Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F131AY210AR

St. Francis - Old Moderately Wet Natural Levee and Meander Scroll Forest

Last updated: 6/10/2025

Accessed: 10/19/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 131A–Southern Mississippi River Alluvium

The Southern Mississippi River Alluvium (MLRA 131A) is the largest of 4 MLRAs within Land Resource Region O, the Mississippi Delta Cotton and Feed Grains Region. It occurs in portions of 7 states including Louisiana (32 percent), Arkansas (26 percent), Mississippi (26 percent), Missouri (12 percent), Tennessee (3 percent), Kentucky (1 percent), and Illinois (less than 1 percent). The MLRA is comprised of 29,555 square miles and extends roughly 650 miles from an area near Cape Girardeau, Missouri in the north to the MLRA’s transition to the Gulf Coast Marsh (MLRA 151) in the south. Average elevations range from 330 feet in the north to sea level in the southern part of the area. For much of the north-south distance, the MLRA is bounded to the east by an abrupt rise in elevation of loess-capped bluffs and hills, the Southern Mississippi Valley Loess (MLRA 134). West of the Mississippi River, the boundary is less distinct except to the northwest where the MLRA abuts the Ozark Plateaus and Ouachita province (MLRAs 116A, 117, and 118A). South of the Ozark and Ouachita escarpment, the MLRA adjoins the Southern Mississippi River Terraces (MLRA 131D), which includes the fabled Grand Prairie and merges with the valleys of the Arkansas and Ouachita rivers (MLRA 131B) and the Red River (MLRA 131C). Occurring within or bordering the Southern Mississippi River Alluvium are three separate loess-capped, upland remnants: Crowley’s Ridge, Macon Ridge, and Lafayette Loess Plain, which are western units of MLRA 134 (USDA-NRCS, 2006a).

MLRA 131A is characterized by landscapes that were created and influenced by the current and earlier paths of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Waters transporting the materials that formed the area originate from as far west as the east slope of the Continental Divide to the western edge of the Appalachian Divide in the east. This comprises a drainage basin of roughly 1,245,000 square miles and includes all or parts of thirty-one U.S. states and two Canadian provinces (Elliott, 1932). The drainage basin of the Mississippi River roughly resembles a funnel, which has its spout at the Gulf of America. Waters from as far east as New York and as far west as Montana contribute to flows in the lower extent of the river (USACE, 2017). The soils of these alluvial landscapes are very deep, dominantly poorly and somewhat poorly drained, and have textures that are mostly loamy or clayey. Principal soil orders are Alfisols, Vertisols, Inceptisols, and Entisols (USDA-NRCS, 2006a).

The fluvial processes that shaped the area were highly dynamic, diverse, and complex. During the Pleistocene epoch, multiple continental glacial-interglacial cycles resulted in extreme fluctuations in river discharge and sediment loads. A braided river regime characterized the fluvial dynamics of the Mississippi River through much of the last glacial cycle (Autin et al., 1991; Rittenhour et al., 2007). Rapid aggradation of glacial outwash led to the development of prominent valley train features over a large portion of the area (Autin et al., 1991; Saucier, 1994; Aslan and Autin, 1999; Blum et al., 2000; Rittenour et al., 2007). A changing climate, meltwater withdrawal, and sea-level change induced a transition from a braided river regime to a predominantly single-channeled, laterally migrating river system during the Holocene epoch (Rittenhour et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2012) – characteristics that continue today. Fluvial dynamics of the migrating river resulted in the development of broad meander belts, backswamp environments, and extensive deltaic complexes (Saucier, 1994; Klimas et al., 2011a).

Tremendous expanses of bottomland hardwood forests once covered much of the area. Today, the land base is largely in agriculture production, and soybeans, cotton, corn, and rice are the principal crops with sugarcane rising in importance in the southernmost portion of the MLRA (USDA-NRCS, 2022).

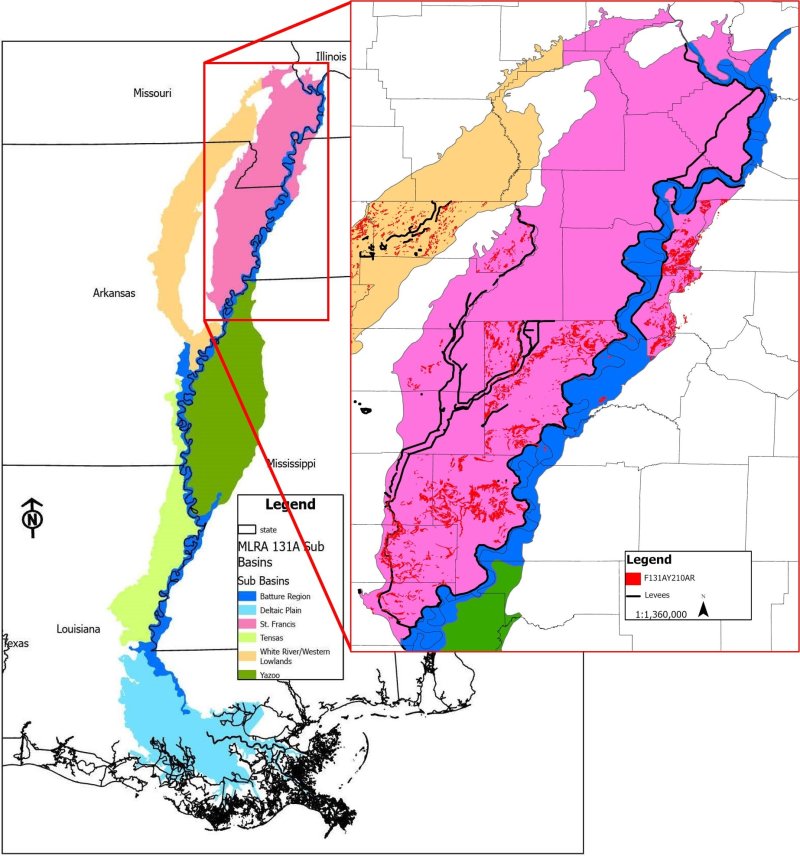

Due to its size and biophysical variability, the Technical Team advised subdividing the MLRA into six subregions: Western Lowlands, St. Francis Basin, Yazoo Basin, Tensas Basin, Delta Plain, and Batture.

LRU notes

There are no agency-approved and established Land Resource Units (LRUs) for MLRA 131A. However, the characteristics of each of the six subregions in this MLRA warrant noting and are presented here for each associated ecological site. This provisional ecological site is broadly mapped within the St. Francis Basin.

The St. Francis Basin is geographically positioned in northeastern Arkansas and southeastern Missouri where it, in addition to the Batture and Western Lowlands, form the northern terminus of MLRA 131A. For convenience and ease of administering the Ecological Site Inventory, small portions of the MLRA occurring east of the Mississippi River in extreme western Tennessee and Kentucky are collectively grouped with the basin’s extent in Arkansas and Missouri. The following characterization includes the combined area.

The MLRA boundary of the basin extends some 190 miles (north to south) from Cape Girardeau, Missouri to the vicinity of Helena, Arkansas. For much of its north-south distance, its width (east to west) is approximately 40 miles but narrows considerably south of Memphis, TN. The basin is bounded to the west by Crowley’s Ridge and to the east by the most recent meander belt of the Mississippi River. Elevations range from about 340 feet in the north to around 175 feet in the south (Saucier, 1994). St. Francis Basin includes portions of: Lee, St. Francis, Crittendon, Cross, Poinsett, and Mississippi counties of Arkansas; Pemiscot, Dunkin, New Madrid, and Mississippi counties of Missouri; Lake, Dyer, and Lauderdale counties of Tennessee. Major towns include: West Memphis, Marked Tree, Trumann, Blytheville, Paragould, Piggott, and Black Oak, Arkansas; Caruthersville, Hayti, Portageville, Kennett, Charleston, Sikeston, and Cape Girardeau, Missouri; and Tiptonville, Tennessee. Major highways include: Interstate 55, Interstate 40, U.S. Highway 61, U.S. Highway 63, U.S. Highway 64, U.S. Highway 78, and TN Highway 103.

The geomorphology of the basin is exceedingly complex – manifestations of incredible hydrogeologic and geologic forces. The most significant of these forces for the Mississippi River Valley was serving as a sluiceway through which huge quantities of glacial meltwater and outwash were funneled during multiple continental glaciations. The northwestern two thirds of the basin is mainly comprised of Late Pleistocene (ca. 11,700 to 129,000 years B.P.; chronology after Head, 2019) glacial outwash materials. Large landscapes or “basin subareas” were created or influenced by tremendous amounts of outwash material that, episodically, were released during catastrophic outburst floods of enormous magnitude (Saucier, 1994). Fluvial dynamics of these events resulted in braided river regimes of both the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Examples of large landscapes that were shaped and reshaped by these fluvial processes and episodes include Sikeston Ridge, Charleston Fan, Morehouse Lowland, and Malden Plain (Stevens and Krusekopf, 2020). Major geomorphic features created in the wake of these forces include prominent sandy ridges; broad, braided-stream terraces (valley trains) at varying elevations or levels; and eolian environments of sand dune fields east of Sikeston Ridge (Saucier, 1994).

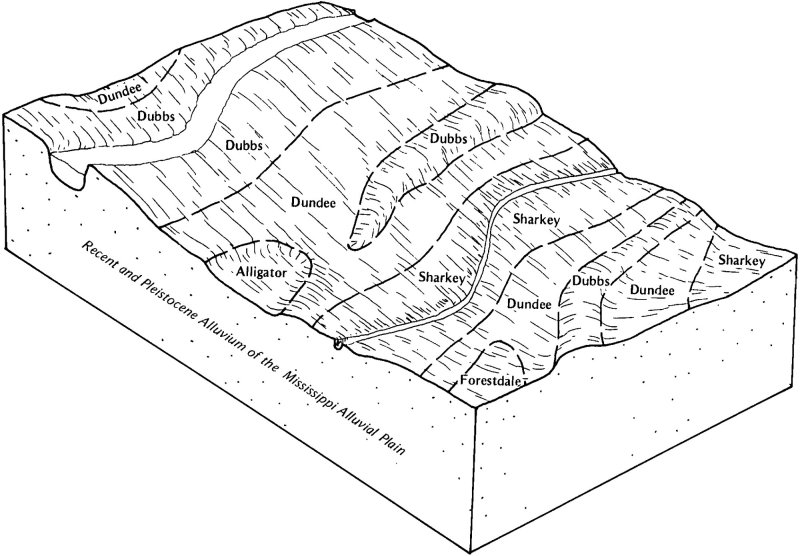

A changing climate, meltwater withdrawal, and sea-level change induced a transition from a braided river regime to a predominantly single-channeled, laterally migrating river system during the Holocene epoch (ca. 11,700 years B.P. to present; epoch chronology after Head, 2019) (Rittenour et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2012). Landscapes across the southeastern third of the St. Francis Basin are mainly comprised of former paths of the Mississippi River and its associated alluvial environment of sinuous meander belts. Major landforms comprising the meander belt environment include natural levees, point bar deposits (meander scrolls) and abandoned channels (oxbow lakes) and courses. The higher elevations of natural levees and point bars form an alluvial ridge, which often directs local drainage and floodwaters to the intervening flood basins or backswamps (Saucier, 1994).

In addition to hydrologic influences, the basin’s landscapes are subject to geologic forces. In 1811-1812, four of the largest earthquakes to hit eastern North America occurred in an area that encompassed extreme northeastern Arkansas, southeastern Missouri, and northwestern Tennessee. This area is known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone, which is named after a small settlement near the epicenter of one of the earthquakes (Saucier, 1994). Reports of the New Madrid earthquakes included widespread bank caving, reversal of river flow, landslides, earth waves, forest destruction, land uplifts, and land sinking. A few of the notable land areas or features attributed to or influenced by the seismic events include the St. Francis Sunken Lands, Tiptonville Dome, Ridgely Ridge, Reelfoot Lake, and massive landslides occurring along the adjoining Loess Bluffs of MLRA 134 (Fuller, 1912; Saucier, 1994). Perhaps the most dramatic geomorphic effects were the land fissuring and sand blows resulting from liquefaction (Saucier, 1994). According to Castilla and Audemard (2007), these are “…the largest ever-reported isolated sand blows.” Saucier (1994) emphasized that there are millions of liquefaction features from the earthquakes that are distributed over a 4,000 square mile area.

The movement of water through the basin is influenced by the complex sequence of remnant braided outwash channels, overflow channels, distributaries, and former channels and courses of the Mississippi River. Many of these features convey smaller modern streams within them. Principal streams of the basin are its namesake, the St. Francis River in addition to Little River, Tyronza River, and Pemiscot Bayou. Historically, large floods on the Mississippi River and in the St. Francis tributary system and greater basin led to frequent flooding, inundating landscapes of low relief for very long durations (Moore, 1972). To lessen the severity of flooding, the St. Francis Basin underwent a coordinated and comprehensive flood control and drainage effort. Extensive modification of the basin’s natural hydrology included hundreds of miles of constructed levees along the mainstem of the Mississippi River and basin tributaries; channel modifications on many streams; constructed floodways; water control structures; land leveled areas; and an extensive network of surface drainage systems (Klimas et al., 2013). The extensive modifications to the basin’s hydrology coupled with increased access set the stage for broadscale conversion of former forestland to a variety of land uses with agriculture production being dominant.

All ecological sites in the St. Francis Basin are bounded by the extensive constructed levee system along the Mississippi River. The constructed levee occurs on both sides (i.e., east and west) of the active river channel. The areas protected by levees east of the Mississippi River include portions of Lake, Obion, Dyer, and northern Lauderdale counties in Tennessee and the western extent of Fulton County, Kentucky. (Soils mapped in southern Illinois’s portion of MLRA 131A mostly have a mesic soil temperature regime and do not correlate to this ecological site.) All lands between the river channel and the constructed levee (or Loess Hills where levees are absent) are referred to as the Batture, and that subregion encapsulates its own complement of ecological sites due to significantly different hydrologic regimes (Smith and Klimas, 2002).

Classification relationships

All or portions of the geographic range of this site fall within several ecological and land classifications including:

- NRCS Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 131A – Southern Mississippi River Alluvium (USDA-NRCS, 2006a)

- National Hierarchical Framework of Ecological Units: 234 Lower Mississippi Riverine Forest Province; 234D White and Black River Alluvial Plains Section; 234Da North Mississippi River Alluvial Plain Subsection (Cleland et al., 2007)

- Environmental Protection Agency Level III Ecoregion: 8.5.2 Mississippi Alluvial Plain; Level IV Ecoregion: Northern Holocene Meander Belt, 73a; (Griffith et al., 1998; Chapman et al., 2002; Woods et al., 2002; Woods et al., 2004; Wiken et al., 2011)

- Mississippi River High Floodplain (Bottomland), CES203.196 (NatureServe, 2020)

- The following is the HGM Subclass, geomorphic setting, and PNV association that best correlates to this site in the St. Francis Basin (developed by Klimas et al., 2013): F4, Moderately drained lowlands, Sugarberry – Green Ash – American Elm

Ecological site concept

This site is generally associated with older meander belts (former channels) of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Here, the site occupies positions intermediate to the higher, better drained areas and the lower, wetter toeslopes of older natural levees and meander scroll ridges. Additionally, the soils of this site have been mapped along active tributaries to the Mississippi River, on low ridges and rises adjacent to backswamp areas. The soils are very deep, somewhat poorly drained that formed in thinly stratified beds of loamy alluvium. A key characteristic of these soils is the prominent profile development as determined by distinct argillic (clay) accumulations in the subsoil (B horizon). Slopes are typically 0 to 3 percent but may range up to 8 percent. Areas that have naturally recovered in forest often support a sugarberry (Celtis laevigata) – American elm (Ulmus americana) – green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) forest association or a variant of this type. Reportedly, species that are favored in management on these soils include Nuttall oak (Quercus texana), cherrybark oak (Q. pagoda), water oak (Q. nigra), willow oak (Q. phellos), swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii), sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), green ash, eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), and American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis). Additional species occasionally to frequently observed include red maple (Acer rubrum), red mulberry (Morus rubra), common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), and pecan (Carya illinoinensis). Of note, this site occurs on the protected side of the extensive Mississippi River levee system.

Associated sites

| F131AY209AR |

St. Francis - Old Loamy Natural Levee and Meander Scroll Forest This site occurs on slightly higher and drier positions than the adjoining F131AY210AR. These adjacent sites primarily occur on former Mississippi River meander belts and on natural levees of active Mississippi River tributaries. |

|---|---|

| F131AY211AR |

St. Francis - Old Wet Natural Levee and Meander Scroll Forest This site occurs on lower and wetter positions than the adjoining F131AY210AR. These adjacent sites primarily occur on former Mississippi River meander belts and on natural levees of active Mississippi River tributaries. |

Similar sites

| F131AY206AR |

St. Francis - Wet Braided Interfluve Forest This site consists of somewhat poorly drained soils on Late Pleistocene valley trains in the St. Francis Basin. A few of the same soil components (e.g., Dundee series) were mapped on both valley train and the Holocene meander belt landforms of F131AY210AR. These soil-site environments formed under different hydrologic regimes, landscape processes, and time periods. |

|---|---|

| F131AY107AR |

Western Lowlands - Moderately Wet Bottomland Riparian Forest This site consists of somewhat poorly drained soils on mid-slope positions of Holocene natural levees and riparian areas in the Western Lowlands. The location of this is generally along active stream systems, today. A few of the same soil components (e.g., Dundee series) were mapped on abandoned Mississippi River meander belt landforms of F131AY210AR. These soil-site environments formed under different hydrologic regimes, landscape processes, and time periods. |

| F131AY307MS |

Yazoo - Old Moderately Wet Natural Levee and Meander Scroll Ridge Forest This site occupies similar positions and has similar drainage characteristics as F131AY210AR. The principal difference is F131AY307MS is confined to the Yazoo Basin. |

| F131AY405LA |

Tensas Basin - Somewhat Poorly Drained Bottomland Hardwoods This site occupies similar positions and has similar drainage characteristics as F131AY210AR. The principal difference is that F131AY405LA is occurs within the Tensas Basin. |

| F131AY503LA |

Delta Plain - Somewhat Poorly Drained Bottomland Hardwoods This site occupies similar positions and has similar drainage characteristics as F131AY210AR. The principal difference is that F131AY503LA is confined to the Delta Plain. |

| F131AY110AR |

Western Lowlands - Old Moderately Wet Natural Levee and Braided Interfluve Forest This site primarily occurs on mid-slope positions of old natural levees and the higher interfluves of remnant glacial outwash channels on Pleistocene-age valley train terraces in the Western Lowlands. A few of the same soil components (e.g., Dundee series) were mapped on both valley train and the Holocene meander belt landforms of F131AY210AR. These soil-site environments formed under different hydrologic regimes, landscape processes, and time periods. |

Figure 1. Distribution of F131AY210AR.

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

States 1, 5 and 2 (additional transitions)

States 3 and 7 (additional transitions)

| T1A | - | Manipulate composition and manage for production (Community 2.1); Heavy timber cutting/high-grading (Community 2.2) |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); preparation for cultivation |

| T1C | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); seedbed preparation; establishment of desired forage; manage for grazing |

| T2A | - | Reestablish missing species; control exotics (mechanical/chemical); timber stand improvement; natural stand dynamics |

| T2B | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); preparation for cultivation |

| T2C | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); seedbed preparation; establishment of desired forage; manage for grazing |

| T3A | - | Precision land leveling |

| T3B | - | Establish desired forage species and manage for grazing. |

| T3C | - | Natural succession (Community 6.1) or site prep (plow pan breakup, fertilizing, etc.); planting species appropriate for site (Community 6.2) |

| T3D | - | Establish select native species suitable for site; prepare site for planting (herbicide and/or mechanical) |

| T5A | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); preparation for cultivation |

| T5B | - | Natural succession (Community 6.1) or site prep (plow pan breakup, fertilizing, etc.); planting species appropriate for site (Community 6.2) |

| T5C | - | Establish select native species suitable for site; prepare for planting (herbicide and/or mechanical) |

| T6A | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); preparation for cultivation |

| T6B | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); seedbed preparation; establishment of desired forage; manage for grazing |

| T7A | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); preparation for cultivation |

| T7B | - | Vegetation/stump removal (mechanical/chemical); seedbed preparation; establishment of desired forage; manage for grazing |

| T7C | - | Natural succession (Community 6.1) or site prep; planting species appropriate for site (Afforestation – Community 6.2). |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

| 2.1A | - | Cessation of management followed by heavy cutting/high-grading |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2A | - | Silvicultural treatments: removal of undesirable species; re-establish species favored in management; timber stand improvement; establish advance regeneration |

State 3 submodel, plant communities

| 3.1A | - | Soil disturbance (tillage); reduction of soil health. |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1B | - | Conventional tillage, seeding, and fertility management for crops. |

| 3.2A | - | No-till, cover crops, reduced till–soil health improvements. |

| 3.2B | - | Conventional tillage, seeding, and fertility management for crops. |

| 3.3A | - | Reduced till, no-till, and cover crops with soil health improvements as a goal. |

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

| 5.1A | - | Seeding and/or management for desired species composition. |

|---|---|---|

| 5.1B | - | Species management without overseeding. |

| 5.2A | - | Seeding, fertilizing, management/removal of undesirable species. |

| 5.2B | - | Species management without overseeding |

| 5.3A | - | Seeding, fertilizing, management/removal of undesirable species. |

| 5.3B | - | Seeding and/or management for desired species composition. |

| 5.3C | - | Lack of disturbance; no (infrequent) mowing, herbivory, or brush management; natural succession of woody species. |

| 5.4A | - | Brush management/removal of unwanted species. |

State 6 submodel, plant communities

| 6.1A | - | Remove undesirable competitors; final soil preparation; establish site-appropriate species (favored in management). |

|---|