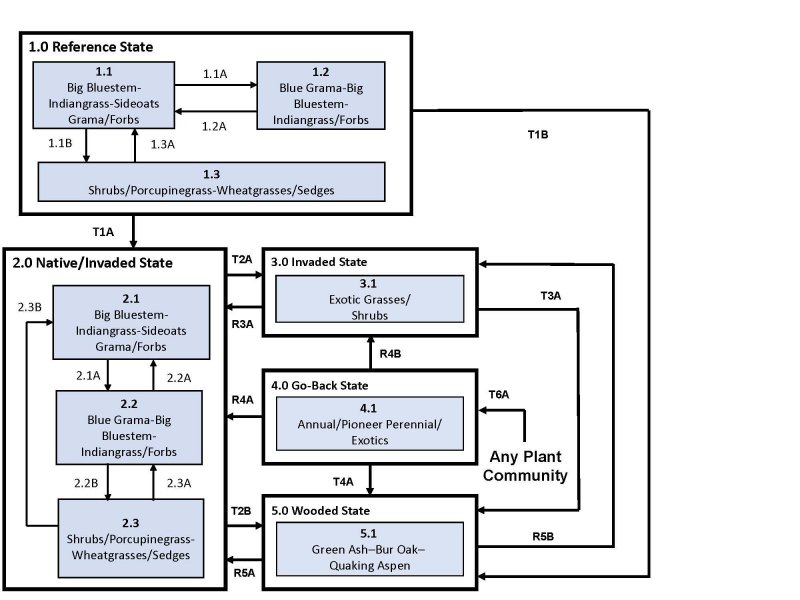

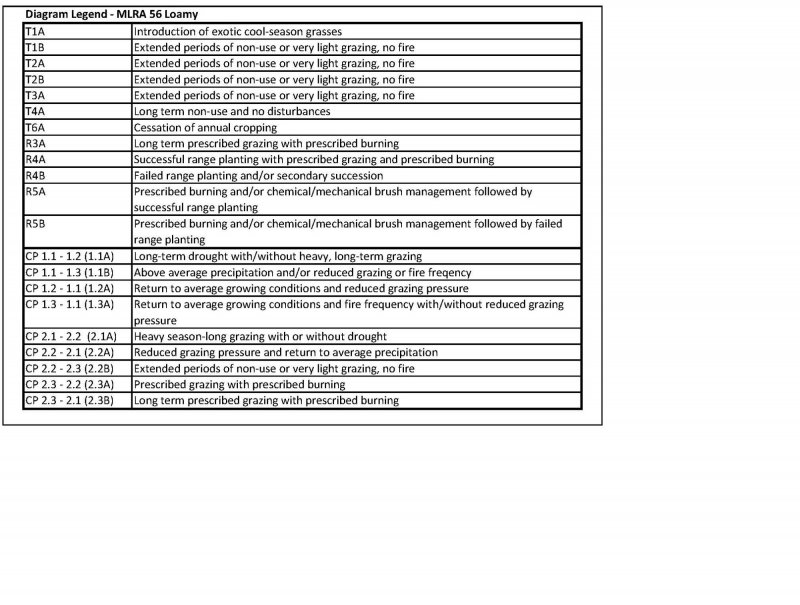

This ecological site description is based on nonequilibrium ecology and resilience theory and utilizes a State- and-Transition Model (STM) diagram to organize and communicate information about ecosystem change as a basis for management. The ecological dynamics characterized by the STM diagram reflect how changes in ecological drivers, feedback mechanisms, and controlling variables can maintain or induce changes in plant community composition (phases and/or states). The application of various management actions, combined with weather variables, impact the ecological processes which influence the competitive interactions, thereby maintaining or alter plant community structure.

Prior to European influence, the historical disturbance regime for MLRA 56A included frequent fires, both anthropogenic and natural in origin. Most fires, however, were anthropogenic fires set by Native Americans. Native Americans set fires in all months except perhaps January. These fires occurred in two peak periods, one from March-May with the peak in April and another from July-November with the peak occurring in October. Most of these fires were scattered and of small extent and duration. The grazing history would have involved grazing and browsing by large herbivores (such as American bison, elk, and whitetail deer). Herbivory by small mammals, insects, nematodes, and other invertebrates are also important factors influencing the production and composition of the communities. Grazing and fire interaction, particularly when coupled with drought events, influenced the dynamics discussed and displayed in the following state and transition diagram and descriptions.

Following European influence, this ecological site generally has had a history of grazing by domestic livestock, particularly cattle, which along with other related activities (e.g., fencing, water development, fire suppression) has changed the disturbance regime of the site. Changes will occur in the plant communities due to these and other factors.

Weather fluctuations, coupled with managerial factors, may lead to changes in the plant communities and, under adverse impacts, may result in a slow decline in vegetative vigor and composition. However, under favorable conditions the botanical composition may resemble that prior to European influence.

Five vegetative states have been identified for the site (Reference, Native/Invaded, Invaded, Go-Back, and Wooded). Within each state, one or more community phases have been identified. These community phases are named based on the more dominant and visually conspicuous species; they have been determined by study of historical documents, relict areas, scientific studies, and ecological aspects of plant species and plant communities. Transitional pathways and thresholds have been determined through similar methods.

State 1: Reference State represents the natural range of variability that dominated the dynamics of this ecological site prior to European influence. Dynamics of the state were largely determined by variations in climate and weather (e.g., drought), as well as that of fire (e.g., timing, frequency) and grazing by native herbivores (e.g., frequency, intensity, selectivity). Due to those variations, the Reference State is thought to have shifted temporally and spatially between three plant community phases.

Presently, the primary disturbances include widespread introduction of exotic plants, concentrated livestock grazing, lack of fire, and perhaps long-term non-use or very light grazing and no fire. Because of these changes, particularly the widespread occurrence of exotic species, as well as other environmental changes, the Reference State is considered to no longer exist. Thus, the presence of exotic plants on the site precludes it from being placed in the Reference State. It must then be placed in one of the other states, commonly State 2: Native/Invaded State. This state may transition to State 2: Native/Invaded State with the colonization of exotic cool-season grasses (T1A). It may also transition to State 5: Invaded Wooded State during long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire (T1B).

State 2: Native/Invaded State. Colonization of the site by exotic plants will cause a transition from State 1: Reference State to State 2: Native/Invaded State (T1A). This transition was inevitable; it often resulted from colonization by exotic cool-season grasses (such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass) which have been particularly and consistently invasive under long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire. Other exotic plants (e.g., Canada thistle, leafy spurge) are also known to invade the site.

Three community phases have been identified for this state; they are similar to the community phases in the Reference State but have now been invaded by exotic cool-season grasses. These exotic cool-season grasses can be expected to increase. As that increase occurs, a decline in forb diversity can be expected. Under non-use or minimal use management, mulch increases and may become a physical barrier to plant growth. This also changes the micro-climate near the soil surface and may alter infiltration, nutrient cycling, and biological activity near the soil surface. As a result, these factors, coupled with shading, cause desirable native plants to have increasing difficulty remaining viable and recruitment declines.

To slow or limit the invasion of these exotic grasses or other exotic plants, it is imperative that managerial techniques (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed burning) be carefully constructed, monitored, and evaluated with respect to that objective. If management does not include measures to control or reduce these exotic plants, the transition to State 3: Invaded State should be expected (T2A). This state may also transition to State 5: Invaded Wooded State during long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire (T2B).

State 3: Invaded State. The threshold for this state is reached when both the exotic cool-season grasses (e.g., Kentucky bluegrass, quackgrass, smooth brome) exceed 30% of the plant community and native grasses represent less than 40% of the community. One plant community phase has been identified for this state.

The exotic cool-season grasses can be quite invasive and often form monotypic stands. As they increase, both forage quantity and quality of the annual production becomes increasingly restricted to late spring and early summer, even though annual production may increase. Forb diversity often declines. Under non-use or minimal use management, mulch increases and may become a physical barrier to plant growth. This may also alter infiltration, nutrient cycling, and biological activity near the soil surface. As such, desirable native plants become increasingly displaced.

Once the state is well established, prescribed burning and prescribed grazing techniques have been largely ineffective in suppressing or eliminating the exotic cool-season grasses, even though some short-term reductions may appear successful. However, assuming there is an adequate component of native grasses to respond to treatments, a restoration pathway to State 2: Native/Invaded State (R3A) may be accomplished with the implementation of long-term prescribed grazing in conjunction with prescribed burning. This state may also transition to State 5: Invaded Wooded State during long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire (T3A).

State 4: Go-Back State often results following cropland abandonment and consists of only one plant community phase. This weedy assemblage may include noxious weeds that need control. Over time, the exotic cool-season grasses (e.g., Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, quackgrass) will likely predominate. Initially, due to extensive bare ground and a preponderance of shallow rooted annual plants, infiltration is low and the potential for soil erosion is high. Plant species richness may be high, but overall diversity (i.e., equitability) is typically low with the site dominated by a relatively small assemblage of species. Due to the lack of native perennials and other factors, restoring the site with the associated ecological processes is difficult. However, a successful range planting may result in something approaching State 2: Native/Invaded State (R4A). Following planting, prescribed grazing, prescribed burning, haying, and the use of herbicides will generally be necessary to achieve the desired result and control weeds, some of which may be noxious weeds. A failed range planting and/or secondary succession will lead to State 3: Invaded State (R4B). This state may also transition to State 5: Invaded Wooded State during long-term non-use and no fire (T4A).

State 5: Invaded Wooded State. This state historically existed as small patches of trees and/or shrubs scattered across the site when precipitation, fire frequency, and other factors enabled woody species to colonize or encroach on the site. This often resulted in a mosaic of patches of woody vegetation interspersed within the grass-dominated vegetation. Marked increases in non-use management and active fire suppression since European influence have enabled this state to expand and become more widespread. One community phase has been identified and often results from long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire (T2B, T3A, T4A).

Prescribed burning and/or chemical/mechanical brush management followed by a successful range planting may lead to State 2: Native/Invaded State (R5A). Failure of the range planting followed by secondary succession, however, will lead to State 3: Invaded State (R5B).

The following state and transition model diagram illustrates the common states, community phases, community pathways, and transition and restoration pathways that can occur on the site. These are the most common plant community phases and states based on current knowledge and experience; changes may be made as more data are collected. Pathway narratives describing the site’s ecological dynamics reference various management practices (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed burning, brush management, herbaceous weed treatment) which, if properly designed and implemented, will positively influence plant community competitive interactions. The design of these management practices will be site specific and should be developed by knowledgeable individuals; based upon management goals and a resource inventory; and supported by an ongoing monitoring protocol.

When the management goal is to maintain an existing plant community phase or restore to another phase within the same state, modification of existing management to ensure native species have the competitive advantage may be required. To restore a previous state, the application of two or more management practices in an ongoing manner will be required. Whether using prescribed grazing, prescribed burning, or a combination of both with or without additional practices (e.g., brush management), the timing and method of application needs to favor the native species over the exotic species. Adjustments to account for variations in annual growing conditions and implementing an ongoing monitoring protocol to track changes and adjust management inputs to ensure desired outcome will be necessary.

The plant community phase composition table(s) has been developed from the best available knowledge including research, historical records, clipping studies, and inventory records. As more data are collected, plant community species composition and production information may be revised.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

States 2 and 5 (additional transitions)

| T1A | - | Introduction of exotic cool-season grasses |

|---|---|---|

| T2A | - | Long-term non-use or very light grazing, no fire |

| T2B | - | Long-term non-use or very light grazing, no fire |

| R3A | - | Long-term prescribed grazing and prescribed burning |

| T3A | - | Long-term non-use or very light grazing, no fire |

| R4A | - | Successful range planting |

| R4B | - | Failed range planting and/or secondary succession |

| T4A | - | Long term non-use or very light grazing, no fire |

| R5A | - | Prescribed burning and/or chemical/mechanical brush management followed by successful range planting |

| R5B | - | Prescribed burning and/or chemical/mechanical brush management followed by failed range planting |

| T6A | - | Cessation of annual cropping |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

| 1.1A | - | Multiyear drought with/without heavy, long-term grazing |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1B | - | Above average precipitation and/or reduced grazing or fire frequency |

| 1.2A | - | Return to average precipitation and reduced grazing |

| 1.3A | - | Return to average precipitation and fire frequency with/without reduced grazing |

State 2 submodel, plant communities

| 2.1A | - | Heavy grazing with or without drought |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2A | - | Long-term prescribed burning and prescribed grazing, return to average precipitation |

| 2.2B | - | Long-term non-use or very light grazing, no fire |

| 2.3A | - | Long-term prescribed grazing and prescribed burning |

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

This state represents the natural range of variability that dominated the dynamics of this ecological site prior to European influence. The primary disturbance mechanisms for this site in the reference condition included frequent fire and grazing by large herding ungulates. Timing of fires and grazing, coupled with weather events, dictated the dynamics that occurred within the natural range of variability. These factors likely caused the community to shift both spatially and temporally between three community phases.

Characteristics and indicators. (i.e., characteristics and indicators that can be used to distinguish this state from others). Because of changes in disturbances and other environmental factors (particularly the widespread occurrence of exotic species), the Reference State is considered to no longer exist.

Resilience management. (i.e., management strategies that will sustain a state and prevent a transition). If intact, the reference state should probably be managed with current disturbance regimes which have permitted the site to remain in reference condition, as well as maintaining the quality and integrity of associated ecological sites. Maintenance of the reference condition is contingent upon a monitoring protocol to guide management.

Community 1.1

Big Bluestem-Indiangrass-Sideoats Grama/ Forbs (Andropogon gerardii-Sorghastrum nutans-Bouteloua curtipendula/ Forbs)

This Community Phase was historically the most dominant both temporally and spatially, with warm-season grasses dominating the community. The major grasses and sedges included big bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass, sideoats grama, little bluestem, prairie dropseed, porcupinegrass, and green needlegrass. Other associated grasses included needle and thread, western wheatgrass, slender wheatgrass, bearded wheatgrass, blue grama, and upland sedges. Blazing star, common yarrow, purple prairie clover, blacksamson echinacea, silverleaf Indian breadroot, upright prairie coneflower, stiff sunflower, and stiff goldenrod were among the more common forbs. Common shrubs likely included leadplant, prairie rose, western snowberry, and prairie sagewort. Annual production likely varied between about 1900-3900 pounds per acre with grasses and grass-likes, forbs, and shrubs contributing about 85%, 10%, and 5% respectively. This community represents the plant community phase upon which interpretations are primarily based and is described in the “Plant Community Composition and Group Annual Production” portion of this ecological site description.

Figure 7. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1615 | 2465 | 3315 |

| Forb | 190 | 290 | 390 |

| Shrub/Vine | 95 | 145 | 195 |

| Total | 1900 | 2900 | 3900 |

Community 1.2

Blue Grama-Big Bluestem-Indiangrass/ Forbs (Bouteloua gracilis- Andropogon gerardii-Sorghastrum nutans/ Forbs)

This Community Phase occurred with long-term drought with or without heavy long-term grazing. This resulted in an increase in blue grama with a corresponding decrease in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama. The forb and shrub component of this community was similar to that of Community Phase 1.1 but some species (e.g. prairie sagewort) may have markedly increased.

Community 1.3

Shrubs/ Porcupinegrass-Wheatgrasses/ Sedges (Shrubs/ Hesperostipa spartea-Elymus caninus, Elymus trachycaulus/ Carex spp.)

This Community Phase occurred during periods of above average precipitation and/or reduced grazing or fire frequency. It may be characterized as a shrub dominated community consisting of a mixture of species such as western snowberry, prairie rose, leadplant, American plum, or chokecherry. Associated grasses often included porcupinegrass, bearded wheatgrass, and slender wheatgrass, along with upland sedges. Canada goldenrod, white heath aster, wavyleaf thistle, and common yarrow were likely among the common forbs.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Community Phase Pathway 1.1 to 1.2 occurred during multiyear drought with or without heavy-long term grazing or other conditions that resulted in an increase in blue grama with corresponding decreases in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Community Phase Pathway 1.1 to 1.3 occurred with above average precipitation and/or reduced grazing or fire frequency resulting in marked increases in shrubs (e.g., western snowberry), porcupinegrass, wheatgrass, and sedges with corresponding decreases in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Community Phase Pathway 1.2 to 1.1 occurred with the return to average precipitation and reduced grazing which led to a decrease in blue grama with corresponding increases in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.1

Community Phase Pathway 1.3 to 1.1 occurred upon return to average precipitation and fire frequency with/without reduced grazing. This would have resulted in decreases in shrubs, porcupinegrass, wheatgrasses, and sedges with corresponding increases in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama.

State 2

Native/Invaded State

This state is similar to State 1: Reference State but has now been colonized by the exotic cool-season grasses (e.g., Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, quackgrass) which are now present in small amounts. Although the state is still dominated by native grasses, an increase in these exotic cool-season grasses can be expected. These exotic cool-season grasses can be quite invasive on the site and are particularly well adapted to heavy grazing. They also often form monotypic stands. As these exotic cool-season grasses increase, both forage quantity and quality become increasingly restricted to late spring and early summer due to the monotypic nature of the stand, even though annual production may increase. Native forbs generally decrease in production, abundance, diversity, and richness compared to that of State 1: Reference State. These exotic cool-season grasses have been particularly and consistently invasive under extended periods of non-use and no fire. To slow or limit the invasion of these exotic grasses, it is imperative that managerial techniques (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed burning) be carefully constructed, monitored, and evaluated with respect to that objective. If management does not include measures to control or reduce these exotic cool-season grasses, the transition to State 3: Invaded State should be expected. Annual production of this state can be quite variable, in large part due to the amount of exotic cool-season grasses. Annual production may range from 1800-3800 pounds per acre.

Characteristics and indicators. (i.e., characteristics that can be used to distinguish this state from others). The presence of trace amounts of exotic cool-season grasses indicates a transition from State 1 to State 2. The presence of exotic biennial or perennial leguminous forbs (i.e., sweet clover, black medic) may not, on their own, indicate a transition from State 1 to State 2 but may facilitate that transition.

Resilience management. (i.e., management strategies that will sustain a state and prevent a transition). To slow or limit the invasion of these exotic grasses, it is imperative that managerial techniques (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed burning) be carefully constructed, monitored, and evaluated with respect to that objective. Grazing management should be applied that enhances the competitive advantage of native grass and forb species. This may include: (1) grazing when exotic cool-season grasses are actively growing and native cool- season grasses are dormant; (2) applying proper deferment periods allowing native grasses to recover and maintain or improve vigor; (3) adjusting overall grazing intensity to reduce excessive plant litter (above that needed for rangeland health indicator #14 – see Rangeland Health Reference Worksheet); (4) incorporating early heavy spring utilization which focuses grazing pressure on exotic cool-season grasses and reduces plant litter, provided that livestock are moved when grazing selection shifts from exotic cool-season grasses to native grasses. Prescribed burning should be applied in a manner that maintains or enhances the competitive advantage of native grass and forb species. Prescribed burns should be applied as needed to adequately reduce/remove excessive plant litter and maintain the competitive advantage for native species. Timing of prescribed burns (spring vs. summer vs. fall) should be adjusted to account for differences in annual growing conditions and applied during windows of opportunity to best shift the competitive advantage to the native species.

Community 2.1

Big Bluestem-Indiangrass-Sideoats Grama/Forbs (Andropogon gerardii-Sorghastrum nutans-Bouteloua curtipendula/Forbs)

Figure 8. Community Phase 2.1: Big Bluestem-Indiangrass-Sideoats Grama/Forbs.

This community phase is very similar to Community Phase 1.1, but now has been colonized by exotic cool- season grasses (e.g., Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, quackgrass).

Community 2.2

Blue Grama-Big Bluestem-Indiangrass/Forbs (Bouteloua gracilis- Andropogon gerardii-Sorghastrum nutans/Forbs)

This Community Phase is similar to Community Phase 1.2 but has now been colonized by exotic cool-season grasses, often Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass. These exotics, however, are present in smaller amounts with the community still dominated by native grasses. This community phase is often dispersed throughout a pasture in an overgrazed/undergrazed pattern, typically referred to as patch grazing. Some overgrazed areas will exhibit the impacts of heavy use, while the ungrazed areas will have a build-up of litter and increased plant decadence. This is a typical pattern found in properly stocked pastures grazed season long. As a result, Kentucky bluegrass tends to increase more in the undergrazed areas while the more grazing tolerant short statured species such as blue grama and sedges increase in the heavily grazed areas. If present, Kentucky bluegrass may increase under heavy grazing. This Community Phase is approaching the threshold leading to a transition to State 3: Invaded State. As a result, it is an “at risk” community. If management does not include measures to control or reduce these exotic cool-season grasses, the transition to State 3: Invaded State should be expected.

Community 2.3

Shrubs/Porcupinegrass-Wheatgrasses/Sedges (Shrubs/Hesperostipa spartea-Elymus caninus, Elymus trachycaulus/Carex spp.)

This community phase is similar to Community Phase 1.3 but has now been colonized by exotic cool-season grasses (e.g., Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, quackgrass). These exotic grasses, however, are present in smaller amounts with the community still dominated by native grasses.

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Community Pathway 2.1 to 2.2 occurs with heavy grazing with or without drought. Blue grama increases with corresponding decreases in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Community Phase Pathway 2.2 to 2.1 occurs with the implementation of long-term prescribed grazing and prescribed burning, and a return to average precipitation. This results in increases in big bluestem, Indiangrass, and sideoats grama with a corresponding decrease in blue grama.

Pathway 2.2B

Community 2.2 to 2.3

Community Phase Pathway 2.2 to 2.3 occurs during long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire, resulting in an increase in mulch accumulation along with marked increases in shrubs, forbs, and exotic cool- season grasses.

Pathway 2.3A

Community 2.3 to 2.1

Community Phase Pathway 2.3 to 2.2 occurs with the implementation of long-term prescribed grazing and prescribed burning. Prescribed grazing incorporates heavy early spring and/or late fall grazing of cool-season exotic grasses when cool-season exotic grass is most vulnerable, shifting the competitive advantage to the remaining native species. Prescribed burning will likely require repeated treatments to complete the pathway to target exotic cool-season grass invasion and because many of the shrubs (e.g., western snowberry) sprout profusely following one burn.

State 3

Invaded State

This state is the result of invasion and dominance by the exotic cool-season grasses (commonly Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass). These exotic cool-season grasses can be quite invasive on the site and are particularly well adapted to heavy grazing. They also often form monotypic stands. As these exotic cool-season grasses increase, both forage quantity and quality become increasingly restricted to late spring and early summer due to the monotypic nature of the stand, even though annual production may increase. Native forbs generally decrease in production, abundance, diversity, and richness compared to that of State 1: Reference State. Common forbs often include white heath aster, goldenrod, common yarrow, and white sagebrush. Shrubs, such as western snowberry and prairie rose, may increase. Once the state is well established, prescribed burning and grazing techniques have been largely ineffective in suppressing or eliminating these species, even though some short-term reductions may appear successful. Annual production of this state may vary widely, in part due to variations in the extent of invasion by exotic cool-season grasses. However, annual production may be in the range of 1300-3700 pounds per acre.

Characteristics and indicators. (i.e., characteristics that can be used to distinguish this state from others). This site is characterized by exotic cool-season grasses constituting greater than 30 percent of the annual production and native grasses constituting less than 40 percent of the annual production.

Resilience management. (i.e., management strategies that will sustain a state and prevent a transition). Light or moderately stocked continuous, season-long grazing or a prescribed grazing system which incorporates adequate deferment periods between grazing events and proper stocking rate levels will maintain this State. Application of herbaceous weed treatment, occasional prescribed burning and/or brush management may be needed to manage noxious weeds and increasing shrub (e.g., western snowberry) populations.

Community 3.1

Exotic Grasses/Shrubs

This Community Phase is dominated by exotic, cool-season sodgrasses (such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass), often with a reduced forb component. Excessive accumulation of mulch may also be present, particularly when dominated by Kentucky bluegrass. Common forbs and shrubs often include white heath aster, goldenrod, common yarrow, and white sagebrush. Shrubs, such as western snowberry and prairie rose, may increase. Total production may be in the range of 3,000 pounds per acre with over 60% of total production attributable to the exotic cool-season grasses. The longer this community phase exists, the more resilient it becomes. Natural or management disturbances that reduce the cover of Kentucky bluegrass or smooth brome are typically short-lived.

State 4

Go-Back State

This state is highly variable depending on the level and duration of disturbance related to the T6A transitional pathway. In this MLRA, the most probable origin of this state is plant succession following cropland abandonment. This plant community will initially include a variety of annual forbs and grasses, some of which may be noxious weeds needing control. Over time, the exotic cool-season grasses (Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass) will likely predominate.

Characteristics and indicators. (i.e., characteristics that can be used to distinguish this state from others). Tillage has destroyed the native plant community, altered soil structure and biology, reduced soil organic matter, and resulted in the formation of a tillage induced compacted layer which is restrictive to root growth. Removal of perennial grasses and forbs results in decreased infiltration and increased runoff.

Resilience management. (i.e., management strategies that will sustain a state and prevent a transition). Continued tillage will maintain the state. Control of noxious weeds will be required.

Community 4.1

Annual/Pioneer Perennial /Exotics

This Community Phase is highly variable depending on the level and duration of disturbance related to the T6A transitional pathway. In this MLRA, the most probable origin of this phase is secondary succession following cropland abandonment. This plant community will initially include a variety of annual forbs and grasses, including noxious weeds (e.g., Canada thistle) which may need control. Over time, the exotic cool-season grasses (Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass) will likely predominate.

State 5

Invaded Wooded State

This state historically existed as small patches of trees and/or shrubs scattered across the site, where trees and shrubs could have encroached onto the site vegetatively (e.g., rhizomes, root sprouts) or provided a seed source for colonization of the site. Variations in fire frequency enabled woody plant species in some areas (i.e., period of infrequent fire) to grow large enough to escape the next fire event. As trees increased in size, canopy cover increased which altered micro-climate and reduced fine fuel amounts resulting in reduced fire intensity and frequency. This would have been the primary pathway under the historic disturbance regime and would have resulted in a mosaic pattern of small, wooded patches interspersed within herbaceous plant community phases. A marked increase in non-use management and active fire suppression since European influence has enabled this state to expand and become more widespread. Common woody species often include bur oak, green ash, and small patches of quaking aspen clones with an understory of smaller trees and shrubs (often including western snowberry, prairie rose, and chokecherry). Buckthorn is increasing in MLRA 56A and can become invasive in this plant community. An herbaceous component of smooth brome, wildrye, and/or Kentucky bluegrass is often present, particularly when the canopy is more open. Under more closed canopies, the herbaceous understory is predominantly shade- tolerant sedges (e.g., Sprengel’s sedge).

Characteristics and indicators. (i.e., characteristics and indicators that can be used to distinguish this state from others). The dominance of woody species (by cover and production) distinguishes this state from other herbaceously dominated states.

Resilience management. (i.e., management strategies that will sustain a state and prevent a transition). This state is resistant to change in the long-term absence of fire. Restoration efforts would require the use of prescribed fire, mechanical treatment, and prescribed grazing. Considerable time and effort will be required to restore to other states.

Community 5.1

Green Ash-Bur Oak-Quaking Aspen (Fraxinus pennsylvanica-Quercus macrocarpa-Populus tremuloides)

This plant community phase is often characterized by a dominance of green ash, bur oak, and quaking aspen with lesser amounts of American plum, boxelder, and perhaps ironwood. Shrubs include chokecherry, prairie rose, and western snowberry. An herbaceous understory of sedges, wildrye, and assorted forbs may also be present. Regardless of how this community phase originated, the exotic cool-season grasses (Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass) will generally be prominent components. As the trees mature and canopy cover increases, herbaceous production declines and shrubs/vines associated with mature woodlands may begin to occupy the understory.

State 6

Any Plant Community

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

This is the transition from the State 1: Reference State to the State 2: Native/Invaded State due to the introduction and establishment of exotic cool-season grasses (typically Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and/or quackgrass). This transition was inevitable and corresponded to a decline in native warm-season and cool-season grasses; it may have been exacerbated by chronic season-long or heavy late season grazing. Complete rest from grazing and suppression of fire could also have hastened the transition. The threshold between states was crossed when Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, quackgrass, or other exotic plants became established on the site.

Constraints to recovery. (i.e., variables or processes that preclude recovery of the former state). Current knowledge and technology will not facilitate a successful restoration to Reference State.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

This transition from State 2: Native/Invaded State to State 3: Invaded State generally occurs with long-term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire. Exotic cool-season grasses (e.g., quackgrass, Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome) become the dominant graminoids. Studies indicate that a threshold may exist in this transition when both the exotic cool-season grasses exceed 30% of the plant community and native grasses represent less than 40% of the plant community composition. This transition may occur under other management including heavy season-long grazing (primarily Kentucky bluegrass).

Constraints to recovery. (i.e., variables or processes that preclude recovery of the former state). Variations in growing conditions (e.g., cool, wet spring) will influence the effects of various management activities on exotic cool-season grass populations.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 5

This transition from the State 2: Native/Invaded to State 5: Invaded Wooded State generally occurs with long- term non-use or very light grazing, and no fire. It frequently occurs when the site is in close proximity to wooded areas where the woodland vegetation may encroach vegetatively and/or serve as a seed source for these species to colonize the site. The Invaded Wooded State has become more frequent following European settlement since the historic fire regime has been markedly reduced.

Constraints to recovery. (i.e., variables or processes that preclude recovery of the former state). The extended fire interval may make recovery doubtful due to the abundance of exotic cool-season grasses and lack of native grasses. Fire intensity along with consumption of available fuels may cause incomplete or patchy burns. Continued recruitment of tree seeds from adjacent sites will hamper site restoration. Constraints to recovery include reticence to undertake tree removal and the perception that trees may be a desirable vegetation component for wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, aesthetics, etc. are some of the constraints to recovery. Managers wanting to manage the site for deer, livestock, or grassland nesting birds will need to consider the intensive management required to restore and maintain the site in State 2. The disturbance regime necessary to restore this site to State 2: Native/Invaded State is very labor intensive and costly; therefore, addressing woody removal earlier in the encroachment phase is the most cost-effective treatment for woody control.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

This restoration pathway from the State 3: Invaded State 2: Native/Invaded State may be initiated with the implementation of long-term prescribed burning with prescribed grazing, assuming there is an adequate component of native grasses to respond to the treatments. Both prescribed grazing and prescribed burning are likely necessary to successfully initiate this restoration pathway, the success of which depends upon the presence of a remnant population of native grasses in Community Phase 3.1. That remnant population, however, may not be readily apparent without close inspection. The application of several prescribed burns may be needed at relatively short intervals in the early phases of this restoration process, in part because many of the shrubs (e.g., western snowberry) sprout profusely following one burn. Early season prescribed burns have been successful; however, fall burning may also be an effective technique. Common forb and shrub associates include northern bedstraw, common dandelion, Canada goldenrod, common yarrow, Canada thistle, western snowberry, and prairie rose. If the site is adjacent to woodlands, sprouts and seeds from the woodland species may begin to encroach and colonize the site.

Context dependence. (i.e., factors that cause variations in plant community shifts, restoration likelihood, and contribute to uncertainty). Grazing management should be applied in a manner that enhances/maximizes the competitive advantage of native grass and forb species over the exotic species. This may include the use of prescribed grazing to reduce excessive plant litter accumulations above that needed for rangeland health indicator #14 (see Rangeland Health Reference Worksheet). Increasing livestock densities may facilitate the reduction in plant litter provided length and timing of grazing periods are adjusted to favor native species. Grazing prescriptions designed to address exotic grass invasion and favor native species may involve earlier, short, intense grazing periods with proper deferment to improve native species health and vigor. Fall (e.g., September, October) prescribed burning followed by an intensive, early spring graze period with adequate deferment for native grass recovery may shift the competitive advantage to the native species, facilitating the restoration to State 2: Native/Invaded. Prescribed burning should be applied in a manner that enhances the competitive advantage of native grass and forb species over the exotic species. Prescribed burns should be applied at a frequency which mimics the natural disturbance regime, or more frequently as is ecologically (e.g., available fuel load) and economically feasible. Burn prescriptions may need adjustment to: (1) account for change in fine fuel orientation (e.g., “flopped” Kentucky bluegrass); (2) fire intensity and duration by adjusting ignition pattern (e.g., backing fires vs head fires); (3) account for plant phenological stages to maximize stress on exotic species while favoring native species (both cool- and warm-season grasses).

Transition T3A

State 3 to 5

This transition pathway from State 3: Invaded State to State 5: Invaded Wooded State may be initiated by extended periods of non-use or very light grazing, and no fire. This frequently occurs when the site is in close proximity to wooded areas where the woodland vegetation may encroach vegetatively and/or serve as a seed source for these species to colonize the site. It has also become more frequent following European settlement since the historic fire regime has been markedly reduced.

Constraints to recovery. (i.e., variables or processes that preclude recovery of the former state). The extended fire interval may make recovery doubtful due to the abundance of exotic cool-season grasses and lack of native grasses. Fire intensity along with consumption of available fuels may cause incomplete or patchy burns. Continued recruitment of tree seeds from adjacent sites will hamper site restoration. Constraints to recovery include the reticence to undertake tree removal and the perception that trees may be a desirable vegetation component for wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, aesthetics, etc. Managers wanting to manage the site for deer, livestock, or grassland nesting birds will need to consider the intensive management required to restore and maintain the site in State 2. The disturbance regime necessary to restore this site to State 2: Native/Invaded State is very labor intensive and costly; therefore, addressing woody removal earlier in the encroachment phase is the most cost-effective treatment for woody control.

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 2

The restoration pathway from State 4: Go-Back State to State 2: Native/Invaded State may result from a successful range planting with prescribed grazing and prescribed burning. Following planting, prescribed grazing, prescribed burning, haying, or use of herbicides will generally be necessary to achieve the desired result and control any noxious weeds. It may be possible using selected plant materials and agronomic practices to approach something very near the functioning of State 2: Native/Invaded State. Application of chemical herbicides and the use of mechanical seeding methods using adapted varieties of the dominant native grasses are possible and can be successful. After establishment of the native plant species, prescribed grazing should include adequate recovery periods following each grazing event and stocking levels which match the available resources; management objectives must include the maintenance of those species, the associated reference state functions, and continued treatment of exotic grasses.

Context dependence. (i.e., factors that cause variations in plant community shifts, restoration likelihood, and contribute to uncertainty). A successful range planting will include proper seedbed preparation, weed control (both prior to and after the planting), selection of adapted native species representing functional/structural groups inherent to the State 1, and proper seeding technique. Management (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed burning) during and after establishment must be applied in a manner that maintains the competitive advantage for the seeded native species. Adding non-native species can impact the above and below ground biota. Elevated soil nitrogen levels have been shown to benefit smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass more than some native grasses. As a result, fertilization, exotic legumes in the seeding mix, and other techniques that increase soil nitrogen may promote smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass invasion. The method or methods of herbaceous weed treatment will be site specific to each situation; but generally, the goal would be to apply the pesticide, mechanical control, or biological control (either singularly or in combination) in a manner that shifts the competitive advantage from the targeted species to the native grasses and forbs. The control method(s) should be as specific to the targeted species as possible to minimize impacts to non-target species.

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 3

A failed range planting and/or secondary succession will lead to State 3: Invaded State.

Context dependence. (i.e., factors that cause variations in plant community shifts, restoration likelihood, and contribute to uncertainty). Failed range plantings can result from many causes (both singularly and in combination) including drought, poor seedbed preparation, improper seeding methods, seeded species not adapted to the site, insufficient weed control, herbicide carryover, poor seed quality (purity & germination), and/or improper management.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 5

The transition from State 4: Go-Back State to State 5: Invaded Wooded State may occur with long-term non- use and no disturbances. This frequently occurs when the site is in close proximity to wooded areas where the woodland vegetation may encroach vegetatively and/or serve as a seed source for these species to colonize the site. It has also become more frequent following European settlement since the historic fire regime has been markedly reduced.

Constraints to recovery. (i.e., variables or processes that preclude recovery of the former state). The extended fire interval may make recovery doubtful due to the abundance of exotic cool-season grasses and lack of native grasses. Fire intensity along with consumption of available fuels may cause incomplete or patchy burns. Continued recruitment of tree seeds from adjacent sites will hamper site restoration. Constraints to recovery include reticence to undertake tree removal and the perception that trees may be a desirable vegetation component for wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, aesthetics, etc. Managers wanting to manage the site for deer, livestock, or grassland nesting birds will need to consider the intensive management required to restore and maintain the site in State 2. The disturbance regime necessary to restore this site to State 2: Native/Invaded State is very labor intensive and costly; therefore, addressing woody removal earlier in the encroachment phase is the most cost-effective treatment for woody control.

Restoration pathway R5A

State 5 to 2

Restoration Pathway from State 5: Invaded Wooded State to State 2: Native/Invaded State occurs with the implementation of prescribed burning and/or chemical/mechanical brush management followed by successful range planting. A combination of mechanical brush management, chemical treatment, and prescribed burning is necessary to remove the woody vegetation and prepare the seedbed for a successful range planting. It may be possible using selected plant materials and agronomic practices to approach something very near the functioning of State 2: Native/Invaded State. Application of chemical herbicides and the use of mechanical seeding methods using adapted varieties of the dominant native grasses are possible and can be successful. Following the establishment of the native plant species, prescribed grazing should include adequate recovery periods following each grazing event and stocking levels which match the available resources; management objectives must include the maintenance of those species, the associated reference state functions, and continued treatment of exotic grasses.

Context dependence. (i.e., factors that cause variations in plant community shifts, restoration likelihood, and contribute to uncertainty). Prescribed burning should be applied in a manner that enhances the competitive advantage of native grass and forb species over the exotic species. Prescribed burns should be applied at a frequency which mimics the natural disturbance regime or more frequently as is ecologically (e.g., available fuel load) and economically feasible. Burn prescriptions may need adjustment to: (1) account for change in fuel type (herbaceous vs. shrub vs. tree), fine fuel amount and orientation (e.g., “flopped” Kentucky bluegrass); (2) fire intensity and duration by adjusting ignition pattern (e.g., backing fires vs head fires); (3) account for plant phenological stages to maximize stress on exotic species while favoring native species (both cool- and warm-season grasses). The method of brush management will be site specific, but generally the goal would be to apply the pesticide, mechanical control, or biological control (either singularly or in combination) in a manner that shifts the competitive advantage from the targeted species to the native grasses and forbs. The control method(s) should be as specific to the targeted species as possible to minimize impacts to non-target species. A successful range planting will include proper seedbed preparation, weed control (both prior to and after the planting), selection of adapted native species representing functional/structural groups inherent to the State 1, and proper seeding technique. Management (e.g., prescribed grazing, prescribed burning) during and after establishment must be applied in a manner that maintains the competitive advantage for the seeded native species. Adding non-native species can impact the above and below ground biota. Elevated soil nitrogen levels have been shown to benefit smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass more than some native grasses. As a result, fertilization, exotic legumes in the seeding mix, and other techniques that increase soil nitrogen may promote smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass invasion.

Restoration pathway R5B

State 5 to 3

Restoration Pathway from State 5: Invaded Wooded State to State 3: Invaded State occurs with the implementation of prescribed burning and/or chemical/mechanical brush management followed by a failed range planting.

Context dependence. (i.e., factors that cause variations in plant community shifts, restoration likelihood, and contribute to uncertainty). Failed range plantings can result from many causes (both singularly and in combination) including drought, poor seedbed preparation, improper seeding methods, seeded species not adapted to the site, insufficient weed control, herbicide carryover, poor seed quality (purity & germination), and/or improper management.

Transition T6A

State 6 to 4

This is the Transition from any plant community to State 4: Go-Back State. It is most commonly associated with the cessation of cropping without the benefit of range planting, resulting in a “go-back” situation. Soil conditions can be quite variable on the site, in part due to variations in the management/cropping history (e.g., development of tillage induced compaction, erosion, fertility, and/or herbicide/pesticide carryover). Thus, soil conditions should be assessed when considering restoration techniques.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tall Warm-Season Grasses | 290–725 | ||||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 290–580 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 145–290 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 145–290 | – | ||

| 2 | Needlegrasses | 435–870 | ||||

| porcupinegrass | HESP11 | Hesperostipa spartea | 145–580 | – | ||

| green needlegrass | NAVI4 | Nassella viridula | 145–290 | – | ||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | 0–145 | – | ||

| 3 | Mid Warm-Season Grasses | 290–725 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 145–290 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 58–290 | – | ||

| prairie dropseed | SPHE | Sporobolus heterolepis | 58–290 | – | ||

| 4 | Wheatgrasses | 145–290 | ||||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 0–145 | – | ||

| slender wheatgrass | ELTR7 | Elymus trachycaulus | 29–145 | – | ||

| bearded wheatgrass | ELCA11 | Elymus caninus | 29–145 | – | ||

| 5 | Other Native Grasses | 29–145 | ||||

| Graminoid (grass or grass-like) | 2GRAM | Graminoid (grass or grass-like) | 29–145 | – | ||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 29–87 | – | ||

| mat muhly | MURI | Muhlenbergia richardsonis | 0–87 | – | ||

| Leiberg's panicum | DILE2 | Dichanthelium leibergii | 0–87 | – | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–29 | – | ||

| 6 | Grass-likes | 29–145 | ||||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 29–145 | – | ||

| long-stolon sedge | CAIN9 | Carex inops | 29–145 | – | ||

| Grass-like (not a true grass) | 2GL | Grass-like (not a true grass) | 0–145 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 7 | Forbs | 145–290 | ||||

| Forb (herbaceous, not grass nor grass-like) | 2FORB | Forb (herbaceous, not grass nor grass-like) | 29–145 | – | ||

| blazing star | LIATR | Liatris | 29–87 | – | ||

| common yarrow | ACMI2 | Achillea millefolium | 29–58 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 29–58 | – | ||

| field sagewort | ARCA12 | Artemisia campestris | 29–58 | – | ||

| white sagebrush | ARLU | Artemisia ludoviciana | 29–58 | – | ||

| false boneset | BREU | Brickellia eupatorioides | 0–58 | – | ||

| wavyleaf thistle | CIUN | Cirsium undulatum | 0–58 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | 29–58 | – | ||

| blacksamson echinacea | ECAN2 | Echinacea angustifolia | 29–58 | – | ||

| stiff sunflower | HEPA19 | Helianthus pauciflorus | 29–58 | – | ||

| stiff goldenrod | OLRI | Oligoneuron rigidum | 29–58 | – | ||

| soft-hair marbleseed | ONBEB | Onosmodium bejariense var. bejariense | 29–58 | – | ||

| silverleaf Indian breadroot | PEAR6 | Pediomelum argophyllum | 29–58 | – | ||

| upright prairie coneflower | RACO3 | Ratibida columnifera | 29–58 | – | ||

| compassplant | SILA3 | Silphium laciniatum | 0–58 | – | ||

| Canada goldenrod | SOCA6 | Solidago canadensis | 29–58 | – | ||

| white heath aster | SYER | Symphyotrichum ericoides | 29–58 | – | ||

| aromatic aster | SYOB | Symphyotrichum oblongifolium | 0–58 | – | ||

| American vetch | VIAM | Vicia americana | 29–58 | – | ||

| rush skeletonplant | LYJU | Lygodesmia juncea | 0–29 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 0–29 | – | ||

| cutleaf anemone | PUPAM | Pulsatilla patens ssp. multifida | 0–29 | – | ||

| Missouri goldenrod | SOMI2 | Solidago missouriensis | 0–29 | – | ||

| hoary verbena | VEST | Verbena stricta | 0–29 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 8 | Shrubs | 29–145 | ||||

| leadplant | AMCA6 | Amorpha canescens | 29–116 | – | ||

| prairie rose | ROAR3 | Rosa arkansana | 29–87 | – | ||

| western snowberry | SYOC | Symphoricarpos occidentalis | 29–87 | – | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–58 | – | ||

| prairie sagewort | ARFR4 | Artemisia frigida | 0–29 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Animal community - Wildlife Interpretations

Landscape

The MLRA 56A landscape is characterized by a nearly level glacial lake plain bordered on the east and west by outwash plains, till plains, gravelly beaches, and dunes. MLRA 56A is considered to have a continental climate with cold winters and hot summers, low humidity, light rainfall, and much sunshine. Extremes in temperature are common and characteristic of the MLRA. This area supports natural tall- grass prairie vegetation with bur oak, green ash, and willow growing in drainageways. This area is formed in silty and clayey lacustrine sediments from the former Glacial Lake Agassiz. Complex intermingled ecological sites create diverse grass/shrub land habitats interspersed with varying densities of linear, slope, depressional, and in-stream wetlands associated with headwater streams and tributaries to the Red River of the North. MLRA 56A is located within the boundaries of the Prairie Pothole Region and is an ecotone between the humid east and the sub-humid west regions. The primary land use is annual cropland (~80%). The Red River Valley is known for its exceptional fertility with major crops including corn, soybeans, small grains, and sugar beets.

By the mid-19th century, the majority of the Red River Valley had been converted from tall-grass prairie to annual crop production. To alleviate crop production loss from wetlands and overland flow, a system of shallow surface ditches, judicial ditches, and road ditches removes surface water in spring and during high rainfall events. The major soils are poorly drained with extensive areas of saline soils. Tile drainage systems have been or are being extensively installed throughout MLRA 56A for sub-surface field drainage to enhance annual crop production.

The east and west side of the Red River Valley formed in a complex pattern of sandy beach material, stratified inter-beach material, lacustrine silts, and lake washed glacial till. The soils vary from excessively drained on ridges to very poorly drained organic basins. Surface ditches serve to drain some of the area, although much of the area lacks adequate drainage for maximum crop production.

Calcareous fens and saline seeps can occur at the base of beach ridges and result in rare plant communities. Native vegetation was mixed- and tall-grass prairie with scattered woodland and brush.

Historic Communities/Conditions within MLRA 56A:

The northern tall- and mixed-grass prairie was a disturbance-driven ecosystem with fire, herbivory, and climate functioning as the primary ecological drivers (either singly or often in combination). Frequent and expansive flooding along the Red River and its tributaries provided abundant opportunities for Native Americans to harvest wild rice. American bison roamed MLRA 56A wintering along the Red River and migrating west into MLRA 55A and 55B for parts of the season. Many species of grassland birds, small mammals, insects, reptiles, amphibians, and large herds of roaming American bison, elk, and pronghorn were historically among the inhabitants adapted to this region. Roaming herbivores, as well as several small mammal and insect species, were the primary consumers linking the grassland resources to large predators (such as the wolf and American black bear) and smaller carnivores (such as the coyote, bobcat, red fox, and raptors). Extirpated species include free-ranging American bison and gray wolf (breeding). Extinct from the region is the Rocky Mountain locust.

Present Communities/Conditions within MLRA 56A:

MLRA 56A has the most conversion to cropland of any MLRA within Region F-Northern Great Plains. European influence has impacted remaining grassland and shrubland by domestic livestock grazing, elimination of fire, removal of surface and subsurface hydrology via artificial drainage, and other anthropogenic factors influencing plant community composition and abundance.

Extensive drainage has taken place. Streams have been straightened, removing sinuosity, and riparian zones have been converted to annual crop production. These anthropogenic impacts have reduced flood water detention and retention on the landscape, increasing storm water runoff, sediment, and nutrient loading to the Red River and its tributaries. The installation of instream structures has reduced aquatic species movement within the MLRA.

Annual cropping is the main factor contributing to habitat fragmentation, reducing habitat quality for area- sensitive species. These influences fragmented the landscape, reduced, or eliminated ecological drivers (fire), and introduced exotic species including smooth brome, Kentucky bluegrass, and leafy spurge which further impacted plant and animal communities. The loss of the bison and fire as primary ecological drivers greatly influenced the character of the remaining native plant communities and the associated wildlife, moving towards a less diverse and more homogeneous landscape.

Included in this MLRA are approximately 70,000 acres of the United States Forest Service, Sheyenne National Grassland (southern portion of MLRA) with an additional 65,000 acres of intermingled privately owned land of sandy soils providing a large tract of intact tall grass prairie within the MLRA. United Fish and Wildlife Service refuges and waterfowl production areas, along with and state wildlife management areas cover approximately 67,000 acres within the MLRA. Two of three largest cities in North Dakota are located within the MLRA.