Ecological dynamics

U.S. National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) associations that are consistent with reference conditions on this ecological site include CEGL003578 Pinus palustris / Quercus incana / Aristida stricta - Sorghastrum nutans - Anthaenantia villosa, and CEGL003570 Pinus palustris / Aristida stricta - Sorghastrum nutans - Anthaenantia villosa, with the former reresenting slightly drier and less fertile edaphic conditions and the latter representing conditions of slightly higher productivity (USNVC 2023).

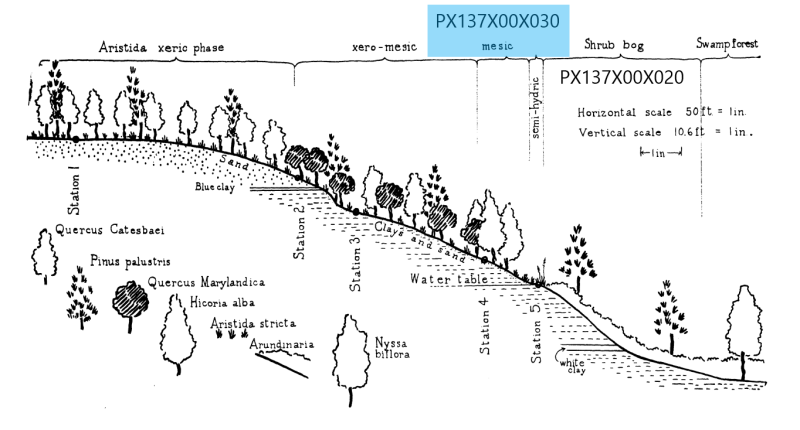

Woodland communities associated with this ecological site are similar to other longleaf pine dominated savannas of the Atlantic Coastal Plain Fall-Line Sandhills Longleaf Pine ecosystem (CES203.254), though they are significantly more mesophytic in character. Species diversity is high, particularly in the herb layer, where a diverse mixture of grasses, composites, and leguminous forbs are frequently observed. Legume diversity can be especially notable, so much so that the term "bean dip" or "pea swale" have been used occasionally to describe the flora. These longleaf pine savannas differ from other longleaf communities in that they occur on moderately well drained slopes, with relatively fertile, fine-textured, usually loamy soil. With species counts ranging between 100 and 140 vascular plant species per 1000 meters squared, these communities are extraordinarily diverse (Peet and Allard 1993).

The reference state typically supports an open to partially open woodland dominated by longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), with scrub oak cover generally increasing in the understory as plant water relations become less favorable. Scrub oaks common to the understory include bluejack oak (Quercus incana), blackjack oak (Q. marilandica), and sand post oak (Q. margaretta). Turkey oak (Quercus laevis) is generally scarce or absent. More than most other longleaf pine communities, loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) or shortleaf pine (P. echinata) may be present in the canopy, but these species are usually of minor importance with frequent fire.

Under the natural fire regime, grasses dominate the herb layer. Common species include threeawn (Aristida stricta or A. beyrichiana), which is usually dominant, together with Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), green silkyscale (Anthaenantia villosa), and various bluestems (Andropogon spp.) and rosette grasses (Dichanthelium spp.). Important forbs include aniscented goldenrod (Solidago odora), brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), and numerous legumes. With inadequate fire, brackenfern can increase in abundance, and it can even come to dominate the herb layer in the long absence of fire.

Threeawn, or wiregrass as it is commonly known, is most characteristic of frequently burned stands, with pineland threeawn (Aristida stricta) being restricted to the northern part of the MLRA and Beyrich threeawn (Aristida beyrichiana) to the southern part. In the wiregrass gap region of South Carolina, little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) generally dominates in place of threeawn.

FIRE ECOLOGY

Fire is perhaps the most critical environmental factor contributing to the development and maintenance of longleaf pine-dominated ecosystems. When frequently burned, the herb layer is dense and diverse, and the understory is open. As a consequence of fire suppression, longleaf pine ecosystems are vulnerable to succession toward forest systems that are less apt to burn, eventually supporting species that are more competitive in the absence of fire.

With inadequate fire, the understory is quickly invaded by sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) and other opportunistic hardwoods, along with shrubs. In addition, forest oaks (Quercus falcata, Q. stellata, Q. nigra), which are often present as sprouts in fire-maintained stands, may eventually reach the canopy and compete with pines. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) or shortleaf pine (P. echinata) often increase in abundance with long-term fire suppression (Barry 1980; Wharton et al. 1982; Nelson 1986; Schafale and Weakley 1990; Peet and Allard 1993; James et al. 2000; Peet 2007; Schafale 2012a, 2012b; Edwards et al. 2013).

SPECIES LIST

Canopy layer: Pinus palustris, Pinus taeda, Pinus echinata

Subcanopy layer: Quercus incana, Quercus marilandica, Quercus margaretta, Diospyros virginiana, Sassafras albidum, Nyssa sylvatica, Cornus florida, Prunus serotina, Oxydendrum arboreum, Carya tomentosa, Carya pallida, Quercus stellata, Quercus falcata, Quercus nigra, Quercus hemisphaerica

Shrub layer: Vaccinium tenellum, Gaylussacia dumosa, Vaccinium arboreum, Rhus copallinum, Toxicodendron pubescens, Hypericum hypericoides, Hypericum crux-andreae, Ceanothus americanus, Gaylussacia frondosa, Rubus arguta, Rubus cuneifolius, Yucca filamentosa, Smilax glauca, Ilex glabra, Vaccinium stamineum, Rhus michauxii, Lyonia mariana, Lyonia ligustrina, Leiophyllum buxifolium, Vitis rotundifolia, Aronia arbutifolia, Morella cerifera var. pumila, Clethra alnifolia, Symplocos tinctoria

Herb layer - forbs: Tephrosia spp. (virginiana, florida, spicata, hispidula), Lespedeza spp. (capitata, hirta, angustifolia, virginica, repens, procumbens, stuevei), Solidago odora, Pteridium aquilinum, Iris verna, Ionactis linariifolius, Symphyotrichum spp. (walteri, dumosum, concolor), Desmodium spp. (lineatum, strictum, ciliare, nuttallii, paniculatum, laevigatum, marilandicum, obtusum, floridanum), Rhynchosia reniformis, Rhynchosia tomentosa, Baptisia cinerea, Baptisia tinctoria, Stylosanthes biflora, Carphephorus bellidifolius, Euphorbia spp. (curtisii, exserta, corollata, ipecacuanhae), Pityopsis graminifolia, Pityopsis aspera var. adenolepis, Cirsium repandum, Orbexilum pedunculatum var. psoralioides, Clitoria mariana, Liatris spp. (pilosa, cokeri), Chamaecrista fasciculata, Chamaecrista nictitans, Coreopsis major, Coreopsis verticillata, Eupatorium spp. (rotundifolium, album, pilosum, compositifolium, mohrii, leucolepis, glaucescens), Galium pilosum, Chrysopsis mariana, Silphium compositum, Vernonia angustifolia, Vernonia acaulis, Sericocarpus spp. (linifolius, tortifolius, asteroides), Galactia spp. (erecta, regularis, mollis, volubilis), Viola pedata, Helianthus divaricatus, Hieracium marianum, Parthenium integrifolium, Phlox nivalis, Hypoxis hirsuta, Hypoxis wrightii, Ageratina aromatica, Tragia urens, Lechea minor, Lobelia nuttallii, Potentilla canadensis, Oenothera fruticosa, Krigia virginica, Euthamia caroliniana, Bidens aristosa, Centrosema virginianum, Gentiana autumnalis, Ruellia caroliniensis ssp. ciliosa, Amorpha herbacea var. herbacea, Penstemon australis, Ambrosia psilostachya, Solidago nemoralis, Hieracium gronovii, Chrysopsis gossypina, Physalis spp. (heterophylla, lanceolata, virginiana), Prenanthes autumnalis, Orbexilum lupinellum, Crotalaria purshii, Crotolaria rotundifolia, Angelica venenosa, Nuttallanthus canadensis, Aletris farinosa, Phaseolus polystachios var. sinuatus, Chimaphila maculata, Epigaea repens, Carphephorus odoratissimus, Callisia graminea, Sphenopholis filiformis, Pediomelum canescens, Gamochaeta purpurea, Rhexia alifanus, Pycnanthemum flexuosum, Viola villosa, Mimosa microphylla, Brickellia eupatorioides, Stylisma patens, Rhexia mariana, Sisyrinchium spp. (angustifolium, capillare), Lupinus diffusus, Seymeria cassioides, Schwalbea americana, Stillingia sylvatica, Onosmodium virginianum, Asclepias amplexifolius, Asclepias tuberosa, Erigeron vernus, Xyris caroliniana, Stylodon carneus, Dalea pinnata, Cnidoscolus urens var. stimulosus, Astragalus michauxii, Cuthbertia graminea, Polygala lutea, Polygala grandiflora, Pterocaulon pycnostachyum, Pediomelum canescens,

Herb layer - graminoids: Aristida spp. (stricta, beyrichiana), Sorghastrum nutans, Panicum virgatum, Andropogon spp. (ternarius, gyrans, virginicus, gerardii), Anthaenantia villosa, Schizachyrium scoparium, Dichanthelium spp. (aciculare, dichotomum var. tenue, strigosum, ovale, commutatum, oligosanthes, sphaerocarpon, villosissimum), Muhlenbergia capillaris, Gymnopogon brevifolius, Paspalum bifidum, Chasmanthium laxum, Danthonia sericea, Saccharum alopecuroides, Sorghastrum elliottii, Scleria spp. (ciliata, nitida, pauciflora, triglomerata), Aristida lanosa, Rhynchospora spp. (plumosa, grayi, fascicularis, torreyana), Sporobolus clandestinus, Sporobolus junceus, Tridens carolinianus, Gymnopogon ambiguus, Eragrostis spectabilis, Axonopus fissifolius, Panicum tenerum, Eragrostis curvula (ex.)

ex. = exotic

State 1

Reference State - Moist Longleaf Pine Woodland

This is the historic climax plant community for this ecological site. The canopy is open and dominated by longleaf pine, with minimal to moderate scrub oak cover in the understory. Common oaks include bluejack oak (Quercus incana), blackjack oak (Q. marilandica), and sand post oak (Q. margaretta). In contrast with drier longleaf pine-dominated uplands of the MLRA, turkey oak (Quercus laevis) is scarce or absent in the understory. Forest oaks (Quercus falcata, Q. stellata, Q. nigra, etc.) are absent in the canopy but can exist as sprouts or small trees. The herb layer is grassy and diverse. Stands are uneven-aged.

Resilience management. Warm season burns are preferable for the maintenance of longleaf pine woodlands. Dormant season fires will top-kill undesirable hardwoods, such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) and water oak (Quercus nigra), but they will quickly resprout during the following growing season (Bradley et al. 2018).

Community 1.1

Moist Longleaf Pine - Wiregrass Woodland

This community phase is dominated by widely-spaced mature longleaf pine, with a dense, grassy groundcover, and minimal understory cover from scrub oaks and other woody species. Typical canopy cover ranges from 5 to 40 percent, with a representative cover of 20 percent. Stands are uneven-aged.

Resilience management. Frequent low-intensity fire is necessary for the maintenance of this community phase. A fire return interval of 2 to 3 years is appropriate for maintenance. Grass-dominated groundcover provides necessary fine fuels for the spread of surface fires. Successful germination of longleaf pine seed is facilitated by direct sunlight and contact with bare mineral soil. These conditions are found only in the immediate aftermath of fire.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), with minimal contribution from forest oaks (Quercus falcata, Q. stellata, Q. nigra, etc.) or other pine species (Pinus taeda, P. echinata).

Forest understory. Woody understory cover is generally sparse and dominated by scrub oaks, including bluejack oak (Quercus incana), blackjack oak (Q. marilandica), and sand post oak (Q. margaretta), among others. Other common species include common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), and blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica). The shrub layer is sparse.

The herb layer is dominated by grasses, along with various composites and a diverse suite of leguminous forbs. Threeawn, or wiregrass as it is commonly known, is most characteristic of frequently burned stands, with pineland threeawn (Aristida stricta) being restricted to the northern part of the MLRA and Beyrich threeawn (Aristida beyrichiana) to the southern part. In the wiregrass gap region of South Carolina, little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) generally dominates in place of threeawn. Other common species include Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), green silkyscale (Anthaenantia villosa), and various bluestems (Andropogon spp.) and rosette grasses (Dichanthelium spp.). Species diversity is exceptionally high.

Dominant plant species

-

longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), tree

-

bluejack oak (Quercus incana), tree

-

blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), tree

-

sand post oak (Quercus margaretta), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

Atlantic poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens), shrub

-

threeawn (Aristida), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

green silkyscale (Anthaenantia villosa), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

hairawn muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris), grass

-

shortleaf skeletongrass (Gymnopogon brevifolius), grass

-

pitchfork crowngrass (Paspalum bifidum), grass

-

hoarypea (Tephrosia), other herbaceous

-

lespedeza (Lespedeza), other herbaceous

-

anisescented goldenrod (Solidago odora), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

dwarf violet iris (Iris verna), other herbaceous

-

flaxleaf whitetop aster (Ionactis linariifolius), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

ticktrefoil (Desmodium), other herbaceous

-

snoutbean (Rhynchosia), other herbaceous

-

wild indigo (Baptisia), other herbaceous

-

sidebeak pencilflower (Stylosanthes biflora), other herbaceous

Community 1.2

Mature longleaf pine overstory, mid- and understory oak encroachment, in need of fire

This community phase develops as a result of lower fire frequency. A longer fire return interval allows an increase of woody growth in the mid- and understory. Like community phase 1.1, this phase is also dominated by widely-spaced, mature longleaf pine, of similar species composition. Canopy cover typically ranges from 5 to 60 percent, with a representative cover of 30 percent. Stands are uneven-aged.

Although species composition is similar to community phase 1.1, herb cover tends to be slightly lower and less grassy. Changes to the fire regime result in some degree of hardwood encroachment, leaf litter accumulation, and a subsequent shift in the abundance of herbaceous species.

Resilience management. Relatively frequent low-intensity fire is necessary for the maintenance of this community phase. Generally, this phase begins to develop 3 to 5 years after the most recent groundfire, and is readily returned to community phase 1.1 with fire. On average, stem diameter from encroaching hardwoods is generally less than 1 inch.

If the lower fire frequency is continued long term, this community phase can be maintained with only slight increases in canopy cover. Eventually however, leaf litter accumulation inhibits the regeneration of longleaf pine. If fire suppression continues unabated, forest oaks and other hardwoods gain a foothold, eventually outcompeting any young longleaf that have established, leading to states 2, 3, and ultimately state 4. While the fire return interval is frequent enough to maintain a grass-dominated herb layer, the overall abundance and diversity of the herbaceous understory is inhibited.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), with minimal contribution from forest oaks (Quercus falcata, Q. stellata, Q. nigra, etc.) or other hardwoods. Though other pine species may be present, including loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) and shortleaf pine (P. echinata), these species are rarely abundant in the canopy.

Forest understory. Woody understory cover is generally moderately dense and dominated by scrub oaks, including bluejack oak (Quercus incana), blackjack oak (Q. marilandica), and sand post oak (Q. margaretta), among others. Other common species include common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), and black cherry (Prunus serotina). The shrub layer is generally denser than in community phase 1.1.

The herb layer is dominated by grasses, along with various composites and a diverse suite of leguminous forbs. Common species include threeawn (Aristida stricta or A. beyrichiana), which is usually dominant, together with Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), green silkyscale (Anthaenantia villosa), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and various other bluestems (Andropogon spp.) and rosette grasses (Dichanthelium spp.). Species diversity is generally lower than in community phase 1.1.

Dominant plant species

-

longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), tree

-

bluejack oak (Quercus incana), tree

-

blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), tree

-

sand post oak (Quercus margaretta), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

Atlantic poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), shrub

-

threeawn (Aristida), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

green silkyscale (Anthaenantia villosa), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

hairawn muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris), grass

-

shortleaf skeletongrass (Gymnopogon brevifolius), grass

-

pitchfork crowngrass (Paspalum bifidum), grass

-

anisescented goldenrod (Solidago odora), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

dwarf violet iris (Iris verna), other herbaceous

-

hoarypea (Tephrosia), other herbaceous

-

lespedeza (Lespedeza), other herbaceous

-

flaxleaf whitetop aster (Ionactis linariifolius), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

ticktrefoil (Desmodium), other herbaceous

-

snoutbean (Rhynchosia), other herbaceous

-

wild indigo (Baptisia), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

This community pathway occurs regularly, whenever a low-intensity fire is successfully run through the stand. It can also develop when the fire return interval is decreased from approximately 3 - 5 years to 2 - 3 years, leading to higher efficacy in controlling encroaching hardwoods and shrubs and maintaining dense groundcover. The high frequency fire regime mimics the conditions in which longleaf pine evolved.

Context dependence. Warm season burns are preferred over dormant season burns for controlling hardwood encroachment.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This community pathway occurs regularly with time in the interval between fires. It can also develop when the fire return interval is increased from approximately 2 - 3 years to 3 - 5 years to leading to higher overall cover in the understory.

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

| Native Plant Community Restoration and Management |

|

State 2

Planted Longleaf Pine Woodland with Native Ground Cover

In this state, longleaf pine is planted in an attempt to restore the system to the historic forest cover, while also allowing for the harvest of pine straw and other forest products. However, the richness of herbaceous species and associated animals rarely compare to the reference state. Still, this state is a functioning ecosystem with strong similarities to the reference plant community. With time, planted longleaf pine woodlands can become more diverse, eventually approaching conditions found in the reference state.

Planted pines are generally even-aged and evenly spaced. If the planting density is too high, the trees will eventually shade out the native ground cover needed to carry fire. Needle-fall tends to be high in overstocked stands as well, which can contribute to hotter fires when they do occur, potentially burning into the root system of some trees. Consultation with a professional forester is recommended before establishing a longleaf pine stand.

Grasses commonly planted in the understory include threeawn (Aristida stricta in the north, A. beyrichiana in the south), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). When managed appropriately, this state can be utilized as wildlife habitat or for livestock grazing.

Resilience management. Warm season burns are preferable for successful establishment of the native threeawn-dominated understory and control of woody undergrowth. Dormant season fires will top-kill undesirable hardwoods, such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) and water oak (Quercus nigra), but they will quickly resprout during the following growing season.

Site preparation needs for planting longleaf pine will vary depending on the previous land use and ecological state. For example, on former cropland or pasture, scalping and ripping/subsoiling are often necessary when preparing a site for tree planting.

When establishing longleaf pine, landowners are often faced with two options: 1) rehabilitate an existing stand, or 2) remove and regenerate with young trees. To rehabilitate a longleaf pine stand, the landowner must evaluate existing longleaf cover to determine if rehabilitation is justified. If the proportion of longleaf present in the stand is low, then the stand will likely need to be regenerated. While regeneration generally involves clear cutting and replanting, rehabilitation usually relies on natural regeneration from mature trees or a combination of natural regeneration and replanting. Rehabilitation requires selective thinning of undesirable hardwoods and pines, together with chemical or mechanical control of woody sprouts, planting of native ground cover, and fire management (Brockway et al. 2005; Bradley et al. 2018).

Dominant plant species

-

longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

threeawn (Aristida), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), grass

-

lespedeza (Lespedeza), other herbaceous

-

ticktrefoil (Desmodium), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

State 3

Degraded Longleaf Pine - Oak Woodland

The Degraded Longleaf Pine-Oak Woodland state is characterized by increased canopy closure relative to the reference state. Leaf litter accumulation inhibits the regeneration of longleaf pine and impedes the development of the herb layer. Competition from woody understory plants begins to have a negative effect on longleaf pine regeneration. Generally, this phase begins to develop 5 years or more after the most recent groundfire. On average, stem diameter from encroaching hardwoods range from approximately 1 to 4 inches. Canopy cover typically ranges from 10 to 80 percent, with a representative cover of 40 percent. Woodlands that have transitioned to this state can be either even-aged or uneven-aged, depending on whether or not the stand arose from a recent planting.

With inadequate fire, the understory is quickly invaded by sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), and other opportunistic hardwoods, along with scrub oaks (Quercus incana, Q. margaretta, Q. marilandica), and various shrubs. Forest oaks (Quercus falcata, Q. stellata, Q. nigra, etc.) begin to grow up in the understory, with water oak (Quercus nigra) becoming particularly abundant in the understory in fire-suppressed stands. Generally, the woody undergrowth does not yet compete directly with mature longleaf pine for sunlight, but woody plants do compete heavily with juvenile longleaf where it manages to establish. Pines that are intolerant of frequent fire also begin to establish, namely loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), which can reproduce profusely in the absence of fire.

Herbaceous species richness and productivity will continue to deteriorate with canopy closure. In addition, grass and legume cover begins to deteriorate, while cover from shade-tolerant, litter-tolerant forbs, such as brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), generally increases.

Resilience management. As hardwood cover continues to expand, increased shade negatively impacts native groundcover, by way of reduced cover from grasses, which in turn reduces the availability of fine fuels needed to carry a prescribed burn. This cycle results in continued succession toward hardwood dominance. Generally, this phase begins to develop 5 years or more after the most recent groundfire. Fire alone is not usually enough to transition this state back to the reference state. Restoration will usually require selective removal of undesirable hardwoods, along with the reintroduction of fire.

Warm season burns are preferable for longleaf pine restoration and maintenance. Dormant season fires will top-kill undesirable hardwoods, such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) and water oak (Quercus nigra), but they will quickly resprout during the following growing season (Bradley et al. 2018).

Dominant plant species

-

longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), tree

-

bluejack oak (Quercus incana), tree

-

sand post oak (Quercus margaretta), tree

-

blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), tree

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

post oak (Quercus stellata), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

cat greenbrier (Smilax glauca), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

slender woodoats (Chasmanthium laxum), grass

-

downy danthonia (Danthonia sericea), grass

-

threeawn (Aristida), grass

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

dwarf violet iris (Iris verna), other herbaceous

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), other herbaceous

-

ticktrefoil (Desmodium), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

anisescented goldenrod (Solidago odora), other herbaceous

State 4

Mixed Pine-Hardwood Forest

The Mixed Pine-Hardwood Forest state is characterized by the low proportion or near absence of longleaf pine in the stand. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) typically becomes the dominant canopy species in its place. Longleaf can still be present, but regeneration is not occurring. Canopy closure approaches 100 percent in many examples and a thick layer of leaf litter has accumulated on the forest floor. The loss of longleaf pine from the site is due to the lack of a favorable environment for longleaf pine regeneration, competition from other woody plants, and a significant decrease in sunlight penetration.

The canopy is dominated by pines (Pinus taeda, P. echinata, P. palustris) and forest oaks (Quercus falcata, Q. stellata, Q. nigra, etc.), with some hickory (Carya tomentosa, C. pallida), and various other hardwoods. Because of the lack of sunlight penetration to the understory, cover from shrubs is reduced relative to state 3. Herbaceous species characteristic of the reference state are usually sparse or no longer present.

Resilience management. Fire alone is not usually enough to transition this state back to the reference state. Restoration will usually require removal of undesirable pines and hardwoods, planting of longleaf pine, together with the reintroduction of fire.

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

post oak (Quercus stellata), tree

-

water oak (Quercus nigra), tree

-

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa), tree

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

dwarf violet iris (Iris verna), other herbaceous

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), other herbaceous

-

anisescented goldenrod (Solidago odora), other herbaceous

State 5

Mixed Hardwood Forest

The Mixed Hardwood Forest state is the product of long-term fire exclusion, whereby the pine-dominated forests of state 3 eventually succeed toward hardwood-dominated forests in the absence of fire. In the shade of pines, the growth of hardwood seedlings and saplings is temporarily suppressed. With the gradual transition of the stand from state 3 to state 4, juvenile oaks, hickories, and other shade-tolerant hardwoods are released incrementally as the stand matures and the pines begin to die off. Under the natural fire regime of the past, this community phase is typically scattered in small patches across the landscape, usually in fire-protected microsites. However, as a result of ongoing exclusion of fire, these hardwood forests have continued to expand into areas once dominated by longleaf pine. As a consequence of canopy closure, fine fuels needed for low-intensity ground fires are absent, and a thick layer of leaf litter has accumulated on the forest floor.

Resilience management. Fire alone is not usually enough to transition this state back to the reference state. Restoration will usually require removal of undesirable hardwoods, planting of longleaf pine, together with the reintroduction of fire.

Dominant plant species

-

southern red oak (Quercus falcata), tree

-

post oak (Quercus stellata), tree

-

water oak (Quercus nigra), tree

-

Darlington oak (Quercus hemisphaerica), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

State 6

Managed Pine Plantation

This converted state is dominated by planted timber trees grown to produce a marketable wood product. Southern pines can be managed in a variety of different ways and for a variety of different purposes, including timber production, wildlife habitat, recreation, carbon sequestration, biomass production, pine straw production, silvopasture, or a combination of purposes. Pine plantations of the Sandhills region are primarily managed for pulpwood or higher value products such as saw and veneer logs or utility poles. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) and slash pine (P. elliottii) are the most commonly planted species in the region. Even-aged management is the most common timber management system. Ground cover is often ruderal in growth habit, usually including both native and non-native herbs.

Resilience management. Silviculture practices used in timber management include site preparation, prescribed fire, tree planting, weed control, fertilization, and thinning. Hardwood tree species will encroach after any thinning operation and are typically controlled with prescribed fire, herbicides, or a combination of both.

Alternative management prescriptions have been developed to allow for increased species diversity, especially in the herb layer, and improved wildlife habitat. Essentially these management prescriptions call for heavier thinning, more frequent prescribed fire, and planting of native grasses and forbs. Though not especially common, uneven-aged management can also be employed to better meet the dual objectives of wildlife habitat and timber production. In this system, the stand is never clear cut, as commercial thinning is staggered and conducted in conjunction with tree planting (where needed). Moreover, a proportion of the stand is allowed to reach a much greater age than is typically called for in even-aged management, sustaining a more complex canopy structure over longer periods. Natural regeneration rather than artificial is often used successfully in these systems (Brockway et al. 2005).

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

slash pine (Pinus elliottii), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

blueberry (Vaccinium), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

huckleberry (Gaylussacia), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

sugarcane (Saccharum), grass

-

longleaf woodoats (Chasmanthium sessiliflorum), grass

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

Community 6.1

Longleaf pine plantation

This community phase is characterized by planted longleaf pine which is managed for the primary purpose of timber production. In recent years, longleaf pine planting for marketable timber has increased. If managed appropriately, longleaf pine has the potential to return more profit than loblolly pine, thanks to its superior wood qualities, despite requiring a higher initial investment. Through improvements in planting and management, issues of slow growth rates and regeneration difficulty have largely been solved.

Longleaf has many unique wood properties and biological characteristics that make it economically competitive with other timber species despite its slow initial growth. Longleaf pine naturally grows straighter, tapers less, and produces a stronger, denser wood than loblolly pine. The superior wood quality brings top dollar for poles, pilings, and high-grade sawtimber. Longleaf is longer-lived than other southern pines and its long needles are preferred landscape mulch. With proper management, it is resistant to disease, insect injury, and wind damage from hurricanes. Management often includes prescribed fire and periodic stand thinning.

Though longleaf pine has been increasingly planted for timber production, not all tree planting is accompanied by native ground cover restoration. In the case of having non-native ground cover, the ecological functionality of the ecosystem does not mirror that of a intact longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem (NC Forest Service 2011).

Dominant plant species

-

longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

sugarcane (Saccharum), grass

-

slender woodoats (Chasmanthium laxum), grass

-

longleaf woodoats (Chasmanthium sessiliflorum), grass

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

Community 6.2

Loblolly or slash pine plantation

This converted state is dominated by rapidly-maturing pine species, the most common of which include loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) and slash pine (P. elliottii). The most common timber management system in pine plantations of this type is even-aged management, which ultimately calls for clear-cutting and re-planting at the end of a specified rotation age.

Resilience management. Precommercial thinning may occur as early as 5-10 years after stand establishment. Commercial thinning may occur at approximately 10 year intervals, usually for the purpose pulpwood. Pine plantations generally undergo a final harvest between 25 and 45 years of age, but shorter rotations of 15 to 18 years may also be considered.

Dominant plant species

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

slash pine (Pinus elliottii), tree

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), tree

-

sassafras (Sassafras albidum), tree

-

blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

small black blueberry (Vaccinium tenellum), shrub

-

dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa), shrub

-

farkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), shrub

-

St. Johnswort (Hypericum), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

rosette grass (Dichanthelium), grass

-

bluestem (Andropogon), grass

-

sugarcane (Saccharum), grass

-

slender woodoats (Chasmanthium laxum), grass

-

longleaf woodoats (Chasmanthium sessiliflorum), grass

-

sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), other herbaceous

-

striped prince's pine (Chimaphila maculata), other herbaceous

-

thoroughwort (Eupatorium), other herbaceous

-

aster (Symphyotrichum), other herbaceous

Pathway P

Community 6.1 to 6.2

Pathway P

Community 6.2 to 6.1

State 7

Old Field

This state develops in the immediate aftermath of agricultural abandonment, clear-cut logging, or other large-scale disturbances that lead to canopy removal. Which species colonize a particular location in the wake of a disturbance does involve a considerable degree of chance. It also depends a great deal on the type, duration, and magnitude of the disturbance event.

Community 7.1

Early successional, herbaceous

Dominant plant species

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

crabgrass (Digitaria), grass

-

sugarcane (Saccharum), grass

-

lovegrass (Eragrostis), grass

-

yankeeweed (Eupatorium compositifolium), other herbaceous

-

Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis), other herbaceous

-

rice button aster (Symphyotrichum dumosum), other herbaceous

-

Walter's aster (Symphyotrichum walteri), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

American burnweed (Erechtites hieraciifolius), other herbaceous

-

dwarf cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis), other herbaceous

-

Virginia dwarfdandelion (Krigia virginica), other herbaceous

-

juniper leaf (Polypremum procumbens), other herbaceous

-

cudweed (Pseudognaphalium), other herbaceous

Community 7.2

Shrub-dominated

This successional phase is dominated by shrubs and vines, along with seedlings of opportunistic hardwoods and pines.

Dominant plant species

-

sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree

-

silktree (Albizia julibrissin), tree

-

Chickasaw plum (Prunus angustifolia), tree

-

black cherry (Prunus serotina), tree

-

Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), tree

-

loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), tree

-

Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), tree

-

blackberry (Rubus), shrub

-

winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), shrub

-

greenbrier (Smilax), shrub

-

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), shrub

-

eastern baccharis (Baccharis halimifolia), shrub

-

evening trumpetflower (Gelsemium sempervirens), shrub

-

muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), shrub

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), grass

-

yankeeweed (Eupatorium compositifolium), other herbaceous

Pathway 8.1A

Community 7.1 to 7.2

The early successional, herbaceous phase naturally moves towards the shrub-dominated phase through natural succession.

Pathway 8.2A

Community 7.2 to 7.1

The shrub-dominated successional phase can return to the early successional, herbaceous phase through brush management, including herbicide application, mechanical removal, prescribed grazing, or fire.

State 8

Pastureland

This converted state is dominated by herbaceous forage species. Bermudagrass and bahiagrass are the most commonly planted forage grasses in the Sandhills region.

Agricultural yield information is available through Web Soil Survey (WSS) and can accessed here: http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/HomePage.htm

Dominant plant species

-

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), grass

-

bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum), grass

-

dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum), grass

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), grass

-

Italian ryegrass (Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), grass

-

crabgrass (Digitaria), grass

-

white clover (Trifolium repens), other herbaceous

-

vetch (Vicia), other herbaceous

-

plantain (Plantago), other herbaceous

-

buttercup (Ranunculus), other herbaceous

State 9

Cropland

This converted state produces food or fiber for human uses. It is dominated by domesticated crop species, along with typical weedy invaders of cropland.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 3

The reference state can transition to the degraded longleaf pine-oak woodland through fire suppression. Continued exclusion of fire, or an increase in the fire return interval (> 5 years), will lead to a transition from state 1 to state 3, characterized by increased hardwood and shrub development.

Constraints to recovery. As they mature, hardwood trees and shrubs that establish in the understory become more fire-tolerant as basal diameters increase. Inadequate fire allows for a thick layer of leaf litter to accumulate, which inhibits the recruitment of longleaf pine. Lack of longleaf regeneration further enhances the success of hardwood species, resulting in continued succession toward hardwood dominance. Without persistent and costly management, a comprehensive restoration is difficult to achieve (Brockway and Outcalt 2000; Walker and Silletti 2006).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 6

Though not common, it is possible to transition from the reference state to the managed pine plantation state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical debris/brush removal, 2) site preparation, and 3) planting of timber trees.

After timber harvest, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 7

Though not common, it is possible to transition from the reference state to the old field state, through clear-cut logging and abandonment.

Transition T1D

State 1 to 8

Though not common, it is possible to transition from the reference state to the pastureland state, through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, and 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T1E

State 1 to 9

Though not common, it is possible to transition the reference state to the cropland state, through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, 5) herbicide application, 6) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

The planted longleaf pine woodland state can be restored to the reference state through natural succession. This will require very long-term management (century-scale) in order to establish an uneven-aged stand.

Context dependence. Restoration is dependent on the long-term maintenance of a 2 to 5 year fire return interval.

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The planted longleaf pine woodland state can transition to the degraded longleaf pine-oak woodland through fire suppression. Continued exclusion of fire, or an increase in the fire return interval (> 5 years), will lead to a transition from state 2 to state 3, characterized by increased hardwood and shrub development.

Constraints to recovery. As they mature, hardwood trees and shrubs that establish in the understory become more fire-tolerant as basal diameters increase. Inadequate fire allows for a thick layer of leaf litter to accumulate, which inhibits the recruitment of longleaf pine. Lack of longleaf regeneration further enhances the success of hardwood species, resulting in continued succession toward hardwood dominance. Without persistent and costly management, a comprehensive restoration is difficult to achieve (Brockway and Outcalt 2000; Walker and Silletti 2006).

Transition T2B

State 2 to 7

Though not common, it is possible to transition from the reference state to the old field state, through clear-cutting and abandonment.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 8

Though not common, it is possible to transition the planted longleaf pine woodland state to the pastureland state, through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, and 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T2D

State 2 to 9

Though not common, it is possible to transition the planted longleaf pine woodland state to the cropland state, through 1) clear-cut logging, mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) herbicide application, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

The degraded longleaf pine woodland state can be restored to the reference state through thinning (hardwood, brush, and unwanted pine removal) and an increase in fire frequency (2-3 year return interval).

Context dependence. Care should be exercised when reintroducing fire to longleaf pine stands in this condition, as ladder fuels can lead to catastrophic canopy fires. Longleaf woodlands can accumulate large quantities of leaf litter with fire suppression, as needles are long and resistant to decay. High residual fuel loads can be problematic in fire-suppressed stands as a result. Fuel treatments such as raking and/or wetting the area around existing trees, or mowing to remove standing fuels, can be helpful in preventing tree mortality. Pine roots will readily grow into the litter layer in the absence of fire and trees may be killed when the litter is burned off. Further, if ladder fuels are present in sufficient quantities, care should be taken to prevent catastrophic canopy fires, which can occur when unusually hot fires climb into the canopy. If fire has been excluded for long enough that this is a concern, mechanical mastication can be used as a preventative measure. This procedure involves chipping or breaking apart fuels, creating a gap between surface fuels and canopy fuels (Brockway and Outcalt 2000; Walker and Silletti 2006; Kreye et al. 2016).

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

The degraded longleaf pine-oak woodland state can transition to the mixed pine-hardwood state through fire suppression. Continued exclusion of fire, or an increase in the fire return interval, can result in significant changes in species composition and vegetation structure, as encroaching hardwoods outcompete the remaining longleaf pine.

Transition T3B

State 3 to 6

Though not common, the degraded longleaf pine - oak woodland state can be transitioned to the managed pine plantation state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical debris/brush removal, 2) site preparation, and 3) planting of timber trees.

After timber harvest, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

Transition T3C

State 3 to 7

Though not common, it is possible to transition from this state to the old field state, through clear-cutting and abandonment.

Transition T3D

State 3 to 8

Though not common, it is possible to transition the degraded longleaf pine - oak woodland state to the pastureland state, through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, and 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, warm-season prescribed fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T3E

State 3 to 9

Though not common, it is possible to transition the degraded longleaf pine - oak woodland state to the cropland state, through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, and 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to cropland. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Weedy grasses and forbs can also be problematic on these lands.

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 2

The mixed pine-hardwood state can be transitioned to the planted longleaf pine woodland through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) site preparation, 3) tree planting, and 4) establishment of native groundcover if needed. Alternatively, if sufficient mature longleaf specimens are present, rehabilitation through selective thinning of hardwoods and unwanted pines (loblolly, slash) may be attempted if deemed feasible. This pathway relies on natural regeneration from mature seed trees to regenerate the stand rather than planting. In either case, the fire regime should be restored to 2-3 year frequency.

After tree and brush removal, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. The site should also be monitored for the emergence of native grasses and forbs in the understory. If herbaceous species do not regenerate naturally, the seed source may have been lost and will need to be reintroduced. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 3

The mixed pine-hardwood forest state can transition to the degraded longleaf pine-oak woodland through mechanical or chemical removal of hardwoods and unwanted pines (loblolly, slash), planting longleaf pine if necessary, and reintroduction of fire of at least 5 to 6 year return interval.

Context dependence. If desired longleaf pine trees are still present on the site, care should be exercised when reintroducing fire. Longleaf woodlands can accumulate large quantities of leaf litter with fire suppression, as needles are long and resistant to decay. High residual fuel loads can be problematic in fire-suppressed stands as a result. Fuel treatments such as raking and/or wetting the area around existing trees, or mowing to remove standing fuels, can be helpful in preventing tree mortality. Pine roots will readily grow into the litter layer in the absence of fire and trees may be killed when the litter is burned off. Further, if ladder fuels are present in sufficient quantities, care should be taken to prevent catastrophic canopy fires, which can occur when unusually hot fires climb into the canopy. If fire has been excluded for long enough that this is a concern, mechanical mastication can be used as a preventative measure. This procedure involves chipping or breaking apart fuels, creating a gap between surface fuels and canopy fuels.

The site should also be monitored for the emergence of native grasses and forbs in the understory. If herbaceous species do not naturally regenerate, the seed source may have been lost and will need to be reintroduced (Brockway and Outcalt 2000; Walker and Silletti 2006; Kreye et al. 2016).

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation |

|

| Tree/Shrub Establishment |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

Transition T4A

State 4 to 5

The mixed pine-hardwood forest state can transition to the mixed hardwood forest state through fire suppression. Continued exclusion of fire, or an increase in the fire return interval, results in further shifts in species composition and vegetation structure, ultimately resulting in a reduction of herbaceous species in the understory and the accumulation of leaf litter and woody debris on the forest floor. Over years of fire suppression, these changes have often progressed to such a degree that conditions are no longer conducive to the spread of fire, a phenomenon known as mesophication. In this scenario, when fire is removed for long periods of time, positive feedbacks result in succession toward forest systems that are less apt to burn. If fire suppression continues, it can result in the inability of the system to carry low-intensity fire. When fire does occur, it can have catastrophic results, as accumulated brush and woody debris in the understory can serve as fuel for more destructive fires.

Transition T4B

State 4 to 6

The mixed pine - hardwood forest state can be transitioned to the managed pine plantation state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical debris/brush removal, 2) site preparation, and 3) planting of timber trees.

After timber harvest, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

Transition T4C

State 4 to 7

The mixed pine-hardwood forest state can transition to the old field state through clear-cutting and abandonment.

Transition T4D

State 4 to 8

The mixed pine-hardwood forest state can transition to the pastureland state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T4E

State 4 to 9

The mixed hardwood forest state can transition to the cropland state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, 5) herbicide application, 6) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Restoration pathway R5A

State 5 to 2

The mixed hardwood forest state can be restored to the planted longleaf pine woodland state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) site preparation, 3) tree planting, and 4) establishment of native groundcover.

After tree and brush removal, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation.

Restoration pathway R5B

State 5 to 4

The mixed hardwood forest state can transition to the mixed pine-hardwood forest state through selective thinning of hardwoods, establishment of pines if necessary, and reintroduction of a 3-5 year fire return interval. Hardwoods can be removed through either mechanical or chemical means.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation |

|

| Tree/Shrub Establishment |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

Transition T5A

State 5 to 6

The mixed hardwood forest state can be transitioned to the managed pine plantation state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical debris/brush removal, 2) site preparation, and 3) planting of timber trees.

After timber harvest, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

Transition T5B

State 5 to 7

The mixed hardwood forest state can transition to the old field state through clear-cutting and abandonment.

Transition T5C

State 5 to 8

The mixed hardwood forest state can transition to the pastureland state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, and 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Herbicide applications, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning treed land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody plants are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T5D

State 5 to 9

The mixed hardwood forest state can transition to the cropland state through 1) clear-cut logging, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) applications of fertilizer/lime, 5) herbicide application, 6) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Transition T6A

State 6 to 4

Though not common, the managed pine plantation state can transition to the mixed pine-hardwood forest state through abandonment of forestry practices without harvesting the remaining trees on the site. Due to lack of thinning, the growth rate of planted pines is significantly reduced as encroaching hardwoods compete with pines for resources.

Transition T6B

State 6 to 7

The mixed pine-hardwood forest state can transition to the old field state through clear-cutting and abandonment.

Transition T6C

State 6 to 8

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the pastureland state through 1) timber harvest, 2) mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 3) seedbed preparation, 4) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. Applications of fertilizer and lime can be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T6D

State 6 to 9

The managed pine plantation state can transition to the cropland state through 1) Timber harvest, mechanical brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) herbicide application, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Restoration pathway R7A

State 7 to 2

The old field state can be transitioned to the planted longleaf pine woodland state through 1) clearing (mechanical or chemical brush removal), 2) site preparation, and 3) tree planting.

After clearing, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Firebreak |

|

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation |

|

| Tree/Shrub Establishment |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

Transition T7A

State 7 to 4

Context dependence. This transition pathway occurs in the absence of fire and without an adequate seed source for longleaf pine.

Transition T7B

State 7 to 6

The old field state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through 1) clearing (mechanical or chemical brush removal), 2) site preparation, and 3) planting of timber trees.

After clearing, site preparation should occur. Coarse woody debris can impede tree planters. Concentrating debris in windrows or piles and burning it is recommended. Unwanted vegetation should be controlled prior to planting to reduce competition for the new stand. This can be accomplished by mechanical and/or chemical methods. Selective herbicides can be used to target specific species or groups of unwanted vegetation. A professional forester should be consulted prior to this undertaking to better meet landowner management objectives.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Firebreak |

|

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation |

|

| Tree/Shrub Establishment |

|

Transition T7C

State 7 to 8

The old field state can transition to the pastureland state through through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, and 3) planting of perennial grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. A broad spectrum herbicide, fire, and/or root-raking can be helpful in transitioning wooded or semi-wooded land to pasture. This is done in part to limit coppicing, as many woody pioneers are capable of sprouting from residual plant structures left behind after clearing. Judicious use of root-raking is recommended, as this practice can have long-term repercussions with regard to soil structure. Applications of fertilizer and lime can also be helpful in establishing perennial forage species. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.

Transition T7D

State 7 to 9

The old field state can transition to the cropland state through 1) mechanical tree/brush/stump/debris removal, 2) seedbed preparation, 3) applications of fertilizer/lime, 4) weed control, 5) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Restoration pathway R8A

State 8 to 2

The pastureland state can be restored to the planted longleaf pine woodland state through 1) site preparation, 2) weed control, 3) tree planting, and 4) establishment of native groundcover. This restoration pathway will benefit from a preliminary assessment of local soil and site conditions, so that management strategies can be tailored to the needs of the site. A basic soil test may be a worthwhile investment. Many pastures have received applications of lime, which can dramatically increase the pH of the soil over time. It is difficult to successfully establish longleaf pine on sites with a pH higher than 7.0. If needed, applications of elemental sulfur can be used to lower the pH.

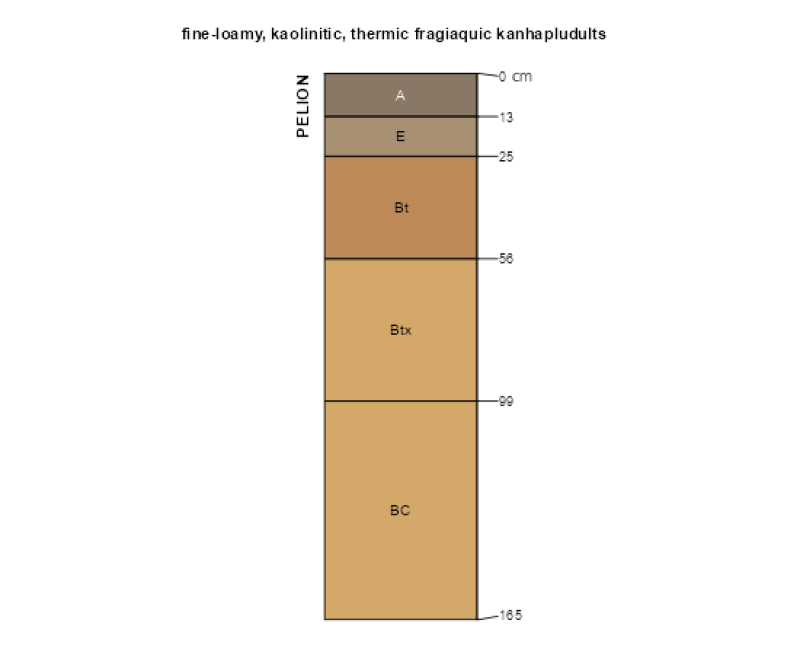

When planting longleaf pine on former pastures, some form of weed control will be usually be necessary to discourage competition with non-native sod-forming forage grasses. Aggressive control of these herbaceous species can be achieved using appropriate herbicides. A technique known as scalping has also proved to be beneficial on some pastures. Scalping essentially forms a shallow (2-4”) but wide (30-36”) furrow by peeling back and removing the upper few inches of sod. However, some caution is advised when considering this technique. Scalping is not recommended in wet areas or on soils with high clay content because the scalped rows may hold too much water and drown the seedlings. In contrast to most other soils of the Sandhills region, water movement through the profile is slow in soils associated with this ecological site. Some soils have a high clay content in the subsoil, while others have a naturally cemented subsurface layer that holds up water. Judicious use of scalping is recommended.

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Firebreak |

|

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation |

|

| Tree/Shrub Establishment |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

Transition T8A

State 8 to 6

The pastureland state can be transitioned to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation, weed control, and tree planting.

When planting southern pines on former pastures, some form of weed control will be usually be necessary to discourage competition with non-native sod-forming forage grasses. Aggressive control of these herbaceous species can be achieved using appropriate herbicides. A technique known as scalping has also proved to be beneficial on some pastures. Scalping essentially forms a shallow (2-4”) but wide (30-36”) furrow by peeling back and removing the upper few inches of sod. However, some caution is advised when considering this technique. Scalping is not recommended in wet areas or on soils with high clay content because the scalped rows may hold too much water and drown the seedlings. In contrast to most other soils of the Sandhills region, water movement through the profile is slow in soils associated with this ecological site. Some soils have a high clay content in the subsoil, while others have a naturally cemented subsurface layer that holds up water. Judicious use of scalping is recommended.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Firebreak |

|

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation |

|

| Restoration and Management of Rare and Declining Habitats |

|

| Forest Stand Improvement |

|

| Transition from Irrigation to Dry-land Plan - Applied |

|

Transition T8B

State 8 to 7

The pastureland state can transition to the old field state through cessation of grazing and abandonment.

Transition T8C

State 8 to 9

The pastureland state can transition to the cropland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) applications of fertilizer/lime, 3) herbicide application, and 4) planting of crop or cover crop seed.

Restoration pathway R9A

State 9 to 2

The cropland state can be transitioned to the planted longleaf pine woodland state through 1) site preparation, 2) weed control, 3) tree planting, and 4) establishment of native groundcover. This restoration pathway will benefit from a preliminary assessment of local soil and site conditions, so that management strategies can be tailored to the needs of the site. A basic soil test may be a worthwhile investment. Most agricultural fields have received regular applications of lime, which can dramatically increase the pH of the soil over time. It is difficult to successfully establish longleaf pine on sites with a pH higher than 7.0. If needed, applications of elemental sulfur can be used to lower the pH.

When planting longleaf pine on former cropland, some form of weed control will be usually be necessary to discourage competition with common agricultural weeds. Aggressive control of these herbaceous species can be achieved using appropriate herbicides. A technique known as scalping has also proved to be beneficial in some cases. Scalping essentially forms a shallow (2-4”) but wide (30-36”) furrow by peeling back and removing the upper few inches of sod. However, some caution is advised when considering this technique. Scalping is not recommended in wet areas or on soils with high clay content because the scalped rows may hold too much water and drown the seedlings. In contrast to most other soils of the Sandhills region, water movement through the profile is slow in soils associated with this ecological site. Some soils have a high clay content in the subsoil, while others have a naturally cemented subsurface layer that holds up water. Judicious use of scalping is recommended.

On some sites, cropland may benefit from subsoiling prior to planting, as many soils of the region can develop a plow pan with cultivation. These conditions will inhibit seedling establishment.

Transition T9A

State 9 to 6

The cropland state can transition to the managed pine plantation state through site preparation, weed control, and tree planting.

When planting southern pines on former cropland, some form of weed control will be usually be necessary to discourage competition with common agricultural weeds. Aggressive control of these herbaceous species can be achieved using appropriate herbicides. A technique known as scalping has also proved to be beneficial in some cases. Scalping essentially forms a shallow (2-4”) but wide (30-36”) furrow by peeling back and removing the upper few inches of sod. However, some caution is advised when considering this technique. Scalping is not recommended in wet areas or on soils with high clay content because the scalped rows may hold too much water and drown the seedlings. In contrast to most other soils of the Sandhills region, water movement through the profile is slow in soils associated with this ecological site. Some soils have a high clay content in the subsoil, while others have a naturally cemented subsurface layer that holds up water. Judicious use of scalping is recommended.

On some sites, cropland may benefit from subsoiling prior to planting, as many soils of the region can develop a plow pan with cultivation. These conditions will inhibit seedling establishment.

Transition T9B

State 9 to 7

The cropland state can transition to the old field state through agricultural abandonment.

Transition T9C

State 9 to 8

The cropland state can transition to the pastureland state through 1) seedbed preparation, 2) weed control, and 3) planting of perennial forage grasses and forbs.

Context dependence. To convert cropland to pastureland, weed control and good seed-soil contact are important. It is also critical to review the labels of herbicides used for weed control and on the previous crop. Many herbicides have plant-back restrictions, which if not followed could carryover and kill forage seedlings as they germinate. Grazing should be deferred until grasses and forbs are well established.