Ecological dynamics

No closely related U.S. National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) associations apply to this ecological site concept. Overlapping associations include CEGL004910 Quercus montana - Quercus stellata - Pinus echinata / Vaccinium pallidum / Schizachyrium scoparium, CEGL007096 Pinus echinata - Quercus alba - Quercus stellata / Vaccinium pallidum, and CEGL008427 Pinus echinata - Quercus alba / Vaccinium pallidum / Hexastylis arifolia - Chimaphila maculata (USNVC 2022).

MATURE FORESTS

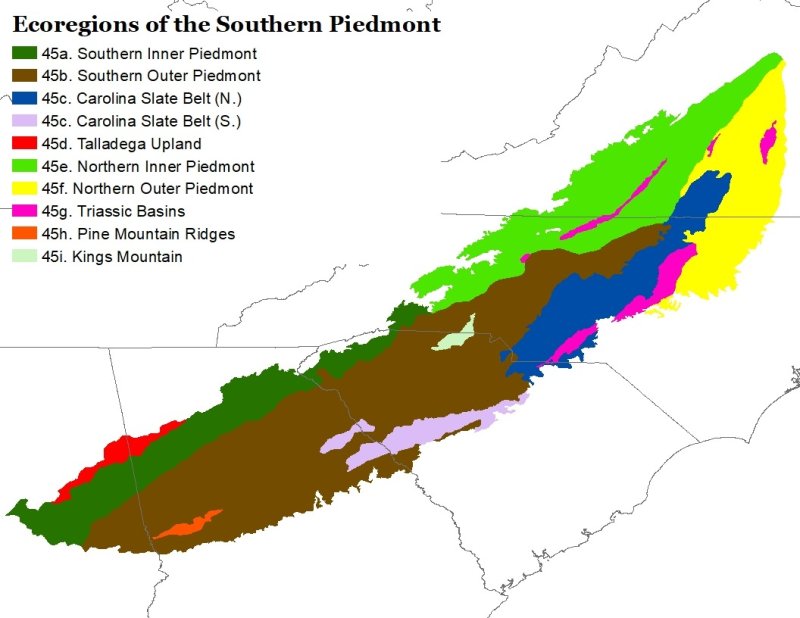

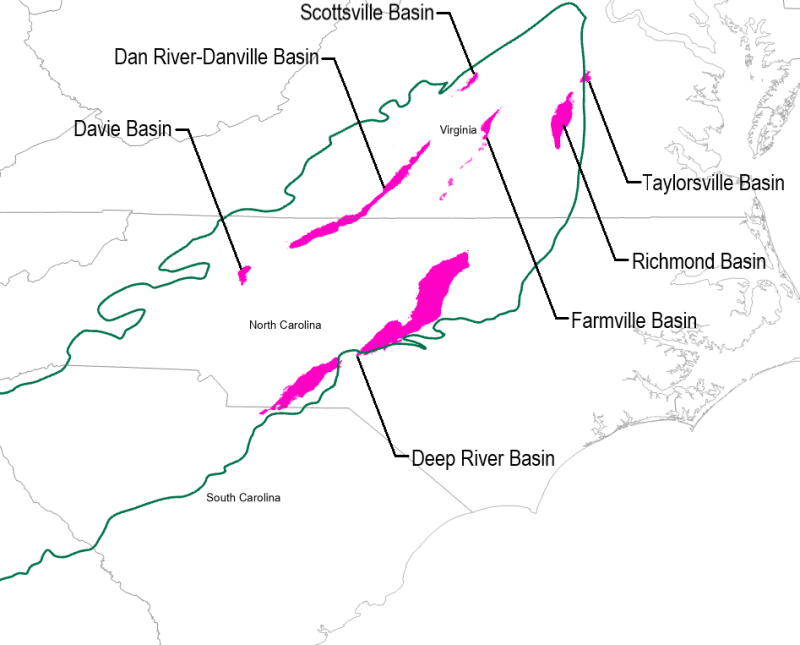

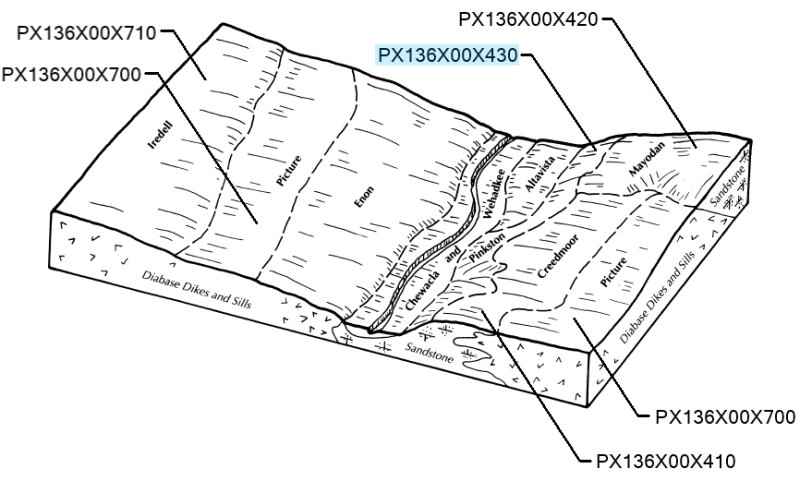

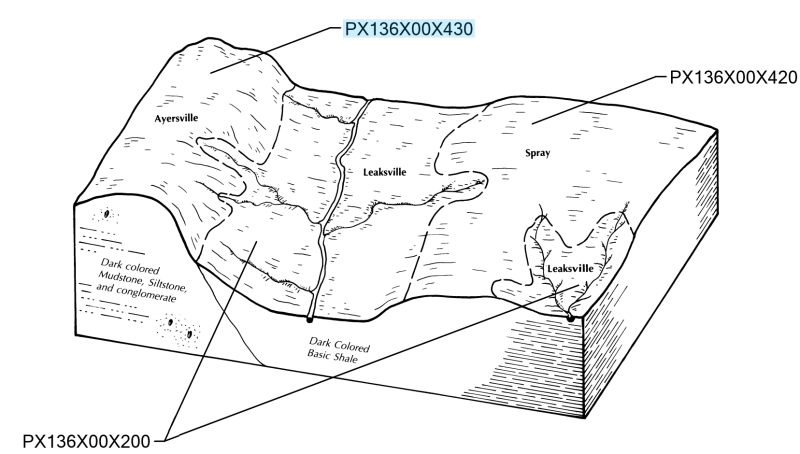

The reference state typically has a somewhat open tree canopy dominated by dry-site oaks, or a mixture of dry-site oaks and pines. Canopy cover was presumably more open in the past. Dominant canopy species include post oak (Quercus stellata) and white oak (Quercus alba), with pines (P. echinata, P. taeda, P. virginiana) interspersed. Shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) is particularly important in dry, nutrient-poor uplands of the Triassic Basins, and was likely the dominant pine species over most of the region in the past. Other characteristic species of the canopy layer include black oak (Quercus velutina) and southern red oak (Quercus falcata). In the Dan River-Danville Triassic Basin, where a system of low ridges runs the length of the basin, chestnut oak (Quercus montana) and Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) can be important species.

The understory is occupied by acid-loving plant species. In the subcanopy, characteristic species include blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), and flowering dogwood (Cornus florida). The shrub layer is dominated by members of heath family, including deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata). Farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum) can be an important species in the southern part of the extent, decreasing gradually to the north.

As a result of decades of fire suppression, the herb layer is generally sparse and species-poor, with true herbaceous species usually being poorly represented in most contemporary stands. Representative species under fire-suppressed conditions include striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), rattlesnakeweed (Hieracium venosum), ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), and trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens). Under the influence of fire, the herb layer would presumably be denser and more diverse, including an array of grasses, leguminous forbs, and composites.

DYNAMICS OF NATURAL SUCCESSION AND FIRE ECOLOGY

Historically, oak and oak-pine forests of the Southeast were maintained through recurring fire, either naturally-occurring or introduced by humans. Beginning in the early 20th century, a widespread fire suppression campaign resulted in a dramatic decrease in the frequency of fires across the Southeast. These changes gradually altered the vegetation structure and species composition of ecosystems that were dependent on fire for seedling recruitment, reproduction, and maintenance.

On Piedmont uplands, the historical influence of fire on successional dynamics was likely expressed on a continuum, from dry to moist, where moist or sheltered sites were shaped more by gap-driven dynamics and dry or exposed sites more by fire. On intermediate sites, their respective influence on successional dynamics probably fell somewhere in between.

In contemporary upland forests of the Southern Piedmont, an overall shift towards gap-driven successional dynamics (driven largely by windthrow, drought, disease, etc.) has had a homogenizing effect on the upland vegetation of the region, making moist, intermediate, and dry sites more similar to one another than they were in the past.

On this ecological site, contemporary examples tend to have a thick layer of leaf litter and fewer understory grasses and forbs. Dense colonies of ericaceous (heath family) shrubs, vines, and small trees have often grown up in the understory, restricting the growth of true herbaceous species. Over years of fire exclusion, these characteristics have often progressed to such a degree that conditions are no longer conducive to the spread of fire, a phenomenon known as mesophication. In this scenario, when fire is removed for long periods of time, positive feedbacks result in succession toward forest systems that are less apt to burn.

In the past, the routine use of fire by Native Americans, coupled with periodic lightning-induced fires, constrained the growth of understory shrubs and fire-intolerant trees. These fires maintained a more open canopy and promoted a dense herbaceous layer that could efficiently carry fire in future burns. While the historic fire return interval is thought to be relatively similar across most of the Southern Piedmont uplands, drier sites were more prone to fire and hence burned more completely and at higher intensities than moister sites.

Vegetation structure was historically more open throughout the Southern Piedmont uplands, but particularly on drier or more exposed sites. Given the more frequent fire regime of the past, canopy cover was likely more open and more heterogeneous than it is presently, and herb cover higher overall, as per historical accounts and witness tree records.

On the driest uplands of the Piedmont, all but the most fire-tolerant tree species would have been suppressed, and some excluded entirely. Those species with intermediate fire tolerance, including some oaks, pines, and hickories, would have presumably been more abundant on moister or more sheltered sites.

The reduction in the frequency of fires over the past century has allowed shade-tolerant, fire-sensitive trees such as red maple (Acer rubrum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), and American holly (Ilex opaca) to become more abundant in many upland forests in the Southeast, but they are particularly out of place on dry uplands. Except for in sheltered areas, these thin-barked species would have been largely excluded from the understory of dry upland forests under a more frequent fire regime.

A combination of prescribed burns and selective removals can open up the understory and constrain the growth of fire-intolerant opportunistic species, thereby restoring the health and vigor of forests that evolved under a more regular fire regime (Pinchot and Ashe 1897; Oosting 1942; Peet and Christensen 1980; Schafale and Weakley 1990; White and Lloyd 1998; Schwartz et al. 2007; Spira 2011; Fleming 2012; Guyette et al. 2012; Schafale 2012a, 2012b; Vander Yacht et al. 2020; Fleming et al. 2021; Greenberg et al. 2021; Spooner et al. 2021).

SPECIES LIST

Canopy layer: Quercus stellata, Quercus alba, Pinus echinata, Quercus velutina, Quercus falcata, Quercus montana, Pinus virginiana, Pinus taeda, Quercus marilandica, Carya tomentosa,

Subcanopy layer: Nyssa sylvatica, Sassafras albidum, Oxydendrum arboreum, Cornus florida, Chionanthus virginicus, Diospyros virginiana, Carya tomentosa, Acer rubrum, Fagus grandifolia, Prunus serotina, Juniperus virginiana

Shrub layer: Vaccinium stamineum, Vaccinium pallidum, Vaccinium tenellum, Vaccinium arboreum, Sassafras albidum, Hypericum hypericoides ssp. multicaule, Gaylussacia baccata, Viburnum acerifolium, Ceanothus americanus, Rosa carolina, Ilex ambigua,

Vines/lianas: Vitis rotundifolia, Smilax glauca, Smilax bona-nox, Vitis aestivalis, Smilax rotundifolia, Lonicera sempervirens, Lonicera japonica (I)

Herb layer: Pteridium aquilinum, Chimaphila maculata, Asplenium platyneuron, Epigaea repens, Lespedeza hirta, Lespedeza virginica, Lespedeza repens, Desmodium laevigatum, Solidago odora, Cunila origanoides, Hieracium gronovii, Antennaria plantaginifolia, Clitoria mariana, Coreopsis major, Pityopsis aspera, Solidago nemoralis, Baptisia tinctoria, Chrysopsis mariana, Helianthus divaricatus, Potentilla canadensis, Hieracium venosum, Solidago pinetorum, Helianthus spp., Solidago arguta, Galium pilosum, Hypoxis hirsuta, Hexastylis minor, Desmodium rotundifolium, Desmodium nudiflorum, Houstonia longifolia, Euphorbia pubentissima, Iris verna, Silphium compositum, Euphorbia corollata, Gentiana villosa, Rhynchosia tomentosa, Goodyera pubescens, Ionactis linariifolia, Cladina spp., Cypripedium acaule, Lespedeza cuneata (I), Lespedeza bicolor (I)

Herb layer - graminoids: Schizachyrium scoparium, Danthonia spicata, Dichanthelium commutatum, Dichanthelium depauperatum, Piptochaetium avenaceum, Andropogon ternarius, Sorghastrum nutans, Carex nigromarginata, Carex albicans, Danthonia sericea, Saccharum alopecuroides, Scleria oligantha, Carex muehlenbergii

(I) = introduced

State 1

Reference State

This mature forest state is generally dominated by dry-site oaks, or a mixture of dry-site oaks and pines, with acid-tolerant flora in the understory.

Characteristics and indicators. Stands are uneven-aged with at least some old trees present.

Community 1.1

Dry Triassic Basin Upland Woodland - Fire Maintained Phase

This is an open canopy mature forest community/phase. Regular low-intensity fires have been reintroduced, keeping the understory somewhat open, increasing the cover and

diversity of herbaceous species and limiting the importance of fire-intolerant woody species.

Resilience management. This community/phase is maintained through regular prescribed burns. The recruitment of fire-adapted oaks and pines benefits from regular low-intensity ground fires, as these forests evolved under a more regular fire regime. Tree ring data suggests that the mean fire return interval of the past in the Southern Piedmont is approximately 6 years, though the actual return interval varied from 3 to 16 years. To approximate the pre-colonial fire regime, prescribed burns should be carried out every 4 to 8 years.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by dry-site oaks, or a mixture of dry-site oaks and pines. Characteristic species include post oak (Quercus stellata), white oak (Quercus alba), shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), black oak (Quercus velutina), and southern red oak (Quercus falcata). Canopy cover is lower than in the fire suppressed phase.

Forest understory. Characteristic understory tree species include blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), and flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), along with saplings of canopy species.

Common understory shrub species include deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata).

The herb layer is denser and grassier than in the fire suppressed phase.

Dominant plant species

-

post oak (Quercus stellata), tree

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

black oak (Quercus velutina), tree

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

white fringetree (Chionanthus virginicus), tree

-

deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), shrub

-

Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), shrub

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), shrub

-

St. Andrew's cross (Hypericum hypericoides ssp. multicaule), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), shrub

-

New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

Carolina rose (Rosa carolina), shrub

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), grass

-

variable panicgrass (Dichanthelium commutatum), grass

-

starved panicgrass (Dichanthelium depauperatum), grass

-

blackseed speargrass (Piptochaetium avenaceum), grass

-

splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternarius), grass

-

downy danthonia (Danthonia sericea), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

black edge sedge (Carex nigromarginata), grass

-

whitetinge sedge (Carex albicans), grass

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

lespedeza (Lespedeza), other herbaceous

-

ticktrefoil (Desmodium), other herbaceous

-

anisescented goldenrod (Solidago odora), other herbaceous

-

common dittany (Cunila origanoides), other herbaceous

-

woman's tobacco (Antennaria plantaginifolia), other herbaceous

-

queendevil (Hieracium gronovii), other herbaceous

-

Atlantic pigeonwings (Clitoria mariana), other herbaceous

-

greater tickseed (Coreopsis major), other herbaceous

-

pineland silkgrass (Pityopsis aspera), other herbaceous

Community 1.2

Dry Triassic Basin Upland Forest - Fire Suppressed Phase

This is a partially open to closed canopy mature forest community/phase. This phase accounts for the majority of contemporary examples. Canopy cover is higher than in stands in which fire has been reintroduced and the herb layer is typically sparser. The pine component can have a greater proportion of loblolly pine or Virginia pine and the understory usually contains a greater proportion of fire-intolerant species.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by dry-site oaks, or a mixture of dry-site oaks and pines. Characteristic species include post oak (Quercus stellata), white oak (Quercus alba), black oak (Quercus velutina), southern red oak (Quercus falcata), and shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata). Canopy cover is higher than in the fire maintained phase.

Forest understory. Characteristic understory tree species include blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), red maple (Acer rubrum), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), and American beech (Fagus grandifolia), along with saplings of canopy species.

Common understory shrub species include deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata). Vine cover can be higher than in the fire maintained phase.

The herb layer is sparser, less grassy, and less diverse than in the fire maintained phase.

Dominant plant species

-

post oak (Quercus stellata), tree

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

black oak (Quercus velutina), tree

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), shrub

-

Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), shrub

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

cat greenbrier (Smilax glauca), shrub

-

saw greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox), shrub

-

roundleaf greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), shrub

-

mapleleaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), shrub

-

poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), grass

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

black edge sedge (Carex nigromarginata), grass

-

whitetinge sedge (Carex albicans), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

rattlesnakeweed (Hieracium venosum), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Long-term exclusion of fire causes an increase in fire-intolerant understory species and a deterioration of the abundance and diversity of herbaceous species.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

The fire suppressed phase can be managed towards the fire maintained phase through a combination of prescribed burns and selective removals. To approximate the pre-colonial fire regime, prescribed burns should be carried out every 4 to 8 years.

Context dependence. After decades of fire suppression, most upland forests of the Southeast have undergone mesophication, or succession toward forest systems that are less apt to burn. If prescribed fire is to be used as a management tool in fire suppressed ecosystems of the Piedmont, planning will be needed in some forest systems to overcome the effects of mesophication in the early stages of fire reintroduction.

State 2

Secondary Succession State

This state develops in the immediate aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clearcut logging, or other large-scale disturbances that lead to canopy removal. Which species colonize a particular location in the wake of a disturbance does involve a considerable degree of chance. It also depends a great deal on the type, duration, and magnitude of the disturbance event.

Characteristics and indicators. Plant age distribution is even. Plants exhibit pioneering traits such as rapid growth, early reproduction, and shade-intolerance.

Community 2.1

Old-field Pine-Hardwood Forest Phase

This forested successional phase develops in the wake of recent, large-scale disturbances which have resulted in canopy removal. Stands are even-aged and species diversity is low. The canopy is usually dominated by pines, with hardwoods confined mostly to the understory. Species that exhibit pioneering traits are usually most abundant.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by pines, including loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), Virginia pine (P. virginiana), and shortleaf pine (P. echinata). Generally, Virginia pine becomes increasingly important to the north and west, while loblolly pine is favored toward the south and east.

Forest understory. Common understory tree species include sassafras (Sassafras albidum), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), red maple (Acer rubrum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua). Seedlings of dry-site oaks are usually present in the understory. These seedlings are released gradually as the forest matures and the pines begin to die off.

In the shrub layer, representative species include various blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), along with several vines.

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

dwarf cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis), other herbaceous

-

moccasin flower (Cypripedium acaule), other herbaceous

Community 2.2

Shrub-dominated Successional Phase

This successional phase is dominated by shrubs and vines, along with seedlings of opportunistic hardwoods and pines. It grades into the forested successional phase as tree seedlings become saplings and begin to occupy more of the canopy cover.

Forest overstory. Species composition varies considerably from location to location.

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

winged elm (Ulmus alata), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), tree

-

silktree (Albizia julibrissin), tree

-

princesstree (Paulownia tomentosa), tree

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), shrub

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

Indianhemp (Apocynum cannabinum), other herbaceous

Community 2.3

Herbaceous Early Successional Phase

This transient community is composed of the first herbaceous invaders in the aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clearcut logging, or other large-scale natural disturbances that lead to canopy removal.

Resilience management. If the user wishes to maintain this community/phase for wildlife or pollinator habitat, a prescribed burn, mowing, or prescribed grazing will be needed at least once annually to prevent community pathway 2.3A. To that end, as part of long-term maintenance, periodic overseeding of wildlife or pollinator seed mixtures can be helpful in ensuring the viability of certain desired species and maintaining the desired composition of species for user goals.

Dominant plant species

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternarius), grass

-

crabgrass (Digitaria), grass

-

annual fescue (Vulpia myuros), grass

-

sixweeks fescue (Vulpia octoflora), grass

-

lovegrass (Eragrostis), grass

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis), other herbaceous

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

Virginia dwarfdandelion (Krigia virginica), other herbaceous

-

dwarf cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis), other herbaceous

-

fleabane (Erigeron), other herbaceous

-

annual ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), other herbaceous

-

Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), other herbaceous

-

blackeyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), other herbaceous

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.3

The old-field pine-hardwood forest phase can return to the herbaceous early successional phase through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Context dependence. Note: if the user wishes to use this community pathway to create wildlife or pollinator habitat, please contact a local NRCS office for a species list specific to the area of interest and user needs.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

The shrub-dominated successional phase naturally moves towards the old-field pine-hardwood forest through natural succession.

Pathway 2.2B

Community 2.2 to 2.3

The shrub-dominated successional phase can return to the herbaceous early successional phase through brush management, including herbicide application, mechanical removal, prescribed grazing, or fire.

Context dependence. Note: if the user wishes to use this community pathway to create wildlife or pollinator habitat, please contact a local NRCS office for a species list specific to the area of interest and user needs.

If the user wishes to maintain the shrub-dominated successional phase long term, for wildlife habitat or other uses, periodic use of this community pathway is necessary to prevent community pathway 2.2A, which happens inevitably unless natural succession is set back through disturbance.

Pathway 2.3A

Community 2.3 to 2.2

The herbaceous early successional phase naturally moves towards the shrub-dominated successional phase through natural succession. The process takes approximately 3 years on average, barring any major disturbances capable of inhibiting natural succession.

State 3

High-graded Hardwood Forest State

This state develops as a consequence of high-grading, where the most valuable trees are removed, leaving less desirable timber specimens behind. Trees left behind include undesirable timber species, trees of poor form, diseased trees, or genetically inferior trees.

Characteristics and indicators. Typically, high-graded stands consist of a combination of residual stems from the previous stand, a high proportion of undesirable shade-tolerant species, along with some regrowth from desirable timber species. In some cases, large-diameter trees of desirable timber species may be present, but upon closer inspection, these trees usually have serious defects that resulted in their being left behind in earlier cuts.

Resilience management. Landowners with high-graded stands have two options for improving timber production: 1) rehabilitate, or 2) regenerate. To rehabilitate a stand, the landowner must evaluate existing trees to determine if rehabilitation is justified. If the proportion of high-quality specimens present in the stand is low, then the stand should be regenerated. In many cases, poor quality of the existing stand is the result of decades of mismanagement. Drastic measures are often required to get the stand back into good timber production.

State 4

Managed Pine Plantation State

This converted state is dominated by planted timber trees. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) is the most commonly planted species. Even-aged management is the most common timber management system.

Note: if the user wishes to convert stands dominated by hardwoods to planted pine, clearcutting will usually be necessary first, allowing herbaceous pioneers to establish on the site in the weeks or months prior to planting. Users should utilize measures described in transition T2B under these circumstances.

Resilience management. Hardwood Encroachment:

Hardwood encroachment can be problematic in managed pine plantations. Good site preparation, proper stocking, and periodic thinning are advisable to reduce hardwood competition.

Overstocking:

The overstocked condition commonly occurs in naturally regenerated stands. When competition from other pines begins to impact the health and productivity of the stand, precommercial thinning should be considered. At this point, the benefit of thinning usually outweighs the potential for invasion and competition from non-pine species. As the target window for thinning passes, the condition of the stand can slowly deteriorate if no action is taken. Under long-term overstocked conditions, trees are more prone to stresses, including pine bark beetle infestation and damage from wind or ice.

High-grading:

In subsequent commercial thinnings, care should be taken in tree selection. High quality specimens should be left to reach maturity, while slower growing trees or those with defects should be removed sooner. If high quality specimens are harvested first, trees left behind are often structurally unsound, diseased, genetically inferior, or of poor form. This can have long-term implications for tree genetics and for the condition of the stand (Felix III 1983; Miller et al. 1995, 2003; Megalos 2019).

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

moccasin flower (Cypripedium acaule), other herbaceous

-

dwarf cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis), other herbaceous

State 5

Pasture/Hayland State

This converted state is dominated by herbaceous forage species.

Resilience management. Overgrazing and High Foot Traffic:

In areas that are subject to high foot traffic from livestock and equipment, and/or long-term overgrazing, unpalatable weedy species tend to invade, as most desirable forage species are less competitive under these conditions. High risk areas include locations where livestock congregate for water, shade, or feed, and in travel lanes, gates, and other areas of heavy use. Plant species that are indicative of overgrazing or excessive foot traffic on this ecological site include buttercup (Ranunculus spp.), plantain (Plantago spp.), sneezeweed (Helenium amarum), cudweed (Pseudognaphalium spp.), slender yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis dillenii), Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), Virginia pepperweed (Lepidium virginicum), black medick (Medicago lupulina), Japanese clover (Kummerowia striata), annual bluegrass (Poa annua), poverty rush (Juncus tenuis), rattail fescue (Vulpia myuros), and Indian goosegrass (Eleusine indica), among others. A handful of desirable forage species are also tolerant of heavy grazing and high foot traffic, including white clover (Trifolium repens), dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), and bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon). An overabundance of these species, along with poor plant vigor and areas of bare soil, may imply that excessive foot traffic and/or overgrazing is a concern, either in the present or in the recent past.

Soil Fertility and pH Management:

Like overgrazing and excessive foot traffic, inadequate soil fertility and pH management can lead to invasion from several common weeds of pastures and hayfields. Species indicative of poor soil fertility and/or suboptimal pH on this ecological site include broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), Japanese clover (Kummerowia striata), common sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), among others. Most of these weedy invaders do not compete well in dense, rapidly growing pastures and hayfields. By maintaining soil fertility and pH, managing grazing to favor desirable forage species, and clipping behind grazing rotations when needed, forage grasses and forbs can usually outcompete weedy invaders.

Brush Encroachment:

Brush encroachment can be problematic in some pastures, particularly near fence lines where there is often a ready seed source. Pastures subject to low stocking density and long-duration grazing rotations can also be susceptible to encroachment from woody plants. Shorter grazing rotations of higher stocking density can help alleviate pressure from shrubs and vines with low palatability or thorny stems. Clipping behind grazing rotations, annual brush hogging, and multispecies grazing systems (cattle with or followed by goats) can also be helpful. Common woody invaders of pasture on this ecological site include rose (Rosa spp.), blackberry (Rubus spp.), saw greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), and black cherry (Prunus serotina).

Dominant plant species

-

dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), grass

-

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

purpletop tridens (Tridens flavus), grass

-

tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), grass

-

hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

smooth crabgrass (Digitaria ischaemum), grass

-

white clover (Trifolium repens), other herbaceous

-

Japanese clover (Kummerowia striata), other herbaceous

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

black medick (Medicago lupulina), other herbaceous

-

field clover (Trifolium campestre), other herbaceous

-

dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), other herbaceous

-

narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata), other herbaceous

State 6

Cropland State

This converted state produces food or fiber for human uses. It is dominated by domesticated crop species, along with typical weedy invaders of cropland. Soils associated with this ecological site are not well-suited to crop production. Erosion, plant water limitations, and soil fertility limitations can all be problematic on this ecological site when soils are put into crop production.

Community 6.1

Conservation-management Cropland Phase

This cropland phase is characterized by the practice of no-tillage or strip-tillage, and other soil conservation practices. Though no-till systems offer many benefits, several weedy species tend to be more problematic under this type of management system. In contrast with conventional tillage systems, problematic species in no-till systems include biennial or perennial weeds, owing to the fact that tillage is no longer used in weed management.

Community 6.2

Conventional-management Cropland Phase

This cropland phase is characterized by the recurrent use of tillage as a management tool. Due to the frequent disturbance regime, weedy invaders tend to be annual herbaceous species that reproduce quickly and are prolific seed producers.

Resilience management. The potential for soil loss is high under this management system. Measures should be put in place to limit erosion.

Pathway 6.1A

Community 6.1 to 6.2

The conservation-tillage cropland phase can shift to the conventional-tillage cropland phase through cessation of conservation tillage practices and the reintroduction of conventional tillage practices.

Context dependence. Soil and vegetation changes associated with this community pathway typically occur several years after reintroduction of conventional tillage practices. These changes continue to manifest as conventional tillage is continued, before reaching a steady state.

Pathway 6.2A

Community 6.2 to 6.1

The conventional-tillage cropland phase can be brought into the conservation-tillage cropland phase through cessation of conventional tillage and implementation of one of several conservation tillage options, including no-tillage or strip-tillage.

Context dependence. Soil and vegetation changes associated with this community pathway typically occur several years after implementation of conservation tillage. These changes continue to manifest as conservation tillage is continued, before reaching a steady state.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

The reference state can transition to the secondary succession state through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The reference state can transition to the high-graded hardwood forest state through selective removal of the most valuable trees, leaving undesirable timber specimens behind. This may occur through multiple cutting cycles over the course of decades or longer, each cut progressively worsening the condition of the stand.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 5

The reference state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T1D

State 1 to 6

The reference state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 1

The secondary succession state can transition to the reference state through long-term natural succession. This process can be accelerated to some degree by a combination of prescribed burns and selective harvesting of pines and opportunistic hardwoods.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

The secondary succession state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and planting of timber trees. Thinning alone may be sufficient for portions of the forest if pines have already established, though it is rarely sufficient for an entire forest patch.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

The secondary succession state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning wooded or semi-wooded land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T2D

State 2 to 6

The secondary succession state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) weed control, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Constraints to recovery. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking may be needed to successfully transition land that has been fallow for some time back to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the secondary succession state through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Transition T3C

State 3 to 5

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T3D

State 3 to 6

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) herbicide application, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the secondary succession state through abandonment of forestry practices (with or without timber tree harvest).

Transition T4B

State 4 to 5

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical stump and debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Applications of fertilizer and lime can be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T4C

State 4 to 6

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the cropland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical stump and debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, 5) herbicide application, 6) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the secondary succession state through long-term cessation of grazing.

Transition T5B

State 5 to 4

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and tree planting.

Transition T5C

State 5 to 6

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the cropland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) applications of fertilizer/lime, 3) weed control, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T6A

State 6 to 2

The cropland state can transition to the secondary succession state through agricultural abandonment.

Transition T6B

State 6 to 4

The cropland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and tree planting.

Transition T6C

State 6 to 5

The cropland state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) weed control, and 3) planting of perennial forage grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. To convert cropland to pasture or hayland, weed control and good seed-soil contact are important. It is also critical to review the labels of herbicides used for weed control and on the previous crop. Many herbicides have plant-back restrictions, which if not followed could carryover and kill forage seedlings as they germinate. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.