Ecological dynamics

U.S. National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) associations that are consistent with reference conditions on this ecological site include CEGL008475 Quercus alba - Quercus rubra - Carya tomentosa / Vaccinium stamineum / Desmodium nudiflorum (USNVC 2022).

MATURE FORESTS

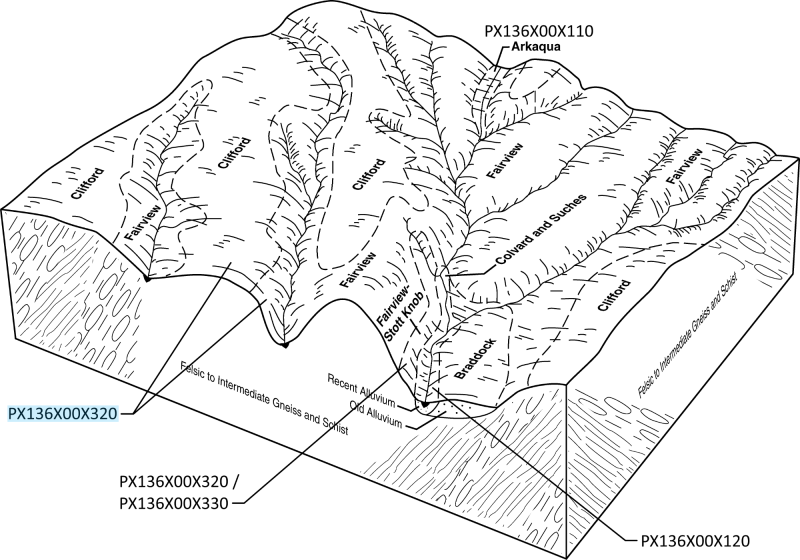

The reference state supports the typical, and historic, acidic oak-hickory forest of the Southern Piedmont. This forest type is arguably the most widespread non-ruderal forest type in the Piedmont, which before European settlement, covered large expanses of the uplands of the MLRA. Although old-growth stands are somewhat uncommon, it is still one of the most prevalent matrix forest types in the Southern Piedmont. It is a closed to somewhat open canopy forest dominated by mesophytic and dry-mesophytic oaks, with a much smaller contribution from hickories and pines, and with occasional dry-site oaks. The vegetation is distinguished from that of drier acidic ecological site concepts by the relative scarcity of dry-site oaks (e.g., Q. marilandica, Q. stellata, Q. velutina, Q. montana, Q. coccinea, Q. falcata, etc.). Several of these species may be present, but they are generally of low cover.

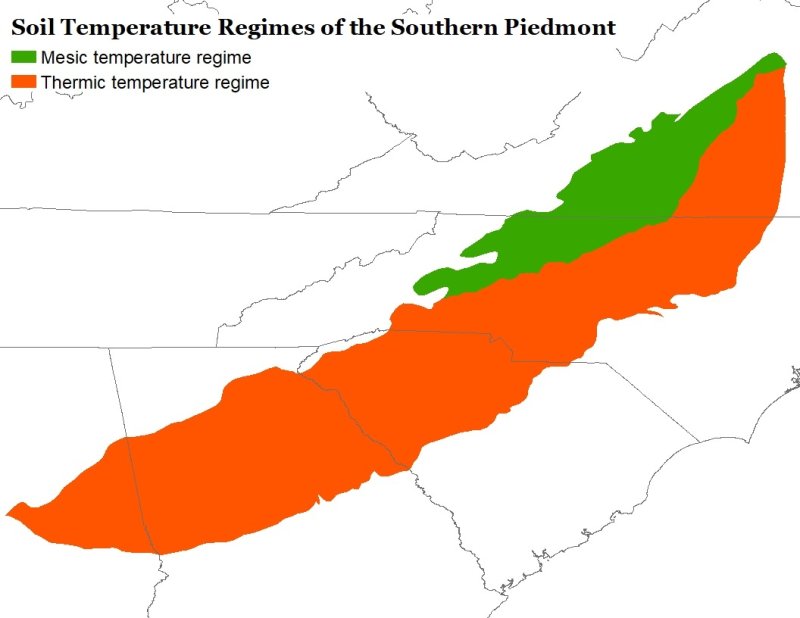

Under reference conditions, oaks are dominant in the canopy. White oak (Quercus alba) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra) are the principal species, of which white oak is usually more important. The hickory component of the canopy is of much lower cover. Most characteristic are mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa) and pignut hickory (Carya glabra). Hickories tend to be much more abundant in the understory. Somewhat moister and cooler landscape positions typically favor a higher cover of northern red oak. This species is comparatively more abundant in the mesic soil temperature regime portion of the MLRA overall.

In mature stands, pines are typically scattered throughout the forest, with Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) and shortleaf pine (P. echinata) usually being most important in the mesic soil temperature regime portion of the MLRA, though eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) can also be present. Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), though more abundant in the early stages of succession, is also characteristic of mature stands. Like the pine species, it is usually of low cover, colonizing and reproducing chiefly in canopy gaps.

In the subcanopy layer, representative species include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), red maple (Acer rubrum), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), American holly (Ilex opaca), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), and hickory (Carya spp.).

The shrub and herb layers are dominated by acid-loving flora, including those of the heath family, however the shrub and herb layers are less acidic in character than in drier and more infertile acidic uplands. Under reference conditions, the shrub layer is typically sparse, with seedlings and saplings of canopy species, or vines, occupying much of the cover.

Characteristic shrub species include deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), and bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus). Characteristic vines include muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) and Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia).

Although the herb layer is generally sparse, it can be impressively species-rich under reference conditions, especially where fire has been reintroduced. Low species richness is often the result of long-term overgrazing by large deer populations. Species richness can be increased through effective deer population management, as well as through the reintroduction of regular, low-intensity ground fires.

Typical herbaceous species include nakedflower ticktrefoil (Desmodium nudiflorum), littlebrownjug (Hexastylis arifolia), Virginia heartleaf (Hexastylis virginica), striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), crippled cranefly (Tipularia discolor), dimpled troutlily (Erythronium umbilicatum), downy rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera pubescens), and rattlesnakeweed (Hieracium venosum). Additional species representative of fire-maintained stands include devil's grandmother (Elephantopus tomentosus), hairy bedstraw (Galium pilosum), woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus), several species of lespedeza (Lespedeza spp.) and ticktrefoil (Desmodium spp.), and an array of grasses and sedges.

DYNAMICS OF NATURAL SUCCESSION AND FIRE ECOLOGY

On Piedmont uplands, the historical influence of fire on successional dynamics was likely expressed on a continuum, from dry to moist, where moist or sheltered sites were shaped more by gap-driven dynamics and dry or exposed sites more by fire. On intermediate sites, their respective influence on successional dynamics probably fell somewhere in between. While the historic fire return interval is thought to be relatively similar across most of the Southern Piedmont uplands, moister sites were less prone to fire and hence burned less completely and at lower intensities than drier sites.

Like other moist oak-hickory forests in the region, successional dynamics are thought to be primarily gap-driven, with small-scale natural disturbances such as windthrow, drought, and disease, usually affecting only small portions of the forest at a time. Canopy gaps are readily colonized by early successional herbs and shrubs, and later by pines and opportunistic hardwoods. These localized events are inconspicuous, but cumulatively they help shape the age class distribution, structure, and species composition in these forests.

In the past, regular low-intensity fires would have kept the understory somewhat more open than at present and constrained the growth of fire-intolerant woody species. Periodic severe fires would have likely occurred during unusually dry and windy conditions, presumably resulting in catastrophic tree mortality and stand replacing changes. The reduction in the frequency of fires over the past century has allowed shade-tolerant, fire-sensitive trees such as red maple (Acer rubrum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), and American holly (Ilex opaca) to become more abundant in many upland forests in the Southeast.

A combination of prescribed burns and selective removals can open up the understory and constrain the growth of fire-intolerant ruderal species, thereby restoring the health and vigor of forests that evolved under a more regular fire regime.

YOUNG SECONDARY FORESTS

On relatively undisturbed sites, stands are uneven-aged, with at least some old trees present. In areas that were cultivated in the recent past however, having been left idle for some time, even-aged pine stands dominate the landscape. These rapidly maturing pioneers are replaced by oaks and hickories only as the pines die.

In general, young secondary forests on this ecological site are dominated by Virginia pine (P. virginiana), along with opportunistic hardwoods such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), red maple (Acer rubrum), and tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera). Oaks and hickories are usually confined to the understory of young secondary stands. Their growth is temporarily suppressed by the cover of faster growing tree species.

Under a canopy of pines, a shift toward dry-site understory species is often observed. In the Southern Piedmont, old-field pine stands typically exhibit a sparse, xerophytic herb-shrub stratum, resulting from intense competition with the dominant pines, whose roots form a closed network within the upper few inches of soil. Low levels of sunlight and a thick layer of pine litter on the forest floor further suppress herb and shrub development. In such an environment, striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), blueberry (Vaccinium sp.), and various other members of the heath family are well-adapted for survival (Billings 1938; Oosting 1942; Peet and Christensen 1980; Skeen et al. 1980; Felix III et al. 1983; Schafale and Weakley 1990; Cowell 1998; Spira 2011; Fleming 2012; Guyette et al. 2012; Schafale 2012a, 2012b; Vander Yacht et al. 2020; Fleming et al. 2021; Greenberg et al. 2021; Spooner et al. 2021).

SPECIES LIST

Canopy layer: Quercus alba, Quercus rubra, Quercus falcata, Carya tomentosa, Carya glabra, Pinus echinata, Pinus virginiana, Liriodendron tulipifera, Quercus velutina, Quercus coccinea, Pinus strobus

Subcanopy layer: Cornus florida, Nyssa sylvatica, Carya spp., Acer rubrum, Diospyros virginiana, Fagus grandifolia, Oxydendrum arboreum, Ilex opaca, Prunus serotina, Liquidambar styraciflua,

Vines/lianas: Vitis rotundifolia, Smilax rotundifolia, Smilax glauca, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, Loncera japonica (I),

Shrub layer: Vaccinium stamineum, Vaccinium pallidum, Euonymus americanus, Viburnum acerifolium, Ilex opaca, Ligustrum sinense (I), Elaeagnus umbellata (I)

Herb layer - forbs: Desmodium nudiflorum, Hexastylis arifolia, Hexastylis virginica, Chimaphila maculata, Asplenium platyneuron, Tipularia discolor, Erythronium umbilicatum, Elephantopus tomentosus, Goodyera pubescens, Hieracium venosum, Helianthus divaricatus, Galium pilosum, Hypoxis hirsuta, Aristolochia serpentaria, Cypripedium acaule, Desmodium spp., Lespedeza spp., Helianthus divaricatus

Herb layer - graminoids: Dichanthelium spp., Danthonia spicata, Carex spp. (cephalophora, albicans, digitalis, hirsutella, laxiflora)

(I) = introduced

State 1

Reference State

This mature forest state is generally dominated by mesophytic and dry-mesophytic oaks, with a much smaller contribution from hickories and pines, and with occasional dry-site oaks.

Characteristics and indicators. Stands are uneven-aged with at least some old trees present.

Resilience management. Deer population management is critical to sustaining the diversity of herbaceous understory species.

Community 1.1

Moist Acidic Oak-Hickory Forest - Fire Maintained Phase

This is a closed to somewhat open canopy mature forest community/phase. Regular low-intensity fires have been reintroduced, keeping the understory somewhat open, increasing the cover and diversity of herbaceous species and limiting the importance of fire-intolerant woody species.

Resilience management. This community/phase is maintained through regular prescribed burns. The recruitment of fire-adapted oaks and pines benefits from regular low-intensity ground fires, as these forests evolved under a more regular fire regime. Tree ring data suggests that the mean fire return interval of the past in the Southern Piedmont is approximately 6 years, though the actual return interval varied from 3 to 16 years. To approximate the pre-colonial fire regime, prescribed burns should be carried out every 4 to 8 years.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by oaks. Representative species include white oak (Quercus alba) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Hickories and pines make a smaller contribution to the canopy. Representative hickory species include pignut hickory (Carya glabra) and mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa).

Forest understory. Representative understory tree species include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), and hickory (Carya spp.)

Representative understory shrub species include deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), and mapleleaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium).

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

northern red oak (Quercus rubra), tree

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

pignut hickory (Carya glabra), tree

-

mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), tree

-

deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), shrub

-

Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), shrub

-

bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), shrub

-

mapleleaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

oval-leaf sedge (Carex cephalophora), grass

-

whitetinge sedge (Carex albicans), grass

-

splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternarius), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

nakedflower ticktrefoil (Desmodium nudiflorum), other herbaceous

-

littlebrownjug (Hexastylis arifolia), other herbaceous

-

dimpled troutlily (Erythronium umbilicatum), other herbaceous

-

crippled cranefly (Tipularia discolor), other herbaceous

-

lespedeza (Lespedeza), other herbaceous

-

ticktrefoil (Desmodium), other herbaceous

-

devil's grandmother (Elephantopus tomentosus), other herbaceous

-

woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus), other herbaceous

-

hairy bedstraw (Galium pilosum), other herbaceous

-

Virginia snakeroot (Aristolochia serpentaria), other herbaceous

Community 1.2

Moist Acidic Oak-Hickory Forest - Fire Suppressed Phase

This is a closed canopy mature forest community/phase. This phase accounts for the majority of contemporary examples. Canopy cover is higher than in stands in which fire has been reintroduced. The pine component can have a greater proportion of Virginia pine and the understory usually contains a greater proportion of fire-intolerant species. The herbaceous understory is typically sparse.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by oaks. Representative species include white oak (Quercus alba) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Hickories and pines make a smaller contribution to the canopy. Representative hickory species include pignut hickory (Carya glabra) and mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa).

Forest understory. Representative understory tree species include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), and hickory (Carya spp.), along with fire-intolerant species such as American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American holly (Ilex opaca), and red maple (Acer rubrum).

Representative understory shrub species include deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), American holly (Ilex opaca), and mapleleaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium).

The herb layer is sparser and less diverse than in the fire maintained phase.

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

northern red oak (Quercus rubra), tree

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

pignut hickory (Carya glabra), tree

-

mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa), tree

-

Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tree

-

deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum), shrub

-

Blue Ridge blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), shrub

-

bursting-heart (Euonymus americanus), shrub

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

roundleaf greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), shrub

-

cat greenbrier (Smilax glauca), shrub

-

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), shrub

-

mapleleaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), shrub

-

oval-leaf sedge (Carex cephalophora), grass

-

slender woodland sedge (Carex digitalis), grass

-

nakedflower ticktrefoil (Desmodium nudiflorum), other herbaceous

-

littlebrownjug (Hexastylis arifolia), other herbaceous

-

Virginia heartleaf (Hexastylis virginica), other herbaceous

-

dimpled troutlily (Erythronium umbilicatum), other herbaceous

-

crippled cranefly (Tipularia discolor), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

downy rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera pubescens), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Long-term exclusion of fire causes an increase in fire-intolerant understory species and a deterioration of the abundance and diversity of herbaceous species.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

The fire suppressed phase can be managed towards the fire maintained phase through a combination of prescribed burns and selective removals. To approximate the pre-colonial fire regime, prescribed burns should be carried out every 4 to 8 years.

Context dependence. After decades of fire suppression, most upland hardwood forests of the Southeast have undergone mesophication, or succession toward forest systems that are less apt to burn. If prescribed fire is to be used as a management tool in fire suppressed ecosystems of the Piedmont, planning will be needed in some forest systems to overcome the effects of mesophication in the early stages of fire reintroduction.

State 2

Secondary Succession State

This state develops in the immediate aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clearcut logging, or other large-scale disturbances that lead to canopy removal. Which species colonize a particular location in the wake of a disturbance does involve a considerable degree of chance. It also depends a great deal on the type, duration, and magnitude of the disturbance event.

Characteristics and indicators. Plant age distribution is even. Plants exhibit pioneering traits such as rapid growth, early reproduction, and shade-intolerance.

Community 2.1

Old-field Pine-Hardwood Forest Phase

This forested successional phase develops in the wake of long-term agricultural abandonment or other large-scale disturbances that have led to canopy removal in the recent past. Stands are even-aged and species diversity is low. The canopy is usually dominated by pines, though opportunistic hardwoods can also be important, particularly in the early stages of tree establishment. Species that exhibit pioneering traits are usually most abundant.

Forest overstory. The overstory is typically dominated by pines. Virginia pine (P. virginiana) is the most characteristic species, though shortleaf pine (P. echinata) or eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) can also be important. Though this ecological site is outside of the native range of loblolly pine (P. taeda), escapes from nearby timber stands are becoming more common in the region.

Forest understory. Common understory tree species include red maple (Acer rubrum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), and American beech (Fagus grandifolia). Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) can also be important in young secondary stands, though its importance gradually declines to the north and west. Seedlings of oaks and hickories are usually present in the understory. These seedlings are released gradually as the forest matures and the pines begin to die off.

In the shrub layer, representative species include American holly (Ilex opaca), various blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), and several vines.

Dominant plant species

-

Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

hybrid hickory (Carya), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

roundleaf greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), shrub

-

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), shrub

-

eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), shrub

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), shrub

-

littlehead nutrush (Scleria oligantha), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

sparselobe grapefern (Botrychium biternatum), other herbaceous

-

moccasin flower (Cypripedium acaule), other herbaceous

Community 2.2

Shrub-dominated Successional Phase

This successional phase is dominated by shrubs and vines, along with seedlings of opportunistic hardwoods and pines. It typically develops beginning in the third year after agricultural abandonment or clearcut logging. It grades into the forested successional phase as tree seedlings become saplings and begin to occupy more of the canopy cover.

Forest overstory. Species composition varies considerably from location to location. Non-native species usually occupy some portion of the vine or shrub cover in most examples.

Dominant plant species

-

Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), tree

-

princesstree (Paulownia tomentosa), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

winged elm (Ulmus alata), tree

-

tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

silktree (Albizia julibrissin), tree

-

Chickasaw plum (Prunus angustifolia), tree

-

black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

grape (Vitis), shrub

-

Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), shrub

-

eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), shrub

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

Canada goldenrod (Solidago altissima), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

Indianhemp (Apocynum cannabinum), other herbaceous

Community 2.3

Herbaceous Early Successional Phase

This transient community is composed of the first herbaceous invaders in the aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clearcut logging, or other large-scale natural disturbances that lead to canopy removal.

Species composition is highly variable at this stage of succession. In addition to the named species, other herbaceous pioneers common to this ecological site include wild lettuce (Lactuca spp.), sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), vetch (Vicia spp.), dock (Rumex spp.), yellow crownbeard (Verbesina occidentalis), dwarf dandelion (Krigia virginica), Indianhemp (Apocynum cannabinum), beggarticks (Bidens spp.), slender yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis dillenii), Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota), morning-glory (Ipomoea spp.), garden cornflower (Centaurea cyanus), dwarf cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis), common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), evening primrose (Oenothera spp.), hairy cat's ear (Hypochaeris radicata), spiny sowthistle (Sonchus asper), and many others.

Resilience management. If the user wishes to maintain this community/phase for wildlife or pollinator habitat, a prescribed burn, mowing, or prescribed grazing will be needed at least once annually to prevent community pathway 2.3A. To that end, as part of long-term maintenance, periodic overseeding of wildlife or pollinator seed mixtures can be helpful in ensuring the viability of certain desired species and maintaining the desired composition of species for user goals.

Dominant plant species

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), grass

-

smooth crabgrass (Digitaria ischaemum), grass

-

southern crabgrass (Digitaria ciliaris), grass

-

Japanese bristlegrass (Setaria faberi), grass

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

annual bluegrass (Poa annua), grass

-

American burnweed (Erechtites hieraciifolius), other herbaceous

-

American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), other herbaceous

-

Canada goldenrod (Solidago altissima), other herbaceous

-

Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis), other herbaceous

-

annual ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), other herbaceous

-

fleabane (Erigeron), other herbaceous

-

cudweed (Pseudognaphalium), other herbaceous

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.3

The old-field pine-hardwood forest phase can return to the herbaceous early successional phase through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Context dependence. Note: if the user wishes to use this community pathway to create wildlife or pollinator habitat, please contact a local NRCS office for a species list specific to the area of interest and user needs.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

The shrub-dominated successional phase naturally moves towards the old-field pine-hardwood forest through natural succession.

Pathway 2.2B

Community 2.2 to 2.3

The shrub-dominated successional phase can return to the herbaceous early successional phase through brush management, including herbicide application, mechanical removal, prescribed grazing, or fire.

Context dependence. Note: if the user wishes to use this community pathway to create wildlife or pollinator habitat, please contact a local NRCS office for a species list specific to the area of interest and user needs.

If the user wishes to maintain the shrub-dominated successional phase long term, for wildlife habitat or other uses, periodic use of this community pathway is necessary to prevent community pathway 2.2A, which happens inevitably unless natural succession is set back through disturbance.

Pathway 2.3A

Community 2.3 to 2.2

The herbaceous early successional phase naturally moves towards the shrub-dominated successional phase through natural succession. The process takes approximately 3 years on average, barring any major disturbances capable of inhibiting natural succession.

State 3

High-graded Hardwood Forest State

This state develops as a consequence of high-grading, where the most valuable trees are removed, leaving less desirable timber specimens behind. Trees left behind include undesirable timber species, trees of poor form, diseased trees, or genetically inferior trees.

Characteristics and indicators. Typically, high-graded stands consist of a combination of residual stems from the previous stand, a high proportion of undesirable shade-tolerant species, along with some regrowth from desirable timber species. In some cases, large-diameter trees of desirable timber species may be present, but upon closer inspection, these trees usually have serious defects that resulted in their being left behind in earlier cuts.

Resilience management. Landowners with high-graded stands have two options for improving timber production: 1) rehabilitate, or 2) regenerate. To rehabilitate a stand, the landowner must evaluate existing trees to determine if rehabilitation is justified. If the proportion of high-quality specimens present in the stand is low, then the stand should be regenerated. In many cases, poor quality of the existing stand is the result of decades of mismanagement. Drastic measures are often required to get the stand back into good timber production.

State 4

Managed Pine Plantation State

This converted state is dominated by planted timber trees. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) is the most commonly planted species, though Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) and eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) can also be successfully managed for timber in this part of the MLRA. Even-aged management is the most common timber management system.

Note: if the user wishes to convert stands dominated by hardwoods to planted pine, clearcutting will usually be necessary first, allowing herbaceous pioneers to establish on the site in the weeks or months prior to planting. Users should utilize measures described in transition T2B under these circumstances.

Resilience management. Hardwood Encroachment:

Hardwood encroachment can be problematic in managed pine plantations. Good site preparation, proper stocking, and periodic thinning are advisable to reduce hardwood competition.

Overstocking:

The overstocked condition commonly occurs in naturally regenerated stands. When competition from other pines begins to impact the health and productivity of the stand, precommercial thinning should be considered. At this point, the benefit of thinning usually outweighs the potential for invasion and competition from non-pine species. As the target window for thinning passes, the condition of the stand can slowly deteriorate if no action is taken. Under long-term overstocked conditions, trees are more prone to stresses, including pine bark beetle infestation and damage from wind or ice.

High-grading:

In subsequent commercial thinnings, care should be taken in tree selection. High quality specimens should be left to reach maturity, while slower growing trees or those with defects should be removed sooner. If high quality specimens are harvested first, trees left behind are often structurally unsound, diseased, genetically inferior, or of poor form. This can have long-term implications for tree genetics and for the condition of the stand (Felix III 1983; Miller et al. 1995, 2003; Megalos 2019).

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

red maple (Acer rubrum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

hybrid hickory (Carya), tree

-

American holly (Ilex opaca), shrub

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

grape (Vitis), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

littlehead nutrush (Scleria oligantha), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), other herbaceous

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

moccasin flower (Cypripedium acaule), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

State 5

Pasture/Hayland State

This converted state is dominated by herbaceous forage species.

Resilience management. Overgrazing and High Foot Traffic:

In areas that are subject to high foot traffic from livestock and equipment, and/or long-term overgrazing, unpalatable weedy species tend to invade, as most desirable forage species are less competitive under these conditions. High risk areas include locations where livestock congregate for water, shade, or feed, and in travel lanes, gates, and other areas of heavy use. Plant species that are indicative of overgrazing or excessive foot traffic on this ecological site include buttercup (Ranunculus spp.), plantain (Plantago spp.), curly dock (Rumex crispus), sneezeweed (Helenium amarum), cudweed (Pseudognaphalium spp.), slender yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis dillenii), Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), Virginia pepperweed (Lepidium virginicum), black medick (Medicago lupulina), Japanese clover (Kummerowia striata), annual bluegrass (Poa annua), poverty rush (Juncus tenuis), rattail fescue (Vulpia myuros), and Indian goosegrass (Eleusine indica), among others. A handful of desirable forage species are also tolerant of heavy grazing and high foot traffic, including white clover (Trifolium repens), dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), and bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon). An overabundance of these species, along with poor plant vigor and areas of bare soil, may imply that excessive foot traffic and/or overgrazing is a concern, either in the present or in the recent past.

Soil Fertility and pH Management:

Like overgrazing and excessive foot traffic, inadequate soil fertility and pH management can lead to invasion from several common weeds of pastures and hayfields. Species indicative of poor soil fertility and/or suboptimal pH on this ecological site include broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), sweet vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), Japanese clover (Kummerowia striata), common sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense), among others. Most of these weedy invaders do not compete well in dense, rapidly growing pastures and hayfields. By maintaining soil fertility and pH, managing grazing to favor desirable forage species, and clipping behind grazing rotations when needed, forage grasses and forbs can usually outcompete weedy invaders.

Brush Encroachment:

Brush encroachment can be problematic in some pastures, particularly near fence lines where there is often a ready seed source. Pastures subject to low stocking density and long-duration grazing rotations can also be susceptible to encroachment from woody plants. Shorter grazing rotations of higher stocking density can help alleviate pressure from shrubs and vines with low palatability or thorny stems. Clipping behind grazing rotations, annual brush hogging, and multispecies grazing systems (cattle with or followed by goats) can also be helpful. Common woody invaders of pasture on this ecological site include rose (Rosa spp.), blackberry (Rubus spp.), saw greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), black cherry (Prunus serotina), and Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense).

Dominant plant species

-

tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), grass

-

dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), grass

-

orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata), grass

-

perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), grass

-

purpletop tridens (Tridens flavus), grass

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), grass

-

sweet vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

white clover (Trifolium repens), other herbaceous

-

red clover (Trifolium pratense), other herbaceous

-

vetch (Vicia), other herbaceous

-

narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata), other herbaceous

-

black medick (Medicago lupulina), other herbaceous

-

field clover (Trifolium campestre), other herbaceous

-

common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), other herbaceous

-

wild garlic (Allium vineale), other herbaceous

-

chicory (Cichorium intybus), other herbaceous

-

dogfennel (Eupatorium capillifolium), other herbaceous

State 6

Cropland State

This converted state produces food or fiber for human uses. It is dominated by domesticated crop species, along with typical weedy invaders of cropland.

Community 6.1

Conservation-management Cropland Phase

This cropland phase is characterized by the practice of no-tillage or strip-tillage, and other soil conservation practices. Though no-till systems offer many benefits, several weedy species tend to be more problematic under this type of management system. In contrast with conventional tillage systems, problematic species in no-till systems include biennial or perennial weeds, owing to the fact that tillage is no longer used in weed management.

Community 6.2

Conventional-management Cropland Phase

This cropland phase is characterized by the recurrent use of tillage as a management tool. Due to the frequent disturbance regime, weedy invaders tend to be annual herbaceous species that reproduce quickly and are prolific seed producers.

Resilience management. The potential for soil loss is high under this management system. Measures should be put in place to limit erosion.

Pathway 6.1A

Community 6.1 to 6.2

The conservation-management cropland phase can shift to the conventional-management cropland phase through cessation of conservation tillage practices and the reintroduction of conventional tillage practices.

Context dependence. Soil and vegetation changes associated with this community pathway typically occur several years after reintroduction of conventional tillage practices. These changes continue to manifest as conventional tillage is continued, before reaching a steady state.

Pathway 6.2A

Community 6.2 to 6.1

The conventional-management cropland phase can be brought into the conservation-management cropland phase through the implementation of one of several conservation tillage options, including no-tillage or strip-tillage, along with implementation of other soil conservation practices.

Context dependence. Soil and vegetation changes associated with this community pathway typically occur several years after implementation of conservation tillage. These changes continue to manifest as conservation tillage is continued, before reaching a steady state.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

The reference state can transition to the secondary succession state through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The reference state can transition to the high-graded hardwood forest state through selective removal of the most valuable trees, leaving undesirable timber specimens behind. This may occur through multiple cutting cycles over the course of decades or longer, each cut progressively worsening the condition of the stand.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 5

The reference state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T1D

State 1 to 6

The reference state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 1

The secondary succession state can transition to the reference state through long-term natural succession. This process can be accelerated to some degree by a combination of prescribed burns and selective harvesting of pines and opportunistic hardwoods.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

The secondary succession state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and planting of timber trees. Thinning alone may be sufficient for portions of the forest if pines have already established, though it is rarely sufficient for an entire forest patch.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

The secondary succession state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning wooded or semi-wooded land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T2D

State 2 to 6

The secondary succession state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) weed control, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking may be needed to successfully transition land that has been fallow for some time back to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the secondary succession state through clearcut logging or other large-scale disturbances that cause canopy removal.

Transition T3C

State 3 to 5

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T3D

State 3 to 6

The high-graded hardwood forest state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) herbicide application, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the secondary succession state through abandonment of forestry practices (with or without timber tree harvest).

Transition T4B

State 4 to 5

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical stump and debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Applications of fertilizer and lime can be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T4C

State 4 to 6

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the cropland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical stump and debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, 5) herbicide application, 6) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the secondary succession state through long-term cessation of grazing.

Transition T5B

State 5 to 4

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and tree planting.

Transition T5C

State 5 to 6

The pasture/hayland state can transition to the cropland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) applications of fertilizer/lime, 3) herbicide application, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T6A

State 6 to 2

The cropland state can transition to the secondary succession state through agricultural abandonment.

Transition T6B

State 6 to 4

The cropland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation and tree planting.

Transition T6C

State 6 to 5

The cropland state can transition to the pasture/hayland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) weed control, and 3) planting of perennial forage grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. To convert cropland to pasture or hayland, weed control and good seed-soil contact are important. It is also critical to review the labels of herbicides used for weed control and on the previous crop. Many herbicides have plant-back restrictions, which if not followed could carryover and kill forage seedlings as they germinate. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.