Ecological dynamics

U.S. National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) that are consistent with reference conditions on this ecological site include CEGL007237 Quercus rubra - Quercus alba - Carya glabra / Geranium maculatum. On north-facing or sheltered lower slopes, CEGL008465 Fagus grandifolia - Quercus rubra / Cornus florida / Polystichum acrostichoides - Hexastylis virginica may apply (USNVC 2022).

MATURE FORESTS

The reference state supports a closed to somewhat open canopy forest dominated by mesophytic and dry-mesophytic oaks, with a smaller contribution from bottomland oaks, hickories, and pines. Old-growth stands are uncommon.

Under reference conditions, oaks are dominant in the canopy. Representative species include white oak (Quercus alba) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra). The hickory component is of much lower cover. Pignut hickory (Carya glabra) and mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa) are typically most abundant. Hickories tend to be much more abundant in the understory. Bottomland oaks that frequent the canopy include willow oak (Quercus phellos) and water oak (Quercus nigra). These species are usually of relatively low cover in the canopy but can be abundant in the understory, especially under fire-suppressed conditions.

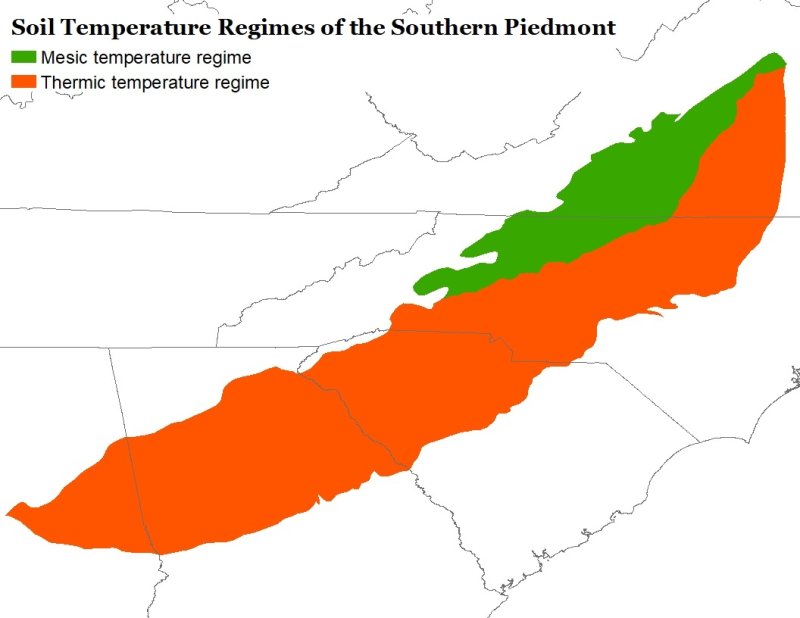

In mature stands, pines are typically scattered throughout the forest. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) and shortleaf pine (P. echinata) are the principle species in most of the thermic soil temperature regime portion of the MLRA. According to historical accounts and witness tree records, the importance of the pine component naturally increases, though very gradually, from north to south. Prior to the European settlement, loblolly pine was largely confined to drainageways and adjacent lower slopes in the uplands of the Southern Piedmont. In the past, loblolly pine would have likely made a larger contribution to the pine component on this ecological site than on higher and drier ecological site concepts.

American beech (Fagus grandifolia) is another notable but relatively minor canopy species of mature stands associated with this ecological site. On north-facing slopes it can be an important canopy species, but otherwise it tends to be more important in the understory. Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), though more abundant in the early stages of succession, is also characteristic of mature stands. Like the pine species, it is usually of low cover, colonizing and reproducing chiefly in canopy gaps.

In addition to the forenamed species, other characteristic species of the subcanopy layer include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), red maple (Acer rubrum), common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), and sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum).

The shrub and herb layers are dominated by acid-loving flora, including those of the heath family, however the shrub and herb layers are less acidic in character than in drier and more infertile acidic uplands. Under reference conditions, the shrub layer is typically sparse, with seedlings and saplings of canopy species, or vines, occupying much of the cover.

Characteristic shrub species include American holly (Ilex opaca), bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium), and several blueberry species (Vaccinium spp.). Characteristic vines include Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), roundleaf greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), and muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia).

Although the herb layer is generally sparse, it can be impressively species-rich under reference conditions, especially where fire has been reintroduced. Low species richness is often the result of long-term overgrazing by large deer populations. Species richness can be increased through effective deer population management, as well as through the reintroduction of regular, low-intensity ground fires.

Common herbaceous species include Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), littlebrownjug (Hexastylis arifolia), crippled cranefly (Tipularia discolor), dimpled troutlily (Erythronium umbilicatum), nakedflower ticktrefoil (Desmodium nudiflorum), Virginia snakeroot (Aristolochia serpentaria), and partridgeberry (Mitchella repens). Additional species representative of fire-maintained stands include hairy bedstraw (Galium pilosum), woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus), several species of lespedeza (Lespedeza spp.) and ticktrefoil (Desmodium spp.), and an array of grasses and sedges.

DYNAMICS OF NATURAL SUCCESSION AND FIRE ECOLOGY

On Piedmont uplands, the historical influence of fire on successional dynamics was likely expressed on a continuum, from dry to moist, where moist or sheltered sites were shaped more by gap-driven dynamics and dry or exposed sites more by fire. On intermediate sites, their respective influence on successional dynamics probably fell somewhere in between. While the historic fire return interval is thought to be relatively similar across most of the Southern Piedmont uplands, moister sites were less prone to fire and hence burned less completely and at lower intensities than drier sites.

Like other moist oak-hickory forests in the region, successional dynamics are thought to be primarily gap-driven, with small-scale natural disturbances such as windthrow, drought, and disease, usually affecting only small portions of the forest at a time. Canopy gaps are readily colonized by early successional herbs and shrubs, and later by pines and opportunistic hardwoods. These localized events are inconspicuous, but cumulatively they help shape the age class distribution, structure, and species composition in these forests.

In the past, regular low-intensity fires would have kept the understory somewhat more open than at present and constrained the growth of fire-intolerant woody species. Periodic severe fires would have likely occurred during unusually dry and windy conditions, presumably resulting in catastrophic tree mortality and stand replacing changes. The reduction in the frequency of fires over the past century has allowed shade-tolerant, fire-sensitive trees such as red maple (Acer rubrum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), and American holly (Ilex opaca) to become more abundant in many upland forests in the Southeast. These species are all expected components of the subcanopy on this ecological site, but they have proliferated in the absence of fire.

A combination of prescribed burns and selective removals can open up the understory and constrain the growth of fire-intolerant opportunistic species, thereby restoring the health and vigor of forests that evolved under a more regular fire regime.

YOUNG SECONDARY FORESTS

On relatively undisturbed sites, stands are uneven-aged, with at least some old trees present. In areas that were cultivated in the recent past, even-aged pine stands dominate the landscape, being replaced by oaks and hickories only as the pines die.

In general, young secondary forests on this ecological site are dominated by loblolly pine (P. taeda), along with opportunistic hardwoods such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), red maple (Acer rubrum), and tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera). Oaks and hickories are usually confined to the understory of young secondary stands. Their growth is temporarily suppressed by the cover of faster growing tree species.

In the central Piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia, Virginia pine (P. virginiana) becomes increasingly important in young secondary stands, particularly in the Carolina Slate Belt and even more so in regions to the west or north. In regions further south, loblolly pine is typically the more competitive pioneer under most site conditions, apart from higher elevation areas of the upper Piedmont where Virginia pine becomes more abundant.

Under a canopy of pines, a shift toward dry-site understory species is often observed. In the Southern Piedmont, old-field pine stands typically exhibit a sparse, xerophytic herb-shrub stratum, resulting from intense competition with the dominant pines, whose roots form a closed network within the upper few inches of soil. Low levels of sunlight and a thick layer of pine litter on the forest floor further suppress herb and shrub development. In such an environment, striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), blueberry (Vaccinium sp.), and various other members of the heath family are well-adapted for survival (Billings 1938; Oosting 1942; Nelson 1957; Wharton 1978; Golden 1979; Barry 1980; Peet and Christensen 1980, 1987; Skeen et al. 1980; Felix III et al. 1983; Nelson 1986; Schafale and Weakley 1990; Cowell 1998; Spira 2011; Spooner et al. 2021; Fleming 2012; Guyette et al. 2012; Schafale 2012a, 2012b; Edwards et al. 2013; Vander Yacht et al. 2020; Fleming et al. 2021; Greenberg et al. 2021).

SPECIES LIST

Canopy layer: Quercus alba, Quercus rubra, Carya glabra, Carya tomentosa, Quercus phellos, Quercus nigra, Pinus taeda, Pinus echinata, Quercus falcata, Fagus grandifolia, Liriodendron tulipifera

Subcanopy layer: Cornus florida, Nyssa sylvatica, Acer rubrum, Carya spp., Quercus phellos, Quercus nigra, Diospyros virginiana, Fagus grandifolia, Ilex opaca, Prunus serotina, Oxydendrum arboreum, Sassafras albidum, Fraxinus americana, Liquidambar styraciflua,

Vines/lianas: Parthenocissus quinquefolia, Smilax rotundifolia, Campsis radicans, Vitis rotundifolia, Toxicodendron radicans, Gelsemium sempervirens, Loncera japonica (I),

Shrub layer: Ilex opaca, Euonymus americanus, Viburnum prunifolium, Vaccinium spp., Ligustrum sinense (I), Elaeagnus umbellata (I),

Herb layer - forbs: Polystichum acrostichoides, Hexastylis arifolia, Asplenium platyneuron, Tipularia discolor, Erythronium umbilicatum, Desmodium nudiflorum, Aristolochia serpentaria, Mitchella repens, Elephantopus carolinianus, Elephantopus tomentosus, Ruellia caroliniensis, Galium pilosum, Helianthus divaricatus, Verbena urticifolia, Geranium maculatum, Sanguinaria canadensis, Goodyera pubescens, Uvularia perfoliata, Geum canadense, Agrimonia parviflora, Oxalis violacea, Podophyllum peltatum, Lycopodium digitatum, Hypoxis hirsuta, Stellaria pubera, Galium circaezans,

Herb layer - graminoids: Dichanthelium spp., Carex spp. (cephalophora, digitalis, hirsutella, laxiflora, radiata), Luzula echinata, Microstegium vimineum (I)

(I) = introduced

State 1

Reference State

This mature forest state is generally dominated by mesophytic and dry-mesophytic upland oaks, with a smaller contribution from bottomland oaks, hickories, and pines.

Characteristics and indicators. Stands are uneven-aged with at least some old trees present.

Resilience management. Deer population management is critical to sustaining the diversity of herbaceous understory species.

Community 1.1

Seasonally Wet Acidic Oak-Hickory Forest - Fire Maintained Phase

This is a closed to somewhat open canopy mature forest community/phase. Regular low-intensity fires have been reintroduced, keeping the understory somewhat open, increasing the cover and diversity of herbaceous species and limiting the importance of fire-intolerant woody species.

Resilience management. This community/phase is maintained through regular prescribed burns. The recruitment of fire-adapted oaks and pines benefits from regular low-intensity ground fires, as these forests evolved under a more regular fire regime. Tree ring data suggests that the mean fire return interval of the past in the Southern Piedmont is approximately 6 years, though the actual return interval varied from 3 to 16 years. To approximate the pre-colonial fire regime, prescribed burns should be carried out every 4 to 8 years.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by upland oaks. Representative species include white oak (Quercus alba) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Hickories make a smaller contribution to the canopy (Carya glabra, C. tomentosa, C. ovalis), along with scattered pines (Pinus spp.). Bottomland oaks that may be present in the canopy include willow oak (Quercus phellos) and water oak (Quercus nigra). These species are usually not abundant in fire-maintained stands.

Forest understory. Representative understory tree species include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), and hickory (Carya spp.).

Fire-sensitive tree species such as American beech (Fagus grandifolia), red maple (Acer rubrum), willow oak (Quercus phellos), and water oak (Quercus nigra) may be present, but they are usually less abundant in fire maintained stands.

Representative understory shrub species include American holly (Ilex opaca), bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), and several blueberry species (Vaccinium spp.).

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

northern red oak (Quercus rubra), tree

-

pignut hickory (Carya glabra), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

willow oak (Quercus phellos), tree

-

water oak (Quercus nigra), tree

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), shrub

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

oval-leaf sedge (Carex cephalophora), grass

-

slender woodland sedge (Carex digitalis), grass

-

fuzzy wuzzy sedge (Carex hirsutella), grass

-

splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternarius), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), grass

-

hedgehog woodrush (Luzula echinata), grass

-

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), other herbaceous

-

littlebrownjug (Hexastylis arifolia), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

crippled cranefly (Tipularia discolor), other herbaceous

-

dimpled troutlily (Erythronium umbilicatum), other herbaceous

-

nakedflower ticktrefoil (Desmodium nudiflorum), other herbaceous

-

Virginia snakeroot (Aristolochia serpentaria), other herbaceous

-

Carolina elephantsfoot (Elephantopus carolinianus), other herbaceous

-

Carolina wild petunia (Ruellia caroliniensis), other herbaceous

-

hairy bedstraw (Galium pilosum), other herbaceous

Community 1.2

Seasonally Wet Acidic Oak-Hickory Forest - Fire Suppressed Phase

This is a closed canopy mature forest community/phase. This phase accounts for the majority of contemporary examples. Canopy cover is higher than in stands in which fire has been reintroduced. The pine component can have a greater proportion of loblolly or Virginia pine and the understory usually contains a greater proportion of fire-intolerant species. The herbaceous understory is typically sparse.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by upland oaks. Representative species include white oak (Quercus alba) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Bottomland oaks, hickories, and pines make a smaller contribution to the canopy. Representative hickory species include pignut hickory (Carya glabra) and mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa). Bottomland oaks, such as willow oak (Quercus phellos) and water oak (Quercus nigra), usually occupy some portion of the canopy cover.

Forest understory. Representative understory tree species include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), and hickory (Carya spp.), along with fire-sensitive species such as American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American holly (Ilex opaca), red maple (Acer rubrum), willow oak (Quercus phellos), and water oak (Quercus nigra).

Representative understory shrub species include American holly (Ilex opaca), bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium), and several blueberry species (Vaccinium spp.).

The herb layer is sparser and less diverse than in the fire maintained phase.

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

northern red oak (Quercus rubra), tree

-

pignut hickory (Carya glabra), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

willow oak (Quercus phellos), tree

-

water oak (Quercus nigra), tree

-

American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), shrub

-

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), shrub

-

roundleaf greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), shrub

-

trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium), shrub

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

oval-leaf sedge (Carex cephalophora), grass

-

slender woodland sedge (Carex digitalis), grass

-

fuzzy wuzzy sedge (Carex hirsutella), grass

-

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), other herbaceous

-

littlebrownjug (Hexastylis arifolia), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

crippled cranefly (Tipularia discolor), other herbaceous

-

dimpled troutlily (Erythronium umbilicatum), other herbaceous

-

partridgeberry (Mitchella repens), other herbaceous

-

nakedflower ticktrefoil (Desmodium nudiflorum), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Long-term exclusion of fire causes an increase in fire-intolerant understory species and a deterioration of the abundance and diversity of herbaceous species.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

The fire suppressed phase can be managed towards the fire maintained phase through a combination of prescribed burns and selective removals. To approximate the pre-colonial fire regime, prescribed burns should be carried out every 4 to 8 years.

Context dependence. After decades of fire suppression, most upland hardwood forests of the Southeast have undergone mesophication, or succession toward forest systems that are less apt to burn. If prescribed fire is to be used as a management tool in fire suppressed ecosystems of the Piedmont, planning will be needed in some forest systems to overcome the effects of mesophication in the early stages of fire reintroduction.

State 2

Secondary Succession State

This state develops in the immediate aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clearcut logging, or other large-scale disturbances that lead to canopy removal. Which species colonize a particular location in the wake of a disturbance does involve a considerable degree of chance. It also depends a great deal on the type, duration, and magnitude of the disturbance event.

Characteristics and indicators. Plant age distribution is even. Plants exhibit pioneering traits such as rapid growth, early reproduction, and shade-intolerance.

Community 2.1

Old-field Pine-Hardwood Forest Phase

This forested successional phase develops in the wake of long-term agricultural abandonment or other large-scale disturbances that have led to canopy removal in the recent past. Stands are even-aged and species diversity is low. The canopy is usually dominated by pines, though opportunistic hardwoods can also be important, particularly in the early stages of tree establishment. Species that exhibit pioneering traits are usually most abundant.

Forest overstory. The overstory is typically dominated by pines. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) is the most characteristic species, followed by shortleaf pine (P. echinata), and to the north and west Virginia pine (P. virginiana). Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera) can also be an important tree species, at times dominating the canopy layer in young secondary stands.

Forest understory. Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) is the most representative understory tree species, though its importance tends to decline as the pines mature. Other common species include red maple (Acer rubrum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American holly (Ilex opaca), and white ash (Fraxinus americana). Seedlings of oaks and hickories are usually present in the understory. These seedlings are released gradually as the forest matures and the pines begin to die off.

In the shrub layer, representative species include American holly (Ilex opaca), various blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), and several vines.

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tree

-

tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), tree

-

white ash (Fraxinus americana), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

hybrid hickory (Carya), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

roundleaf greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), shrub

-

Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), shrub

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), shrub

-

littlehead nutrush (Scleria oligantha), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

wild garlic (Allium vineale), other herbaceous

-

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), other herbaceous

-

fan clubmoss (Lycopodium digitatum), other herbaceous

-

sparselobe grapefern (Botrychium biternatum), other herbaceous

-

partridgeberry (Mitchella repens), other herbaceous

Community 2.2

Shrub-dominated Successional Phase

This successional phase is dominated by shrubs and vines, along with seedlings of opportunistic hardwoods and pines. It typically develops beginning in the third year after agricultural abandonment or clearcut logging. It grades into the forested successional phase as tree seedlings become saplings and begin to occupy more of the canopy cover.

Forest overstory. Species composition varies considerably from location to location. Non-native species usually occupy some portion of the vine or shrub cover in most examples.

Dominant plant species

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

winged elm (Ulmus alata), tree

-

tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), tree

-

Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), tree

-

Chinaberrytree (Melia azedarach), tree

-

white ash (Fraxinus americana), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

eastern baccharis (Baccharis halimifolia), shrub

-

trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), shrub

-

sweet autumn virginsbower (Clematis terniflora), shrub

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

velvet panicum (Dichanthelium scoparium), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

Canada goldenrod (Solidago altissima), other herbaceous

-

dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

Indianhemp (Apocynum cannabinum), other herbaceous

-

yellow crownbeard (Verbesina occidentalis), other herbaceous

Community 2.3

Herbaceous Early Successional Phase

This transient community is composed of the first herbaceous invaders in the aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clearcut logging, or other large-scale natural disturbances that lead to canopy removal.

Species composition is highly variable at this stage of succession. In addition to the named species, other herbaceous pioneers common to this ecological site include wild lettuce (Lactuca spp.), fleabane (Erigeron spp.), Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), vetch (Vicia spp.), yellow crownbeard (Verbesina occidentalis), Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota), evening primrose (Oenothera spp.), Indianhemp (Apocynum cannabinum), slender yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis dillenii), cudweed (Pseudognaphalium spp.), Brazilian vervain (Verbena brasiliensis), morning-glory (Ipomoea spp.), garden cornflower (Centaurea cyanus), common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), Indian-tobacco (Lobelia inflata), spiny sowthistle (Sonchus asper), several species of thoroughwort (Eupatorium spp.), and many others.

Resilience management. If the user wishes to maintain this community/phase for wildlife or pollinator habitat, a prescribed burn, mowing, or prescribed grazing will be needed at least once annually to prevent community pathway 2.3A. To that end, as part of long-term maintenance, periodic overseeding of wildlife or pollinator seed mixtures can be helpful in ensuring the viability of certain desired species and maintaining the desired composition of species for user goals.

Dominant plant species

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), shrub

-

eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), shrub

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), grass

-

southern crabgrass (Digitaria ciliaris), grass

-

smooth crabgrass (Digitaria ischaemum), grass

-

Japanese bristlegrass (Setaria faberi), grass

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

annual bluegrass (Poa annua), grass

-

small carpetgrass (Arthraxon hispidus), grass

-

American burnweed (Erechtites hieraciifolius), other herbaceous

-

American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), other herbaceous

-

Canada goldenrod (Solidago altissima), other herbaceous

-

beggarticks (Bidens), other herbaceous

-

annual ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), other herbaceous

-

knotweed (Polygonum), other herbaceous

-

dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis), other herbaceous

-

bitter dock (Rumex obtusifolius), other herbaceous

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.3

The old-field pine-hardwood forest phase can return to the herbaceous early successional phase through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Context dependence. Note: if the user wishes to use this community pathway to create wildlife or pollinator habitat, please contact a local NRCS office for a species list specific to the area of interest and user needs.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

The shrub-dominated successional phase naturally moves towards the old-field pine-hardwood forest through natural succession.

Pathway 2.2B

Community 2.2 to 2.3

The shrub-dominated successional phase can return to the herbaceous early successional phase through brush management, including herbicide application, mechanical removal, prescribed grazing, or fire.

Context dependence. Note: if the user wishes to use this community pathway to create wildlife or pollinator habitat, please contact a local NRCS office for a species list specific to the area of interest and user needs.

If the user wishes to maintain the shrub-dominated successional phase long term, for wildlife habitat or other uses, periodic use of this community pathway is necessary to prevent community pathway 2.2A, which happens inevitably unless natural succession is set back through disturbance.

Pathway 2.3A

Community 2.3 to 2.2

The herbaceous early successional phase naturally moves towards the shrub-dominated successional phase through natural succession. The process takes approximately 3 years on average, barring any major disturbances capable of inhibiting natural succession.

State 3

High-graded Hardwood Forest State

This state develops as a consequence of high-grading, where the most valuable trees are removed, leaving less desirable timber specimens behind. Trees left behind include undesirable timber species, trees of poor form, diseased trees, or genetically inferior trees.

Characteristics and indicators. Typically, high-graded stands consist of a combination of residual stems from the previous stand, a high proportion of undesirable shade-tolerant species, along with some regrowth from desirable timber species. In some cases, large-diameter trees of desirable timber species may be present, but upon closer inspection, these trees usually have serious defects that resulted in their being left behind in earlier cuts.

Resilience management. Landowners with high-graded stands have two options for improving timber production: 1) rehabilitate, or 2) regenerate. To rehabilitate a stand, the landowner must evaluate existing trees to determine if rehabilitation is justified. If the proportion of high-quality specimens present in the stand is low, then the stand should be regenerated. In many cases, poor quality of the existing stand is the result of decades of mismanagement. Drastic measures are often required to get the stand back into good timber production.

State 4

Managed Pine Plantation State

This converted state is dominated by planted timber trees. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) is the most commonly planted species. Even-aged management is the most common timber management system.

Note: if the user wishes to convert stands dominated by hardwoods to planted pine, clearcutting will usually be necessary first, allowing herbaceous pioneers to establish on the site in the weeks or months prior to planting. Users should utilize measures described in transition T2B under these circumstances.

Resilience management. Hardwood Encroachment:

Hardwood encroachment can be problematic in managed pine plantations. Good site preparation, proper stocking, and periodic thinning are advisable to reduce hardwood competition.

Overstocking:

The overstocked condition commonly occurs in naturally regenerated stands. When competition from other pines begins to impact the health and productivity of the stand, precommercial thinning should be considered. At this point, the benefit of thinning usually outweighs the potential for invasion and competition from non-pine species. As the target window for thinning passes, the condition of the stand can slowly deteriorate if no action is taken. Under long-term overstocked conditions, trees are more prone to stresses, including pine bark beetle infestation and damage from wind or ice.

High-grading:

In subsequent commercial thinnings, care should be taken in tree selection. High quality specimens should be left to reach maturity, while slower growing trees or those with defects should be removed sooner. If high quality specimens are harvested first, trees left behind are often structurally unsound, diseased, genetically inferior, or of poor form. This can have long-term implications for tree genetics and for the condition of the stand (Felix III 1983; Miller et al. 1995, 2003; Megalos 2019).

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

hybrid hickory (Carya), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

grape (Vitis), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

littlehead nutrush (Scleria oligantha), grass

-

longleaf woodoats (Chasmanthium sessiliflorum), grass

-

sortbeard plumegrass (Saccharum brevibarbe var. contortum), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), other herbaceous

-

fan clubmoss (Lycopodium digitatum), other herbaceous

State 5

Pasture/Hayland State

This converted state is dominated by herbaceous forage species.

Resilience management. Overgrazing and High Foot Traffic:

In areas that are subject to high foot traffic from livestock and equipment, and/or long-term overgrazing, unpalatable weedy species tend to invade, as most desirable forage species are less competitive under these conditions. High risk areas include locations where livestock congregate for water, shade, or feed, and in travel lanes, gates, and other areas of heavy use. Plant species that are indicative of overgrazing or excessive foot traffic on this ecological site include buttercup (Ranunculus spp.), plantain (Plantago spp.), curly dock (Rumex crispus), sneezeweed (Helenium amarum), cudweed (Pseudognaphalium spp.), slender yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis dillenii), Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), Virginia pepperweed (Lepidium virginicum), black medick (Medicago lupulina), annual bluegrass (Poa annua), poverty rush (Juncus tenuis), and Indian goosegrass (Eleusine indica), among others. A handful of desirable forage species are also tolerant of heavy grazing and high foot traffic, including white clover (Trifolium repens), dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), and bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon). An overabundance of these species, along with poor plant vigor and areas of bare soil, may imply that excessive foot traffic and/or overgrazing is a concern, either in the present or in the recent past.

Soil Fertility and pH Management:

Like overgrazing and excessive foot traffic, inadequate soil fertility and pH management can lead to invasion from several common weeds of pastures and hayfields. Species indicative of poor soil fertility and/or suboptimal pH on this ecological site include broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), sweet vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), common sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), among others. Most of these weedy invaders do not compete well in dense, rapidly growing pastures and hayfields. By maintaining soil fertility and pH, managing grazing to favor desirable forage species, and clipping behind grazing rotations when needed, forage grasses and forbs can usually outcompete weedy invaders.

Brush Encroachment:

Brush encroachment can be problematic in some pastures, particularly near fence lines where there is often a ready seed source. Pastures subject to low stocking density and long-duration grazing rotations can also be susceptible to encroachment from woody plants. Shorter grazing rotations of higher stocking density can help alleviate pressure from shrubs and vines with low palatability or thorny stems. Clipping behind grazing rotations, annual brush hogging, and multispecies grazing systems (cattle with or followed by goats) can also be helpful. Common woody invaders of pasture on this ecological site include rose (Rosa spp.), blackberry (Rubus spp.), saw greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), black cherry (Prunus serotina), and Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense).

Dominant plant species

-

tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), grass

-

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), grass

-

orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata), grass

-

dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), grass

-

perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), grass

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), grass

-

purpletop tridens (Tridens flavus), grass

-

bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

sweet vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), grass

-

white clover (Trifolium repens), other herbaceous

-

red clover (Trifolium pratense), other herbaceous

-

vetch (Vicia), other herbaceous

-

narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata), other herbaceous

-

dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), other herbaceous

-

field clover (Trifolium campestre), other herbaceous

-

black medick (Medicago lupulina), other herbaceous

-

common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), other herbaceous

-

wild garlic (Allium vineale), other herbaceous

State 6

Cropland State

This converted state produces food or fiber for human uses. It is dominated by domesticated crop species, along with typical weedy invaders of cropland.

Community 6.1

Conservation-management Cropland Phase

This cropland phase is characterized by the practice of no-tillage or strip-tillage, and other soil conservation practices. Though no-till systems offer many benefits, several weedy species tend to be more problematic under this type of management system. In contrast with conventional tillage systems, problematic species in no-till systems include biennial or perennial weeds, owing to the fact that tillage is no longer used in weed management.

Community 6.2

Conventional-management Cropland Phase

This cropland phase is characterized by the recurrent use of tillage as a management tool. Due to the frequent disturbance regime, weedy invaders tend to be annual herbaceous species that reproduce quickly and are prolific seed producers.

Resilience management. The potential for soil loss is high under this management system. Measures should be put in place to limit erosion.

Pathway 6.1A

Community 6.1 to 6.2

The conservation-management cropland phase can shift to the conventional-management cropland phase through cessation of conservation tillage practices and the reintroduction of conventional tillage practices.

Context dependence. Soil and vegetation changes associated with this community pathway typically occur several years after reintroduction of conventional tillage practices. These changes continue to manifest as conventional tillage is continued, before reaching a steady state.

Pathway 6.2A

Community 6.2 to 6.1

The conventional-management cropland phase can be brought into the conservation-management cropland phase through the implementation of one of several conservation tillage options, including no-tillage or strip-tillage, along with implementation of other soil conservation practices.

Context dependence. Soil and vegetation changes associated with this community pathway typically occur several years after implementation of conservation tillage. These changes continue to manifest as conservation tillage is continued, before reaching a steady state.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

The reference state can transition to the secondary succession state through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The reference state can transition to the high-graded hardwood forest state through selective removal of the most valuable trees, leaving undesirable timber specimens behind. This may occur through multiple cutting cycles over the course of decades or longer, each cut progressively worsening the condition of the stand.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 5

The reference state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T1D

State 1 to 6

The reference state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 1

The secondary succession state can transition to the reference state through long-term natural succession. This process can be accelerated to some degree by a combination of prescribed burns and selective harvesting of pines and opportunistic hardwoods.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

The secondary succession state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and planting of timber trees. Thinning alone may be sufficient for portions of the forest if pines have already established, though it is rarely sufficient for an entire forest patch.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

The secondary succession state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning wooded or semi-wooded land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T2D

State 2 to 6

The secondary succession state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) weed control, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking may be needed to successfully transition land that has been fallow for some time back to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the secondary succession state through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Transition T3C

State 3 to 5

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T3D

State 3 to 6

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) herbicide application, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the secondary succession state through abandonment of forestry practices (with or without timber tree harvest).

Transition T4B

State 4 to 5

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical stump and debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Applications of fertilizer and lime can be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T4C

State 4 to 6

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the cropland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical stump and debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, 5) herbicide application, 6) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the secondary succession state through long-term cessation of grazing.

Transition T5B

State 5 to 4

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and tree planting.

Transition T5C

State 5 to 6

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the cropland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) applications of fertilizer/lime, 3) herbicide application, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T6A

State 6 to 2

The cropland state can transition to the secondary succession state through agricultural abandonment.

Transition T6B

State 6 to 4

The cropland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and tree planting.

Transition T6C

State 6 to 5

The cropland state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) weed control, and 3) planting of perennial forage grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. To convert cropland to pasture or hayland, weed control and good seed-soil contact are important. It is also critical to review the labels of herbicides used for weed control and on the previous crop. Many herbicides have plant-back restrictions, which if not followed could carryover and kill forage seedlings as they germinate. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.